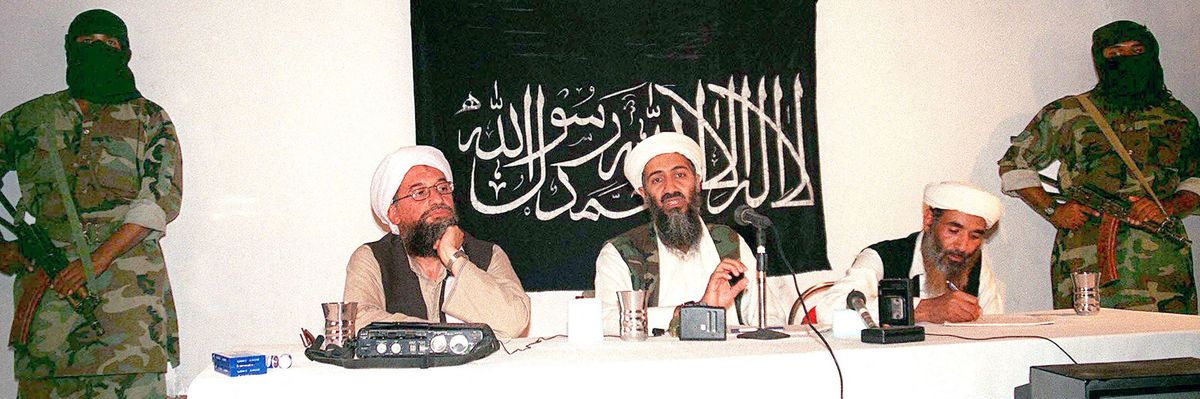

The killing of al-Qaida leader Ayman al-Zawahiri with a drone strike on a residence in Kabul was inevitable once it became possible. The lethal raid that eliminated previous leader Osama bin Laden 11 years ago was widely accepted, and the killings of purported “number three” men in al-Qaida were so numerous that the third-ranking position in the group came to be regarded as the most hazardous job in the world. Zawahiri was the number two before he succeeded bin Laden, and of course he had to go too.

The usual historical reference made in connection with this execution is to the 9/11 attacks 21 years ago. Zawahiri had enough connection to that event, at least on an ex officio basis, to deserve his punishment. But it is a mistake to describe him as a mastermind of 9/11. That role was played by Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, currently incarcerated at Guantanamo and awaiting a trial by military tribunal that keeps getting delayed.

Since joining forces with bin Ladin, Zawahiri functioned primarily as an ideologist. As an operational terrorist leader, his place in history is more as a failure than as a success. His Egyptian Islamic Jihad, before Zawahiri merged it with al-Qaida, conducted a terrorist campaign in the 1990s that failed to achieve its goal — which more peaceful activity by crowds in Cairo achieved years later — of overthrowing Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak.

There always is general reason to doubt how much difference decapitation — assassination of an individual leader — makes to the capability of a terrorist group. There is especially reason for doubt in the case of Zawahiri and al-Qaida. The documents captured in the raid that killed bin Ladin showed that during his last years in hiding bin Ladin was not functioning as an operational leader. His life then was more of a struggle to communicate with and exhort his followers. There is little reason to believe, based on what we know so far, that the life of Zawahiri in hiding was appreciably different. National Security Council spokesman John Kirby was probably overselling the significance of Zawahiri’s removal for the strength of al-Qaida when he talked this morning about the drone strike, but at least he was speaking accurately in characterizing Zawahiri’s role as one of “exhorting” followers.

Moreover, insofar as threats from such Sunni extremist networks persist, it probably is less from what remains of al-Qaida central than from affiliates outside South Asia that have used the al-Qaida brand name but do not need any direction from al-Qaida central to act. The affiliate that is based in Yemen came closer to accomplishing post-9/11 attacks against the United States than did the parent organization. Then there is the former al-Qaida affiliate that grew into an al-Qaida rival and became known as Islamic State or ISIS.

The killing in Kabul underscores a couple of aspects of U.S. policy toward Afghanistan, from which the United States withdrew its last military forces nearly one year ago. At that time, one of the most frequently voiced arguments against the withdrawal was that U.S. military boots on the ground were necessary for effective collection of counterterrorist intelligence. The intelligence coup in locating Zawahiri with sufficient accuracy and certainty to make the drone strike possible is a pointed refutation of that argument.

There continues to be an issue of what U.S. policy should be toward the Taliban, the current governing authority in Afghanistan. Attention to the issue is likely to rise, as the United States accuses the Taliban of violating the withdrawal agreement — which the Trump administration had negotiated — by hosting Zawahiri, and the Taliban accuse the United States of violating it by conducting the drone strike.

Another comment often heard from those opposing the withdrawal was that a relationship was sure to persist between the Taliban and al-Qaida. But those making that comment were focusing on the wrong question. Of course there was going to be some sort of connection to individuals with whom the Taliban had past relations — and it appears that the Haqqani group, which can be considered a wing of the Taliban, was providing hospitality to Zawahiri — but the important question is what type of relationship there will be now, and whether the Taliban will use their influence in such relationships to restrain or to condone any terrorist activity by the likes of al-Qaida.

The Taliban, who gained power in Afghanistan last year without assistance from al-Qaida that was comparable to what it had needed and used in an earlier phase of the Afghan civil war, has good reason not to condone international terrorist operations, by al-Qaida or by anyone else, mounted from Afghan soil. Such activity can only complicate the Taliban’s efforts to achieve international recognition and cooperation, and to establish order and control inside all of Afghanistan. The one circumstance that would be likely to change that calculation would be any active stoking by the United States of a rekindled war in the country.