A possible diplomatic shift in the war in Ukraine may have gone largely unnoticed when Kiev appeared to signal that it might be willing to give up its aspiration to become a member of NATO. Or at least downgrading its urgency.

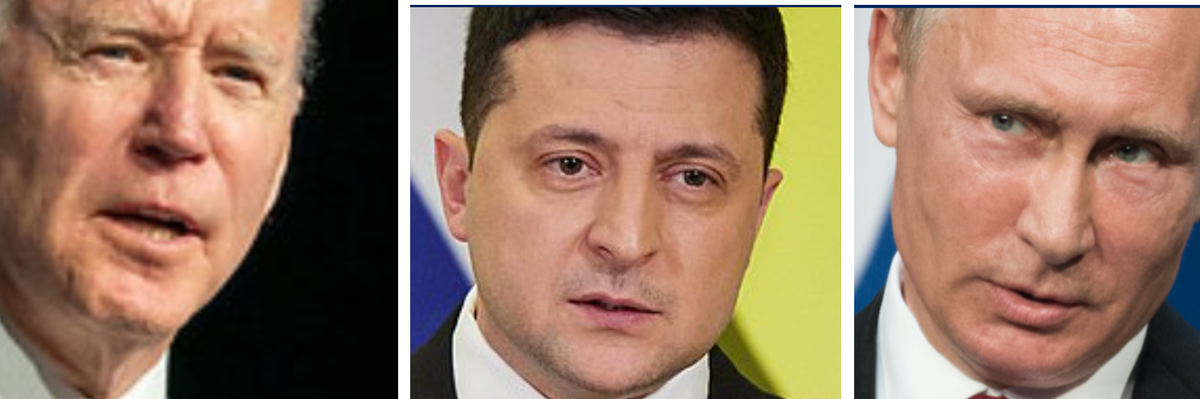

It was reported in early November that the administration was privately lobbying President Zelensky to repeal his decree banning negotiations with the present leadership in Russia. Following National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan’s visit to Kyiv on November 8, Zelensky announced a new openness to diplomacy with Putin and urged the international community to “force Russia into real peace talks.”

Zelensky’s new willingness to talk, however, was predicated upon several preconditions that are likely non-starters for Moscow, including “the return of all of Ukraine’s occupied lands, compensation for damage caused by the war and the prosecution of war crimes,” according to the Associated Press. He reiterated this on Tuesday in remarks before the G20 in Bali, in which he issued a "10 point plan for peace."

Though Zelensky’s preconditions make talks with Putin unlikely, Washington apparently believes that Zelensky may be open to flexibility. “They believe that Zelensky would probably endorse negotiations and eventually accept concessions, as he suggested he would early in the war,” according to U.S. officials who spoke with the Washington Post.

Is NATO one of those concessions? There was no mention of it in his 10-point plan.

At the heart of the war is the issue of the alliance’s eastward expansion into Ukraine. At the same time Zelensky issued his decree banning negotiations with Putin, following Russia’s announcement in September that it would annex Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia, he also renewed the plea for accelerated NATO membership.

Zelensky said at the time that “we must de jure record everything we have already achieved de facto.” He continued:

We are de facto allies. This has already been achieved. De facto, we have already completed our path to NATO. De facto, we have already proven interoperability with the Alliance’s standards, they are real for Ukraine — real on the battlefield and in all aspects of our interaction.

We trust each other, we help each other and we protect each other. This is what the Alliance is. De facto.

Today, Ukraine is applying to make it de jure.

That appeal, as we reported here, fell flat among Western partners. On November 10, the "de jure" language may have changed, albeit subtly. In an interview with Reuters, Ukrainian defense minister Oleksii Reznikov repeated the first part of Zelensky’s formulation that “we have become a NATO partner de facto right now.” But seemed to amend the second part. He said, "It doesn't matter when we become a member of the NATO alliance de jure.”

The question is, did he mean to suggest that Kyiv is accepting a new model of relationship with NATO — de facto membership — dropping the urgency for de jure membership in NATO?

The suggestion of such a turn is further illustrated by the analogy Reznikov made during the interview. He said that “Kyiv’s broader defense push” included working towards making Ukraine more independent in its future ability to defend itself. Then he said, “I think the best answer [can be seen] in Israel ... developing their national industry for their armed forces. It made them independent."

“We are trying,” he explained, “to be like Israel — more independent during the next years.”

The unstated significance of the model is that Israel is not a member of NATO, nor even a treaty ally. But it is a strong partner with a special relationship and gets $3 billion a year in defense assistance from Washington.

If Reznikov’s carefully worded amendment to Zelensky’s formulation was scripted and not spontaneous, is it possible that Ukraine just dropped the request for NATO membership — something he was willing to do early on in the war? This, as they say, remains to be seen.