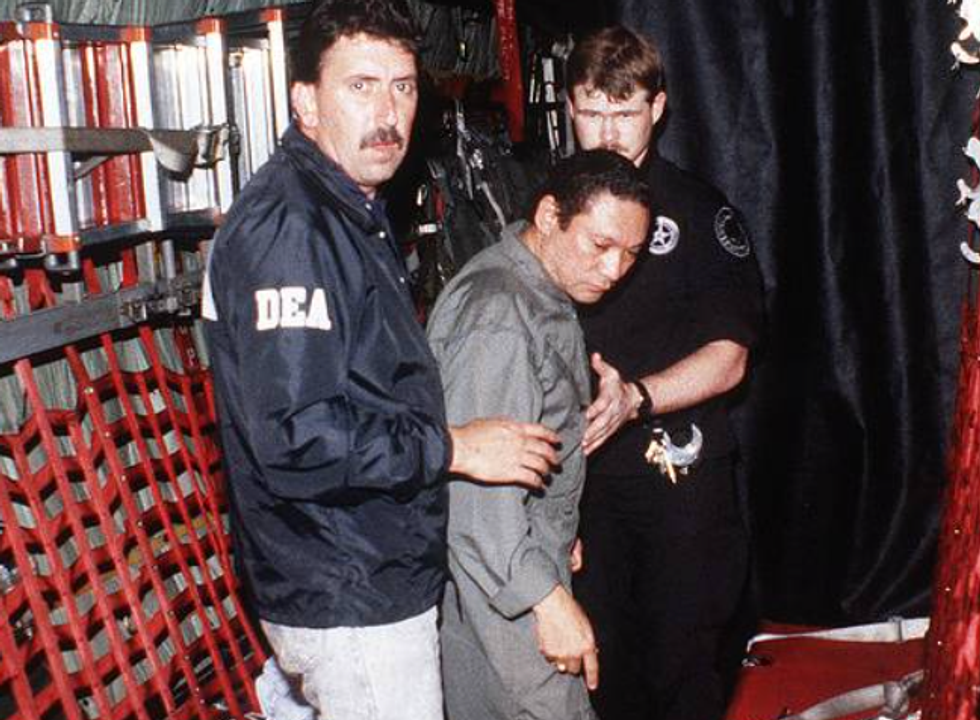

On Dec. 20, 1989, the U.S. military launched “Operation Just Cause” in Panama. The target: dictator, drug trafficker, and former CIA informant Manuel Noriega.

Citing the protection of U.S. citizens living in Panama, the lack of democracy, and illegal drug flows, the George H.W. Bush administration said Noriega must go. Within days of the invasion, he was captured, bound up and sent back to the United States to face racketeering and drug trafficking charges. U.S. forces fought on in Panama for several weeks before mopping up the operation and handing the keys back to a new president, Noriega opposition leader Guillermo Endara, who international observers said had won the 1989 election that Noriega later annulled. He was sworn in with the help of U.S. forces hours after the invasion.

As they say in school, “easy-peasy.” Could an operation to take out a modern narco kingpin and dictator in Venezuela, Nicolas Maduro, be much different?

“What I would say to you is that a Venezuela invasion does not look like Panama, it looks more like Iraq (in 2003). Venezuela is a larger, and more complicated operation than Panama,” said one retired military officer who spoke to Responsible Statecraft. He served in both the 1989 invasion and in the war in Iraq 15 years later, before spending the rest of his career in government.

“There are a lot of very specific circumstances that were in place in Panama, that we don't have in most other places,” he noted, starting with the fact that there was a U.S. embassy, garrisoned troops as part of the U.S. Southern Command (upwards of 14,000 stationed there before Operation Just Cause; 26,000 total for the invasion) and a rich intelligence network built up over the decades when Americans were running the Panama Canal zone. Most importantly, Noriega, he said, was unpopular inside and outside of the country and much more vulnerable.

“The Panamanian Defense Forces (PDF) was already fragmented and divided before the invasion. I mean, people forget that there had been a coup attempt against Noriega in October, just two months before Operation Just Cause,” points out Orlando Perez, professor of political science at the University of North Texas at Dallas and author of “Political Culture in Panama: Democracy after Invasion.”

“Also, the PDF, their deployment was centralized. It was all headquartered in Panama City, that's where most of the forces were. And so once you captured the comandancia, the headquarters, which was in Panama City, the whole thing collapsed.”

