Americans appear increasingly pessimistic about the United States’ future geopolitical position.

In fact, according to one poll this September, 50 percent of Americans believe it is “likely” or “very likely” that the United States will no longer be a superpower 10 years from now. Only 32 percent of the nationally representative sample polled disagree. This pessimism is, moreover, remarkably bipartisan: 55 percent of Democrats and 56 percent of Republicans agree that the U.S. will lose its superpower status a decade from now.

Whether the United States is objectively declining is open to debate among international relations scholars, though there is a degree of consensus that the United States has declined in relative terms compared to its peak during the “unipolar moment” after the fall of the Soviet Union. This sense of pessimism among both the American public and its elites presents a danger: that politicians will attempt to use this declinist narrative for their own, narrow political ends, calling for the United States to reflexively wield its power abroad and overspend on defense.

Indeed, my own academic research has found that this is the typical response of politicians — in the United States and elsewhere — when faced with the prospect of international decline. Worryingly, politicians often call for these policies whether or not that decline is actually occurring.

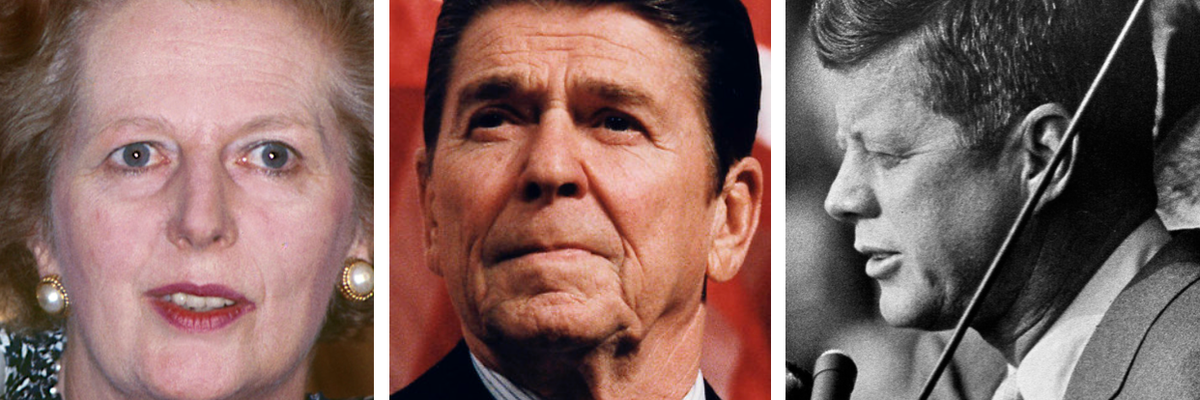

John F. Kennedy, for example, used the specter of a non-existent “missile gap” between the United States and Soviet Union as an example of the degree to which the United States had fallen behind the USSR during the previous eight years of the Eisenhower administration. Kennedy mobilized a group of journalists, academics, bipartisan politicians, and citizens during his 1960 presidential campaign to hammer home this narrative of relative decline.

The mobilization worked to significant political effect (he won), despite the fact that the missile gap did not exist. Knowing this but refusing to intervene publicly out of a fear of revealing sensitive intelligence, Eisenhower privately referred to the “missile gap” issue as a “useful piece of demagoguery.” Worryingly, Kennedy’s declinist narrative was so compelling politically that he found the talk of American decline exceptionally hard to walk back once in office. Even after receiving intelligence briefings that the “missile gap” was a myth, Kennedy stayed the course, insisting that the defense build-up he promised as a candidate would continue apace.

As stated, this type of response to international decline is not uniquely American. Numerous world leaders have used a narrative of their country’s backsliding as a potent political rallying cry. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher responded to British decline in the 1970s to partly justify her military response to the Argentine invasion of the Falklands. Ronald Reagan promised, well before former President Donald Trump did, to “make America great again” via increased defense spending.

More recently, Japanese politician Tōru Hashimoto formed a political party designed to return Japan to greatness. In each of these cases, political leaders used narratives of decline — whether they were objectively occurring or not — to justify “punching back” against that perceived decline. While it is possible that leaders advocate for retrenchment in the face of a weakening international position (the twin policies of perestroika and glasnost instituted by Mikhail Gorbachev are one set of examples), the penchant is often to do more rather than less.

Narratives of decline are particularly powerful, for, as Josef Joffe describes, “the message [declinism] has worked wonders since time immemorial because doom, in biblical as well as political prophecy, always comes with a shiny flip side, which is redemption."

Indeed, commonplace among these narratives are paths to renewal. Both Kennedy and Reagan promised a revival of American spirit and power. Kennedy referred to a “new frontier” that would define America in the 1960s. Reagan promised “morning in America.”

Looking to the future, my research suggests that Republicans will attempt to use the specter of American decline as a political critique of the Biden administration in the 2022 midterms and 2024 presidential election. Republicans may criticize Biden’s decision to withdraw from Afghanistan, as well as his failure to prevent Russia from invading Ukraine.

Republicans are also highly likely to attack Biden for not being confrontational enough against China. These attacks are often most effective when they come from political outsiders, who are able to differentiate themselves from the track record of the establishment that they are criticizing.

Rather than attempting to conjure back a historical anomaly — American unipolarity — both Democrats and Republicans should instead recognize that primacy is contributing to, rather than halting, American decline. In the face of a shifting global power balance, recognition of relative American decline should lead to calls for doing less abroad militarily and investing more at home.

Sometimes, doing less is, in fact, doing more. As Samuel Huntington observed nearly 30 years ago, declinism may serve as a galvanizing function for the United States.