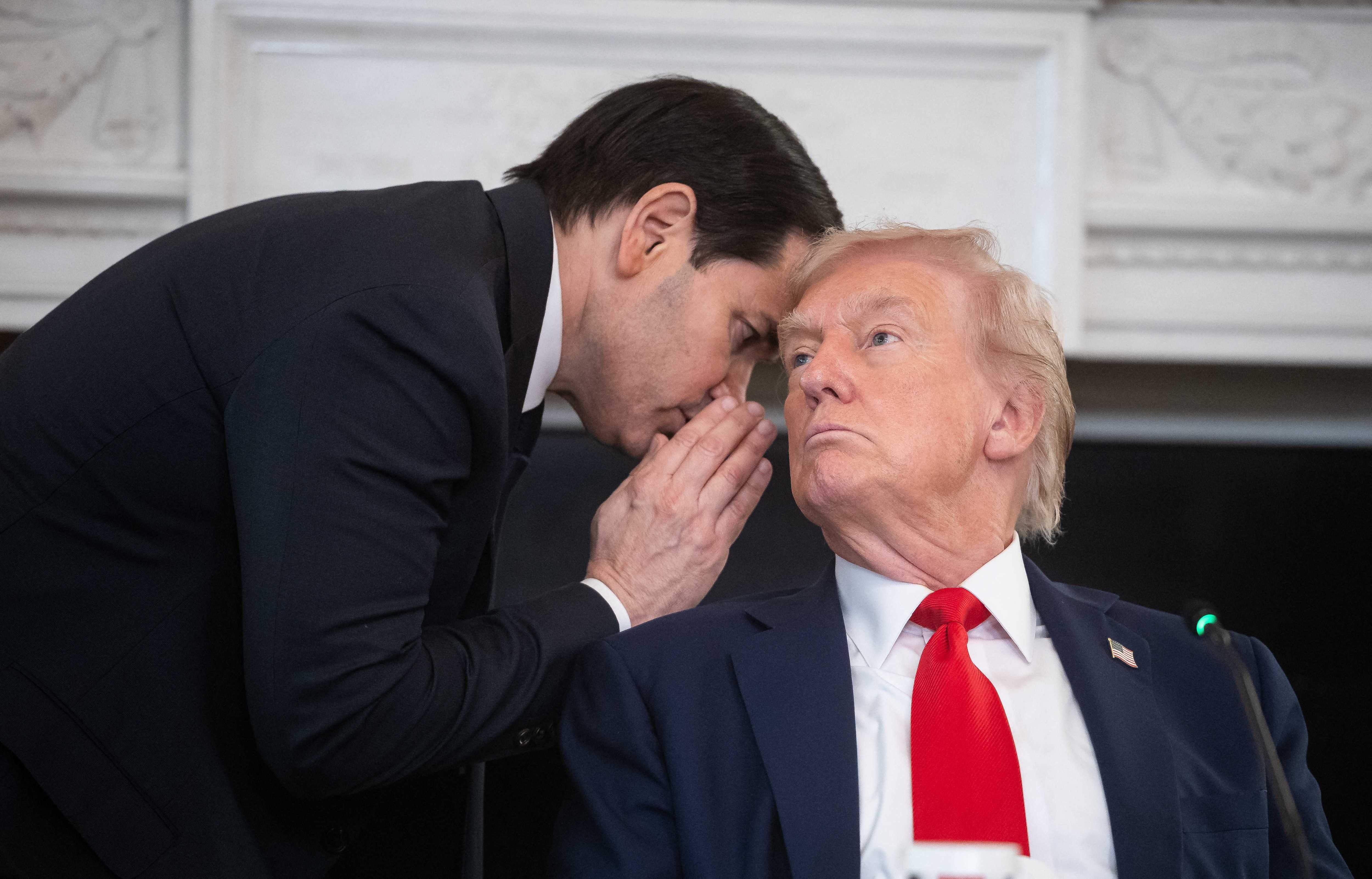

It appears that Secretary of State Marco Rubio is emerging victorious in the internal Trump administration battle over the direction of U.S. policy toward Venezuela.