There is no U.S. embassy in Venezuela; relations have been cut off since 2019. Moreover, said the retired military officer, after a high-profile coup attempt against then-President Hugo Chavez in 2002, Maduro’s government is more coup-proof than ever, and looks more like Saddam Hussein’s Ba’ath Party in Iraq, which means it is integrated into the society in ways that ensures a lot more loyalty than Noriega, who as a military chief did not rule directly but rather through puppet presidents, from 1983 until his capture.

“This (Maduro) regime has had a long time to embed itself, and it's built sort of this political and party apparatus extending across every element of society, in every school, in every company, every office. And Noriega didn't have that. He had a much more sclerotic kind of political structure around him, mainly because he's more of a gangster,” he said.

“Look, Noriega decapitated a lot of his own leadership with purges to try and make sure that they were as loyal to him. Now they weren't going to fight for him. I mean, you know, we hit him hard, and they kind of melted away. They did fight. I mean, in all honesty, they did…but once they saw the writing on the wall they made different choices.”

The United States military has been building up hard naval and air assets and amassing troops on its nearby military installation in Puerto Rico and off the coast of Venezuela for the last month. According to reports, it could have some 16,000 personnel in the region with the arrival of the USS Gerald Ford carrier strike group.

That is hardly enough for a “Just Cause” invasion of Venezuela, note the experts who spoke with Responsible Statecraft.

“The analogy, it breaks down in many different ways. Venezuela is about 12 times larger than Panama. Panama had perhaps 2.4 million people (in 1989). That's about the population of Caracas alone. The Venezuela urban landscape is much denser and more complex than Panama City,” said Perez.

Moreover, despite very real suspected vulnerabilities on the part of Maduro, that his support is soft, that he has built it through a regime of political favors and corruption, Perez said that he thinks “there is enough of an organized resistance that (U.S.) military planners need to think about, at least consider and not dismiss.”

“So the argument is, it's brittle there, you know, they've been bought off, and they will collapse immediately. That when the Marines show up on shore, these people will collapse and there will not be a resistance. Well, you know, we don't know that. Their livelihoods, their lives, will be at stake, many of them, you know, might end up in jail or executed,” so there are plenty of incentives for them to resist, he added.

Aside from the geographic differences between the two countries (experts said it would take at least 100,000 U.S. forces or more to properly invade the country, depose Maduro, and then try to restore order), there is the matter of intelligence. The U.S. had a large military footprint in Panama since the opening of the canal in 1914 and 1999, when a treaty brokered by President Jimmy Carter to hand the canal back to the Panamanians, took effect. Through paid operatives like Noriega, the CIA had used the country as a base for Cold War-era covert ops throughout Latin America. Beyond that, the American military itself had been living, working, and laying down a semblance of roots in Panama that allowed for a level of operational awareness that just cannot be replicated in Maduro’s Venezuela.

“We had thousands of troops down there who were married to Panamanian women. They had their in-laws spread across the country. All of them hated Noriega. We had people coming in to work in the base who hated Noriega and would tell us all kinds of things,” said the retired officer. “They’d grab me because I was a Spanish-speaking officer, and they're like, let me tell you this, this, this, and this. I got guys who would tell me where the checkpoints were every day as they were coming in.”

“Here's a great story,” he added. “We got a report of Noriega militias massing in a neighborhood in Panama City, and my roommate called his girlfriend who lived there and she said it wasn't true, that's what we could do.”

The experts cautioned that the most important take-away from Panama is not that the invasion and capture of Noriega was “easy” but that, despite establishing a working democracy, it did not necessarily make life in Panama any easier. It did not stop the crime and illicit drug flows into the U.S. and, if anything, it gave Washington a false sense of how it could pursue intervention and regime change in the future. The prime example is the much larger First Gulf War of 1991, just two years later. H.W. Bush declined to depose Iraq’s Saddam Hussein at the time, but his son was convinced to follow through in 2003, resulting in one of the biggest U.S. foreign policy debacles in modern history.

“It taught us the wrong lessons, yes,” the retired U.S. military officer said. “There is this idea that this works here, therefore it’ll work there. But I think that what the policy community does is it incorporates a Cliff Notes version of history, it takes a complex situation, settles on a narrative, and then incorporates this very Cliff Notes half-assed version of what happened, and that becomes the lesson learned.”

- Venezuela regime change means invasion, chaos, and heavy losses ›

- US invasion of Panama was first step toward the 'forever wars' ›

- America First? For DC swamp, it's always 'War First' | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Elliott Abrams returns, promoting a Caracas cakewalk | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Trump’s quest to kick America's ‘Iraq War syndrome’ | Responsible Statecraft ›

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)