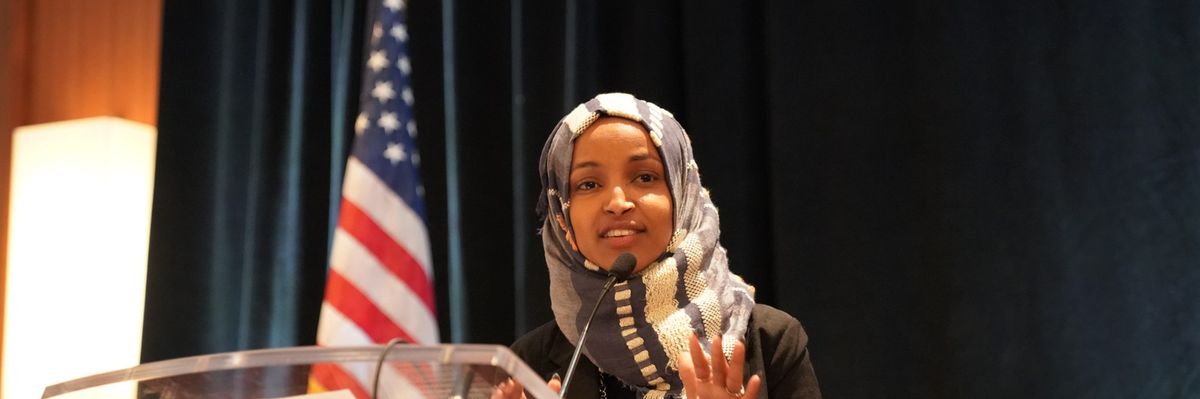

This week Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) introduced “The Global Human Rights and Humanitarian Accountability Act,” a bill that policy analysts, pundits, and legislators alike should applaud and support as a broad and bold assertion of congressional commitment to counter the most abhorrent and illegal actions of demagogues and dictators as they inflict various atrocities on their own populations.

This human rights bill is part of a multi-legislative proposal Rep. Omar has dubbed “A Pathway to Peace,” which includes other proposals calling for major budgetary reallocations for peacebuilding, significant changes in current U.S. policies regarding migration, protection of children and youth, and a commitment to U.S. adherence to the work of the International Criminal Court. A distinct part of this package is a rather focused set of criteria for the congressional oversight of the U.S. use of economic sanctions that are often imposed exclusively by the Executive branch — the President and the Treasury Department — under the 1977 International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA).

Rep. Omar’s legislation mandates that within 60 days after a president imposes sanctions under the IEEPA, Congress must approve the renewal of sanctions, or they come to an end. This will significantly improve current U.S. sanctions policy of “maximum pressure” that has become the economic equivalent of saturation bombing. More calibrated and smartly applied targeted U.S. sanctions are the tool most needed to end mass atrocities and improve human rights.

Thus, by also providing rules for imposing sanctions by the president and Congress, “The Global Human Rights and Humanitarian Accountability Act” works well in tandem with the bills in this package for peace. Notably, the human rights bill operationalizes the unique capacity of sanctions to derail massive atrocities at the earliest possible time. It does so by providing clear “red lines” for what constitutes such abuses, for example war crimes and genocide, thus reducing much of the political wrangling that often occurs within the U.S. government about such actions.

In its specification of the various and distinct actions perpetrated against the innocent under the three categories of Genocide, Crimes Against Humanity, and War Crimes, Rep. Omar’s bill provides clear definitional parameters regarding which behaviors of national leaders the entire U.S. government should ensure comes to an end as soon as it begins. Particularly helpful to policy makers trying to comprehend differences between generalized repression of a population and direct violations of law are the bill’s careful explanation of eleven distinct categories of violations of international humanitarian law, and its 35 distinct types of war crimes.

Once passed, the Act deepens the ability of Congress to keep its finger on the pulse of gross human rights violations in nations in transition from dictatorship, to investigate and name war crimes during internal and external violence conflict, and to expose the diversity of genocidal actions and perpetrated atrocities used by the world’s dictators to maintain their illegitimate power. A major component of congressional capacity outlined in this bill is the creation of the “United States Commission on Atrocity Accountability and Human Rights.” The Commission will include four members of the House and four Senators appointed in bi-partisan manner, a White House appointee and the U.S. Ambassador at Large for War Crimes. Its functions will include monitoring of atrocity-like violence, making policy recommendations to the president, Congress, and the secretary of state regarding which actors warrant sanctions, and issuing reports of its work.

The activities of the Commission and the actions empowered by this bill complements ongoing congressional work in the human rights and mass atrocities field that has unfolded in the important work done for years under the Lantos Commission. This bill also provides a robust companion to the Magnitsky Act. In fact, Rep. Omar’s bill has the potential to parallel the expansive nature of the Magnitsky Act, which originally focused on sanctioning Russian repressive behavior, but quickly became implemented globally as one of the best expressions of the U.S. human rights policy.

Rep. Omar’s bill authorizes the president to impose economic sanctions on a government that has been found to engage in any of these terrible violent actions specified in the bill. In so doing it demonstrates that the president and Congress can work in a coordinated fashion to take concentrated action for human rights and humanitarian protections as a core and ongoing concern for American national security. Moreover, the bill illustrates a more appropriate and effective use of the sanctions tool by the president in a policy area where sanctions have a good track record, the exceptions being when have been used too little and too late, as in the genocides in Rwanda and Darfur.

Based on the bill’s vision, and particularly the work of the Commission, Congress and president should embrace it fully. To appreciate its goals and potential they need only to think back nine years ago this month when the U.S., other nations, and the U.N. struggled with what actions to take to deal with Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, who had pledged to “crush the cockroaches” rebelling against him.

On the one hand, the targeted financial sanctions, asset freeze, travel ban, and arms embargo imposed by the United States, the European Union and the U.N. combined to cut off nearly half of Gaddafi’s usable monies — $36 billion in all. These sanctions immediately denied Gaddafi the funds to import heavy weapons, to hire foot soldier mercenaries, or to contract with elite commando units that were all to be aimed at civilian protesters. On the other hand, too narrow a policy vision and too much optimism about the use of NATO’s “preventive military bombing” actually expanded the violence significantly and led to a Libya engulfed by internal war ever since.

Taken in tandem with the other the bills Rep. Omar introduced this week, “The Global Human Rights and Humanitarian Accountability Act” puts a premium on early recognition of atrocities on the horizon and rapid, coordinated response by the president and Congress that imposes targeted sanctions to deprive a government of repressive resources. These measures include automatic withdrawal of U.S. security assistance, arms sales, and security training that often enable governments to commit atrocities. In this way, the Act provides a much needed framework for advancing American values of human rights and stifling violence against innocence in a manner that does not require the use of military force.