The New York Times reported on Oct. 6 that White House special envoy Richard Grenell — who, after meeting President Nicolas Maduro in Caracas this January inked deportation agreements, won the release of American prisoners, and secured energy licenses for U.S. and European oil majors — was told by President Donald Trump to stop all diplomatic outreach toward the resource-rich South American nation.

The news comes as some Trump officials, particularly Rubio, have pushed the president to escalate tensions, which he has done by dispatching a major naval deployment to the Southern Caribbean in an alleged counternarcotics operation, killing over 20 alleged drug traffickers in at least four strikes against go-fast boats since early September.

Rubio, a Cuban-American former senator from Florida, has long been a leading voice in Washington for a combination of “maximum pressure” sanctions and related regime change efforts against Maduro and his predecessor, Hugo Chavez.

In January 2019, Rubio asked Trump to recognize little-known National Assembly leader Juan Guaidó as interim president, which he did the next day, prompting Maduro to break off diplomatic ties with Washington. Amid a series of failed military uprisings spurred on by Guaidó that year, Rubio tweeted the Miami jail photo of deposed Panamanian leader Manuel Noriega and images of a bloody Muammar Gaddafi, the Libyan ruler, minutes before his death, in an apparent threat to Maduro. Before that, under President Barack Obama, Rubio spearheaded some of the first calls to sanction top Venezuelan officials over alleged rights abuses.

Despite catching then-candidate Trump’s ire on the 2016 campaign trail, Rubio, who also serves as the president’s national security adviser, has since become Trump’s most trusted voice on foreign policy, “amassing the kind of foreign policy power last seen by Henry Kissinger,” according to a recent Miami Herald profile.

His ideological flexibility on issues such as negotiations with Russia and cuts to democracy programs abroad has seemingly not extended to his almost obsessive agenda to oust the Maduro government. Yet while Rubio once invoked democracy and the rule of law to push for Maduro’s removal, he and leading figures in Venezuela’s opposition have since weaponized the 2020 indictment against Maduro in a New York federal court to convert Venezuela — which Trump administration officials allege is flooding the U.S. with drugs and criminals — into a purely law enforcement matter.

Rubio has found willing allies on both sides of the aisle in his maximum pressure approach. On Capitol Hill, GOP Florida lawmakers Sen. Rick Scott, Rep. Mario Diaz-Balart, Rep. María Elvira Salazar and Rep. Carlos Giménez, along with Democratic Reps. Debbie Wasserman-Schultz and Jared Moskowitz, have all backed Rubio’s hardline policy. Many of these legislators maintain close ties to prominent Venezuelan-American anti-Maduro donors and activists like Ernesto Ackerman, who has called Rubio “our general,” and Kennedy Bolívar, who regularly shares content with him alongside Rubio and Scott.

During Trump’s first administration, when Rubio served as “shadow secretary of state for Latin America,” then-national security adviser John Bolton, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, and Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin also lined up behind regime change in the country. Trump’s special representative for Venezuela Elliott Abrams and his deputy, Carrie Filipetti — now chairman and executive director, respectively, of the neoconservative Vandenberg Coalition — with whom Rubio would regularly consult, played important operational roles in those efforts.

At the White House, longtime Rubio ally and former pro-Cuba embargo lobbyist Mauricio Claver-Carone, who also served initially as the State Department’s Special Envoy for Latin America in Trump’s current term, was an architect of sanctions targeting Venezuela’s oil industry, which economists say fueled an unprecedented exodus of Venezuelans from the country. “Once Mauricio came in, the policy went on overdrive,” Rubio told the New York Times in 2019.

This year’s Nobel Peace Prize winner, Venezuelan opposition leader Maria Corina Machado, whose disqualification from running in the July 2024 presidential elections resulted in the candidacy of diplomat Edmundo González, has arguably been the leading proponent of Rubio’s approach. Despite vote tallies from 83% of the country’s electoral precincts showing Gonzalez with an insurmountable lead of 67% of the ballots cast, the National Electoral Council declared that Maduro had won with 51% of the vote, a result denounced by international observer missions as lacking in transparency.

