On April 2 — christened “Liberation Day” — President Donald Trump declared a national emergency in response to the “large and persistent U.S. trade deficit” and “unfair” economic practices by foreign countries that, according to Trump, hurt the American people by undermining the U.S. industry and employment.

In response, the president announced a minimum 10% tariff on all U.S. imports, plus higher tariffs, ranging from 11% to 50%, on imports from nearly 60 countries. These “reciprocal tariffs,” based on trade deficit calculations, targeted over 180 countries and territories. After a week of turmoil in the stock and bond markets, Trump announced a 90-day pause on reciprocal tariffs over 10 percent for most countries except China.

However, the reality of imposing tariffs and changing global trade dynamics is more complex. For example, Vietnam, like other Southeast Asian countries, has long maintained a non-aligned stance on the global geopolitical front and navigating through the choppy waters of great power competition. Hence, Vietnam's response to Trump’s moves should be seen as a reflection of its foreign policy priorities rooted in its national interests, including economic development, and its commitment to non-alignment.

Vietnam has long been a central figure in the escalation of U.S.-China trade tensions since they began in earnest back in 2018, when President Trump placed 10% tariffs on Chinese imports. In the years since, the U.S. trade deficit with Vietnam has tripled, reaching $123.5 billion in 2024, the last year with complete data. One of the key catalysts for this change is the strategic “decoupling” approach by companies that have relocated production and manufacturing from China to other countries, including Vietnam, in an effort to diversify their supply chains and appease Washington’s concerns about Beijing’s economic ascendancy. With rising geopolitical uncertainties, cheap alternative manufacturing hubs, of which Vietnam has become a prime example, have become attractive substitutes for China.

Vietnam is also a backdoor for Chinese exports, importing and assembling Chinese goods with minimal added value before reexporting them to the United States. Peter Navarro, Trump’s senior counselor for trade and manufacturing, alleged in a recent interview that Vietnam is guilty of “nontariff cheating,” by which he meant Hanoi permits China to ship its products through Vietnam to disguise their origin and thus avoid U.S. tariffs. These reasons, coupled with Vietnam’s large trade surplus, have resulted in the administration’s perception that the country poses a major threat to the U.S. economy and the welfare of American workers.

Vietnam has tried to be responsive to the Trump administration’s demands, which have centered around reducing the trade deficit, addressing transshipment issues, and enhancing intellectual property rights. Vietnam’s Ministry of Finance is currently working on enhancing customs information-sharing with the U.S. and drafting a comprehensive bilateral trade agreement that includes provisions on taxation and intellectual property rights — all in response to concerns raised by the Trump administration. In fact, Vietnam was the first and remains the only Southeast Asian country whose leader has spoken directly to Trump about the tariffs.

After receiving a whopping 46% tariff rate on Liberation Day, Vietnam’s Communist Party General Secretary To Lam reached out to Trump in a call that the U.S. president would later describe as “very productive,” Vietnam offered to reduce tariffs on U.S. goods to zero, according to Trump, who said Hanoi is also addressing non-tariff issues raised by U.S. officials. Vietnam’s various ministries are tasked with examining existing legal frameworks and proposing changes.

Vietnam also authorized the operation of Starlink, the satellite internet service owned by Elon Musk, and agreed to expedite approvals for a proposed $1.5 billion Trump resort. Most important, Vietnam sent a top official, Deputy Prime Minister Ho Duc Phoc, to the U.S. for negotiations centered on improving the trade imbalance and tackling transhipment issues, where goods (specifically Chinese goods) are shipped through Vietnam to avoid tariffs or other trade restrictions imposed on countries such as China. To increase U.S. exports to Vietnam, Hanoi has struck a deal under which Hanoi agreed to buy a fleet of F-16 fighter jets.

So why is Vietnam yielding and moving to comply with the Trump administration’s demands?

One of Vietnam’s core interests includes defending its territorial claims in the South China Sea against Chinese pressure and aggression. Over the past few years, China has harassed Vietnamese fishermen near the Paracel Islands, most recently in an assault and seizure incident last October. By maintaining close diplomatic, economic, and military relations with Washington, Vietnam feels more protected from Chinese aggression. There is, however, a fine line between enhancing military cooperation with the Americans in pursuit of deterrence and provoking escalation in a potentially explosive conflict. The F-16 fighter deal could “stir up troubles” in the region, signaling to China increased U.S. military influence in the region that could call Hanoi’s non-alignment into question.

The Trump administration should realize that Vietnam is centering its foreign and trade policy on its own national interests and will happily engage with whichever foreign power is willing to help it enhance its economic development and bolster its national security. As a result, at the same time that Vietnam is responding in a friendly manner to Trump’s trade demands, it continues to cultivate close trade relations with Beijing, whose large manufacturing base, high technological capacity, and vast market make it its most important trade partner.

