In the early hours of Sunday morning, Russia launched its largest air attack on Ukraine to date, including over 800 drones and 13 ballistic missiles. Cities across the country came under fire, and a government building in Kyiv was damaged.

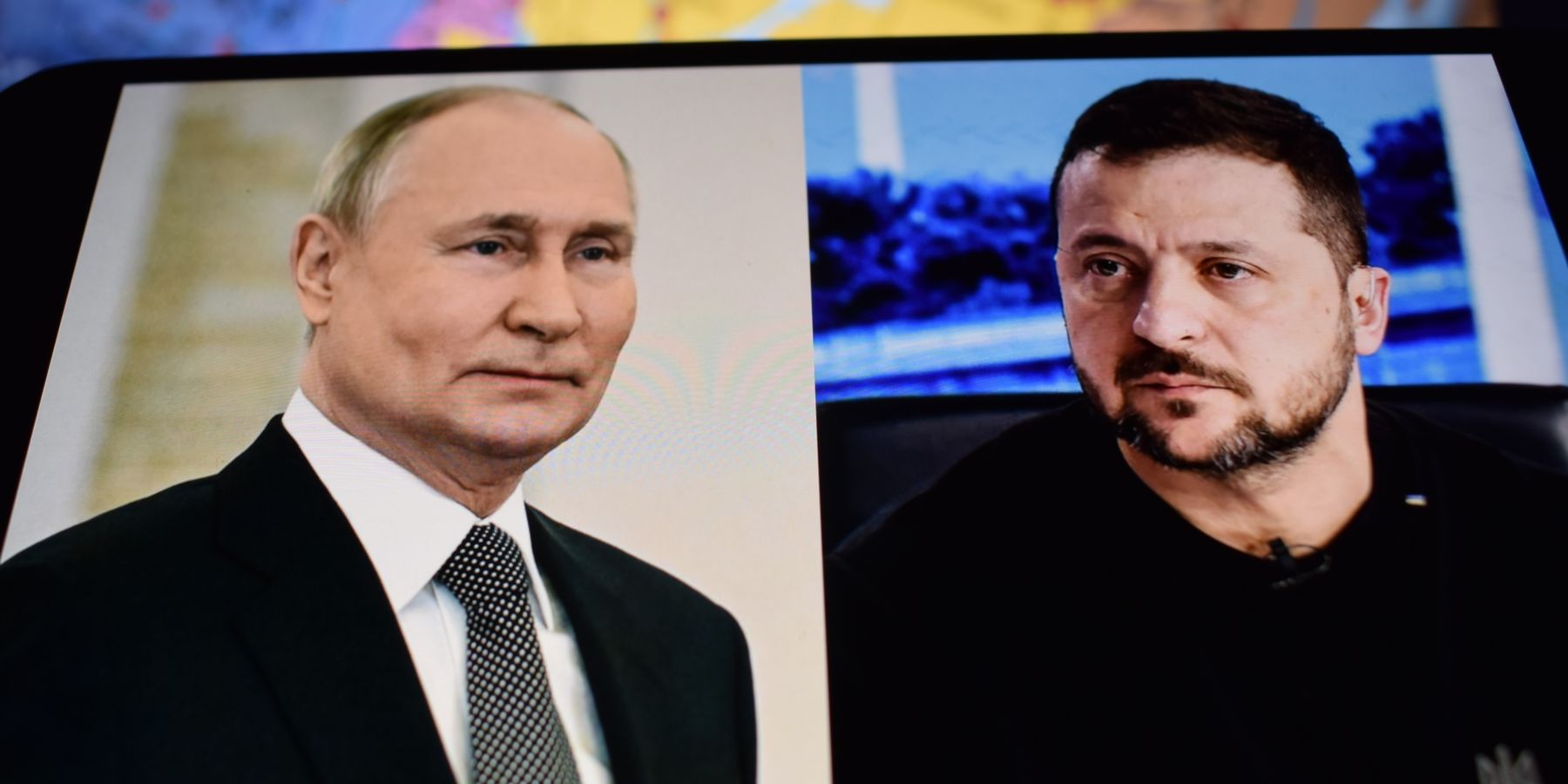

Officials in Europe and the United States were quick to condemn the attacks as evidence that Vladimir Putin is not serious about ending Russia’s nearly four-year conflict with Ukraine. They are right. Putin is not yet ready to stop fighting. And why would he be? After all, his army has the upper hand on the battlefield while Ukraine struggles with manpower shortages and materiel deficiencies.

Putin may, however, be ready to start bargaining over what the end to the war might look like, and signaled as much at last week’s Shanghai Cooperation Organization meeting in China. “It seems to me that if common sense prevails, it will be possible to agree on an acceptable solution to end this conflict,” he told reporters in Beijing.

Let’s hope that U.S. President Donald Trump is paying attention. Though his face-to-face with Putin in Alaska failed to achieve the desired results, Trump can still jumpstart flagging efforts to end the war in Ukraine. But to do so, he will need to ignore voices calling for more sanctions or military pressure to be put on Russia.

Instead, he should double down on diplomacy by initiating serious working level discussions between Washington, Moscow, and Kyiv that can begin to hash out the terms of a settlement. This move may be unpopular, but real negotiations have to start sometime, and waiting won’t make peace easier to reach.

