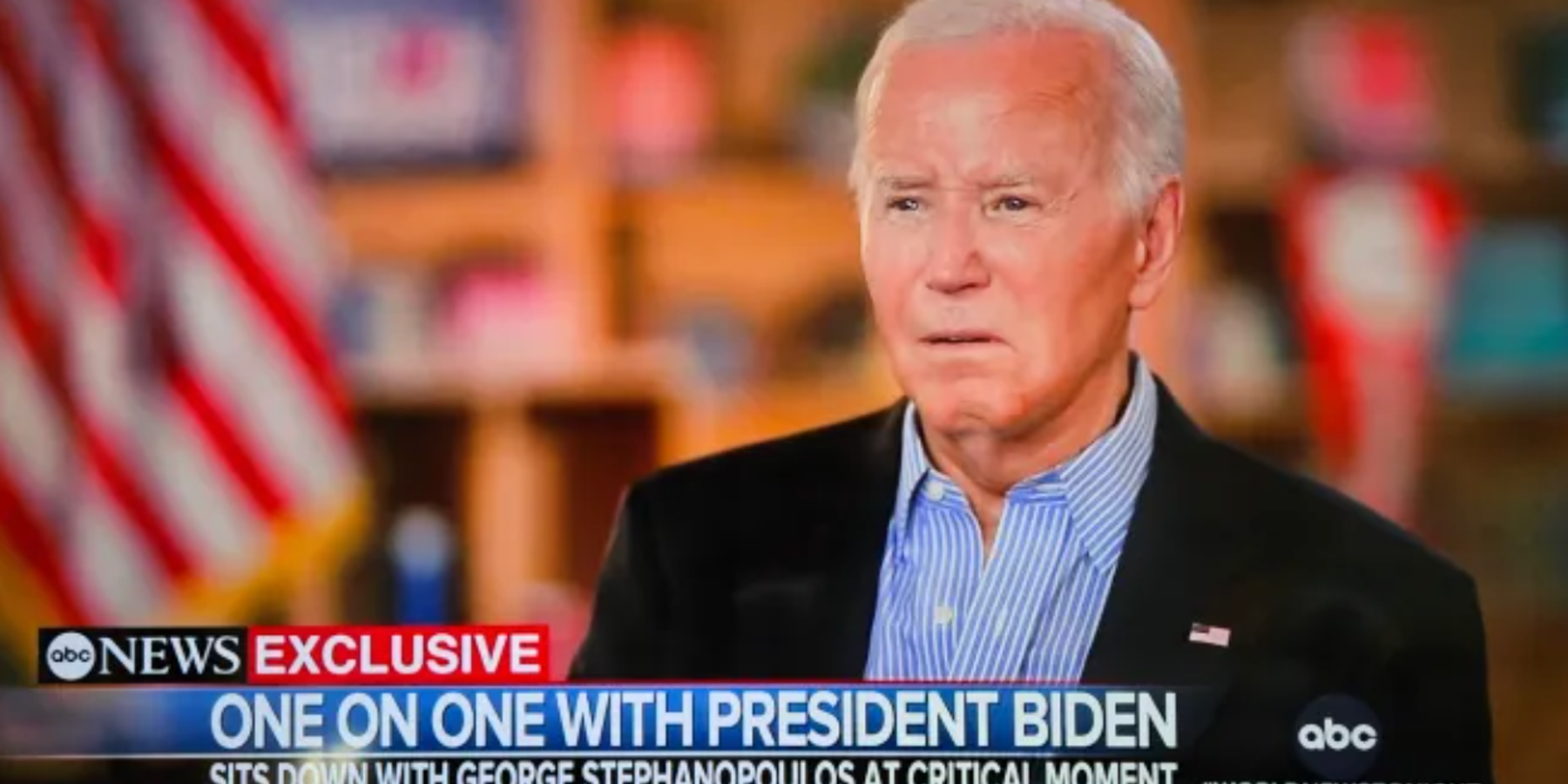

The president insisted that his campaign would continue and that he was the best candidate for the job in an interview with ABC News’ George Stephanopoulos on Friday.

Rejecting calls for him to step aside, Biden defended his determination to remain in the race by using one of his favorite foreign policy talking points, the conceit that America is the indispensable or essential nation. Building on the idea expressed by then-Secretary of State Madeleine Albright a quarter century ago, the president said, “You know, not only am I campaigning, but I'm running the world. Not — and that's not hy — sounds like hyperbole, but we are the essential nation of the world. Madeleine Albright was right.”

Later in the interview, Biden also maintained that there was no one else who could lead as well as he could. He asked Stephanopoulos, “who's gonna be able to hold NATO together like me? Who's gonna be able to be in a position where I'm able to keep the Pacific Basin in a position where we're — we're at least checkmating China now? Who's gonna — who's gonna do that? Who has that reach?”

The president would have everyone believe that he is an irreplaceable leader of the indispensable nation, but the idea that he has been “running the world” betrays a dangerous arrogance about both the president’s importance and America’s international role. The U.S. didn’t “run” the world even at the height of its power, and it is foolish to think that it could in an increasingly multipolar world.

Biden’s belief helps explain why the president refuses to end his campaign, but it also points to a key flaw in the current strategy of the United States. Washington is overstretched around the world and has more commitments than it can realistically honor. That overstretch is a result of the false belief that the world can’t do without American “leadership.” U.S. leaders refuse to shift burdens to anyone else in any part of the world because they wrongly assume that no other countries can bear them.

Just as Biden clings to his position when there are others able to take his place, the U.S. clings to its current strategy because it doesn’t want to accept a world where it isn’t “essential.”

It is beyond the competence of any state to be the “essential nation.” It is a self-important fantasy to believe that the world depends on any one country to such a great extent. When Washington has acted on this belief in its supposedly essential role, it has done considerable harm to its own interests and to other countries. There have been many crises and conflicts where American involvement was not needed and where that involvement made matters worse than they were before.

Everyone can see that in obvious cases like the Iraq war or the intervention in Libya, but it also applies to the frequent use of broad sanctions from Venezuela to Iran to North Korea. We can see it in the U.S. supporting role in the Saudi coalition war on Yemen, and we see it again today in Biden's support for the war in Gaza. In those instances when U.S. involvement has not been destructive, it is often not required.

Insisting that we are essential to the rest of the globe is how our leaders excuse constant meddling in things that have little or nothing to do with America's interests. It is a handy way to shut down the policy debate by claiming that the U.S. really has no choice except to intervene and take sides in disputes and conflicts where we have nothing vital at stake. That is how the list of commitments keeps growing and never gets any smaller.

No matter what one thinks about Biden’s fitness, the limits of American power and the relative decline of that power in recent decades make the indispensable nation belief more absurd than ever. Albright’s original claim wasn’t true when she made it, and it certainly isn’t today. It is a measure of how dated Biden’s worldview is that he still cites a Clinton-era phrase as if it were relevant to current realities.

Our current foreign policy is unsustainable given America’s limitations, and we need to have a much less ambitious one in the years to come if we are to avoid the costs of more unnecessary conflicts.

No president, regardless of age or condition, should imagine that he “runs the world” and none should try. No one can possibly shoulder that much responsibility, and no one is up to the task. Biden isn’t up to “running the world,” but then neither is anyone else.