Amid a crackdown against the opposition, Gonzalez fled to Spain soon after the election, while Machado went into hiding. But she has been participating virtually in efforts by her supporters in exile to lobby for regime change, including in conferences with executives and financiers in New York and Houston at which she has depicted Venezuela as a trillion-dollar investment opportunity.

For over two decades, U.S. officials have lined up behind opposition figures working to install a government in Caracas friendlier to U.S. corporate interests. When the Chavez administration nationalized all privately owned oil fields in 2007, U.S. and European firms Chevron and Repsol played by the new rules of engagement, reconfiguring their joint ventures with state-run PDVSA. But ExxonMobil — whose CEO at the time, Rex Tillerson, would become Trump’s first secretary of state — rejected them, leading to years of litigation against Venezuela’s government.

Former Exxon counsel involved in the litigation, Carlos Vecchio, would in 2019 become interim president Guaido’s ambassador in Washington, working closely with fellow Popular Will party co-founder Leopoldo Lopez, special envoy on migration David Smolansky, OAS ambassador Gustavo Tarre, Lima Group ambassador Julio Borges and opposition negotiator Freddy Guevara, among others, to hasten Maduro’s departure.

These voices have featured prominently in the media and at U.S. think tanks like CSIS, AS/COA and the Manhattan Institute, while lobbyists at the Cormac Group and Continental Strategy have represented the anti-Maduro opposition and the neighboring government of Guyana — where Exxon discovered massive offshore deposits in territorially disputed waters after departing Venezuela — in their efforts to isolate Maduro regionally and levy harsher sanctions against the country’s economy.

U.S. government funding through USAID and the National Endowment for Democracy and the seizure of Venezuelan assets abroad have also underwritten some of these efforts. Much of the assistance earmarked toward Venezuela has gone toward aid relief and civil society groups, but some has been used to influence the policy debate in Washington and bankroll opposition parties while yet another portion was allegedly siphoned off by Guaidó and his inner circle.

When other approaches appear to have failed, military adventurism has been pursued. In 2020, former Green Beret Jordan Boudreau, after claiming to sign a contract with Guaidó and his Miami-based associates JJ Rendon and Sergio Vergara, led a failed invasion intended to oust Maduro. The Trump administration and Guaidó denied any involvement. More recently Blackwater founder Erik Prince has claimed to have raised over $1 million for an operation designed to achieve Maduro’s downfall.

Meanwhile, the Justice Department recently raised the bounty for the arrest and/or conviction of Maduro to $50 million and designated the “Cartel de los Soles,” which he allegedly heads, as a foreign terrorist organization.

U.S. intelligence agencies have denied claims, including by Rubio himself, that another Venezuelan transnational criminal organization, Tren de Aragua, is led by Maduro.

Yet this hasn’t stopped the administration from using the allegation — which analysts say is being used to justify the military buildup near Venezuela — as a pretext to also strip Temporary Protected Status for 600,000 Venezuelans, many living in the South Florida congressional districts which overwhelmingly voted for Trump.

Many of the overwhelmingly anti-Maduro voters in these districts, a majority of whom also reject U.S. military action to depose him, are now rethinking their decision, mostly over his deportations and termination of protected status for migrants, according to reports this spring.

For now, Rubio seems to be firmly in the driver’s seat of the administration’s muscular approach to Venezuela — even if his traditional base of supporters, and most Americans for that matter, aren’t going along for the ride.

- Grenell vs. Rubio: Team Trump's competing Latin America visions ›

- What awaits Marco Rubio in the Caribbean ›

- Toppling Maduro means invading Venezuela. Are we ready? | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Rand Paul to Trump: Don't 'abandon' MAGA over Maduro regime change | Responsible Statecraft ›

- America First? For DC swamp, it's always 'War First' | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Dick Cheney's ghost has a playbook for war in Venezuela | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Left-right backlash against war with Venezuela is growing | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Experts at oil & weapons-funded think tank: 'Go big' in Venezuela | Responsible Statecraft ›

- After ousting Maduro, Trump and Rubio put Cuba on notice | Responsible Statecraft ›