Each year since it began, Putin has spoken about the war in Ukraine at the annual summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a multilateral group that includes China, Russia, and India among other states. His remarks have typically emphasized three main themes. First, he has countered the narrative that Russia is the aggressor in Ukraine, blaming the United States and Europe for meddling in Ukraine’s elections and pushing NATO’s boundaries closer to Russia’s borders.

Second, he has criticized the sanctions imposed on Russia by the West. Finally, he has thanked fellow SCO members for their support and efforts to work toward peace.

This year seemed different. Though his prepared remarks reiterated well-worn criticisms of NATO expansion and appreciation for Russia’s partners, in sideline conversations and answers to press questions he went further, expressing optimism about the war’s trajectory, observing that there might be a “light at the end of the tunnel,” and discussing Russia’s conditions for peace — those that are non-negotiable and those where some compromise might be reached.

There are clear limits to what Putin will agree to. Yet the positions Putin has outlined recently — in China, Alaska, and in-between — are not quite as maximalist as they were a year ago. There appears to be some bargaining space on key issues that could pave a pathway to peace if the Trump administration plays its cards right.

For example, while in China, Putin made clear once again that Ukraine’s membership in NATO is a redline for Russia, but also confirmed that Moscow does not object to Ukraine’s entrance into the EU (of course, only other EU member states can offer Kyiv membership in the economic and political union).

Putin also seemed open to discussing some kind of security guarantee for Ukraine, though it was unclear what this would entail. Putin may still be focused on the model proposed in Istanbul in which a group of countries including Russia, would guarantee Ukraine’s security. This is a non-starter for Kyiv, just as Putin is likely to veto Europe’s “reassurance force” plan.

But it’s possible that in the context of serious negotiations Putin might be open to other security arrangements for Ukraine, for example some types of Western military assistance during peacetime, Ukraine’s long-term defense industrial cooperation with Europe, or promises of additional U.S. military aid and intelligence sharing in case Russia attacks Ukraine again. Elsewhere, Moscow has signaled some flexibility on Russia’s “demilitarization” demand suggesting it would not object to a defensively armed Ukrainian military force.

Putin appears somewhat less willing to give ground on territory. Still, he noted in China that Russia would be willing to work with the United States (or even Ukraine) to oversee the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant. He continues to seek full control of Donetsk but appears satisfied freezing the lines of contact in Zaporizhzhia and Kherson.

Europe and Ukraine may not like Putin’s opening bid, but ignoring what flexibility has emerged in Russia’s terms in recent months risks missing a real chance for peace. Putin’s seeming escalation in the skies over Ukraine and his willingness to begin serious negotiations are not mutually exclusive. In fact, if he is serious about talking, eeking out whatever military gains he can now would be a rational way to increase bargaining leverage.

In any case, delaying diplomacy and continuing to struggle on the battlefield until Putin puts down his weapons is likely to make things worse, not better, for Ukraine. The most favorable settlement available to Ukraine was the one it might have negotiated in April 2022 or November 2022. With its military currently on the ropes, the next best option is the one negotiated today. If Putin is indeed open to talking, even if just at the working level and if fighting continues at the same time, it is in Ukraine’s best interest to get on board.

Ultimately, it is Kyiv and Moscow who must reach an agreement but in addition to eschewing new sanctions and other futile tactics to force Putin into a ceasefire, the Trump administration can help push things along in three ways.

First, Washington can serve as convener, bringing teams from Moscow and Kyiv together and facilitating private dialogue between the two sides. In this role, Trump will have to avoid the temptation to insert himself directly while the necessarily slow process plays out. After all, Kyiv and Moscow have shown that given time and space they can reach a mutually agreeable endpoint. They almost succeeded in Istanbul in 2022 and can do so again.

Second, the United States can help bridge the demands made by each side, offering Ukraine carrots to make concessions easier and Russia incentives to reduce the demands on Ukraine. For example, promising Ukraine time-limited military assistance after a settlement or building strategic stockpiles of air defense and other munitions that Kyiv would receive in the event of renewed war would be sustainable ways to reassure Ukraine of its future security without compromising U.S. interests.

In the case of Russia, the Trump administration might offer to open discussions about the U.S. role in Europe’s long-term security architecture in return for more flexibility from Moscow on Ukraine’s own military capabilities. The Trump administration has already signaled an interest in pulling back from its role in Europe, so reductions in U.S. commitments on NATO’s eastern flank could be a win-win — achieving an administration priority while addressing Putin’s “root causes.” The promise of sanctions relief or other types of bilateral cooperation might also convince Russia to lessen what it requests from Ukraine.

Finally, the Trump administration can regulate European involvement in negotiations, acting as a buffer against what has been the continent’s unhelpful interference. So far, European leaders have encouraged Zelensky to stick to unreasonable goals, set unrealistic expectations, and criticized what progress has occurred. The latest “reassurance force” charade is more of the same, an exercise in fantasy that extends the war rather than ending it.

The United States continues to have significant leverage over Europe, and the Trump administration should not be afraid to use it to keep Brussels from scuttling future diplomacy. Trump should communicate to his European counterparts that meddling in ongoing talks is unwelcome and will come with consequences for the transatlantic relationship. At the same time, he can engage with Europe at a later point on how they can support Ukraine after an agreement is reached.

With his military forces advancing on the battlefield, Putin is unlikely to stop fighting in the immediate term. Still, he seems ready to at least think about the end of the war and to talk about the terms of a settlement. If Trump is serious about achieving peace, he shouldn’t let this window of opportunity pass.