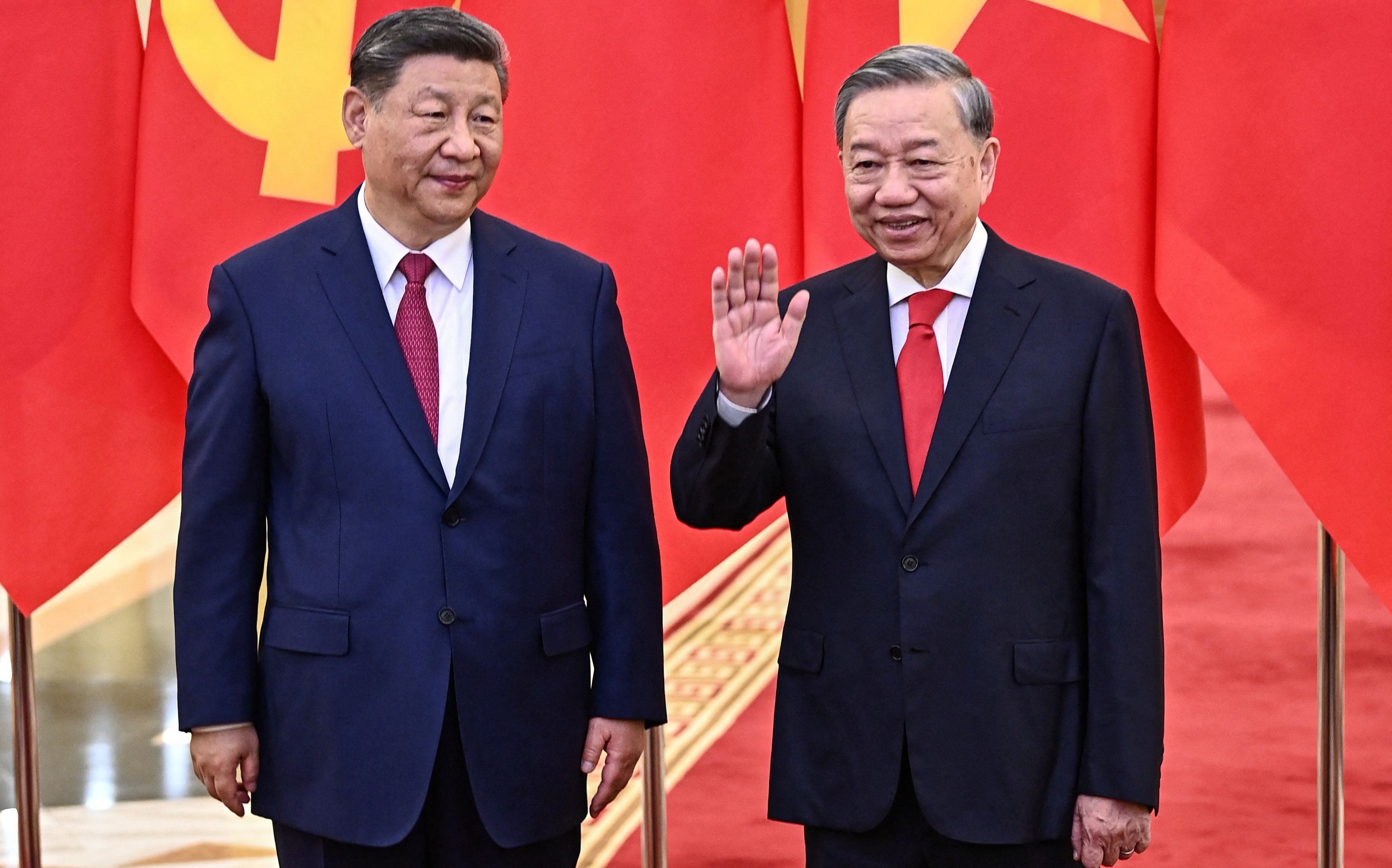

For example, during Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Vietnam on April 14, the two countries signed 45 deals ranging from increasing digital connectivity and infrastructure to cooperating in emerging fields such as artificial intelligence and green energy, to further deepen bilateral economic ties. For his part, Xi vowed to expand Vietnam’s access to the Chinese market.

Vietnam’s recent actions with regard to the trade war are ultimately a reflection of its own national interests. Its decision to strike a deal with the U.S. for the purchase of fighter aircraft signals that, even while looking to cater to Trump’s trade demands, it will do so only in ways that enhance its economic and national security interests, as defined by the national government.

The U.S. should work with like-minded countries to strengthen bilateral and multilateral ties while decreasing its dependence on Chinese manufacturing exports. Through strategic partnerships, the U.S. can help address important issues like the transshipment of Chinese goods. Targeting Vietnam alone on that issue, however, will likely result only in Chinese companies diverting goods to Vietnam’s neighbors, such as Cambodia, Thailand, or Myanmar.

Rather than growing frustrated at Vietnam’s burgeoning trade relationship with China and seeing it as a direct threat to U.S. interests within the prism of great power competition, Washington should take the opportunity presented by Hanoi’s vow to open its markets much wider to U.S. exports. Indeed, there have been recent talks of collaboration between the two in areas such as energy, technology, and education.

By embracing policies based on pragmatism and mutual interest, the U.S. can remain a strategic partner to Vietnam while addressing its concerns amid the historic shifts in global trade dynamics.