The global order was already fragmenting before Donald Trump returned to the White House. But the upended “rules” of global economic and foreign policies have now reached a point of no return.

What has changed is not direction, but speed. Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney’s remarks in Davos last month — “Middle powers must act together, because if we’re not at the table, we’re on the menu” — captured the consequences of not acting quickly. And Carney is not alone in those fears.

Leaders around the world are increasingly moving from rhetorical warnings about the systemic risks of superpower dynamics to actively experimenting with new ways of navigating what Carney called “a rupture in the world order.”

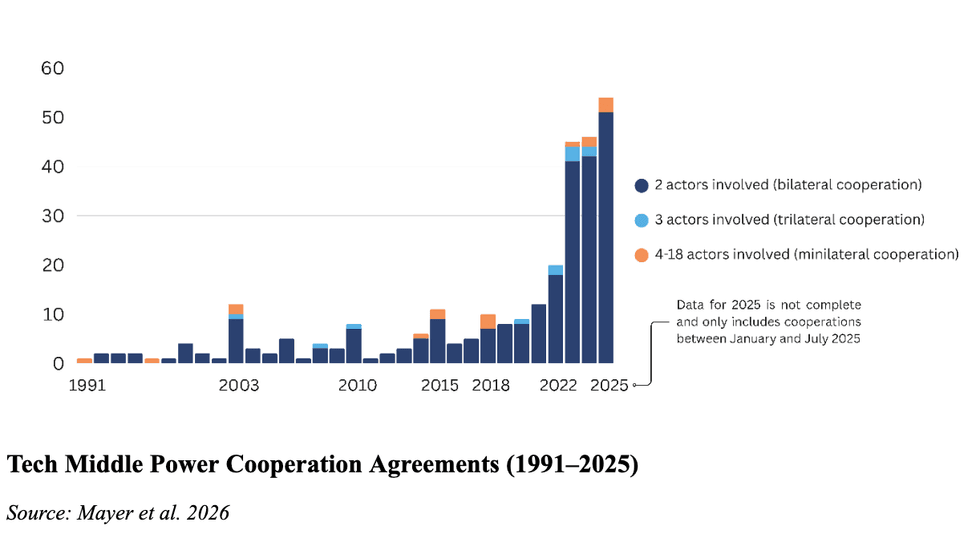

One such strategy is “workarounding,” a deliberate use of flexible, issue-specific cooperation among middle powers to create strategic space outside rigid U.S.-China alignments. This approach has gained traction over the past decade as great power competition intensified. It is now expanding as Washington’s policies inject further uncertainty into the global system.

This shift in practice offers several advantages for middle powers. Small, adaptive constellations, often cross-regional, can bypass growing volatility at the global level by excluding superpowers from cooperation. They preserve room for maneuver by diversifying partnerships. And they create space to shape outcomes on issues that matter for middle powers.

Unsurprisingly, examples of workarounding abound.

Forecasting a “messy” decade of transition, Singapore’s Prime Minister Lawrence Wong warned in October 2025 that U.S. policies were undermining global trade and common interests. Rather than relying on existing institutions, he called for building new trade connections and closer cooperation with like-minded partners. Countering unilateral tariffs, Wong argued, could not be done alone.

These ideas were quickly translated into action. Middle powers Singapore and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) joined together with 12 small states to roll out an adaptive, non-traditional project promoting open trade. Dubbed the Future of Investment and Trade Partnership (FITP), it includes Brunei, Chile, Costa Rica, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Morocco, New Zealand, Norway, Panama, Rwanda, Switzerland, and Uruguay. Its purpose is not to replace existing institutions, but to amplify the collective influence of its members through pragmatic coordination.

FITP-like arrangements and other agile platforms enable members to collaborate across selected trade and investment issues. Other workarounding tactics include strengthening supply chains, removing non-tariff trade barriers, facilitating investment and establishing rules around emerging technologies. These tactics are flexible, non-binding, and deliberately modular, making them attractive to middle powers adapting to an increasingly volatile environment.

One notable result of this experimentation is that middle powers are shifting from regional to cross-regional constellations, ranging from the Indo-Pacific to the Middle East, to Europe and beyond. This trend extends beyond trade. For example, the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) includes issues of technological interoperability and AI governance alongside digital trade rules.

Established in 2020 by Singapore, Chile, and New Zealand, DEPA’s appeal as a flexible alternative to traditional trade regimes is evident in the rapid expansion of its membership. South Korea joined in 2024, and Canada, Costa Rica, Peru, the UAE, El Salvador, and Ukraine have also formally applied.

Beyond preserving strategic space, workarounding enables middle powers to exert influence. In Latin America, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Bolivia are exploring coordination in lithium production to avoid being squeezed by dominant buyers such as the United States and China. Described as a potential “OPEC for lithium,” such cooperation symbolizes middle power efforts to translate resource endowments into collective leverage amid the global energy transition and technological competition.

Similar dynamics may soon emerge in Africa as competition over critical minerals intensifies.

Clearly, workarounding is becoming a core element of pragmatic statecraft among small states and middle powers. But this is true for larger middle powers as well. After facing a series of setbacks in 2025, including a sharp tariff hike imposed by the United States, India intensified efforts to diversify its trade relationships.

Expanding negotiations beyond traditional partners, New Delhi renewed its engagement with the Eurasian Economic Union, is pushing for a speedy deal with the Southern African Customs Union, and concluded a long-delayed trade agreement with the European Union in February 2026. This immediately accelerated the India-US trade deal that had been in a limbo for months. New agreements on trade, semiconductors, critical minerals and defense signed during German Chancellor Friedrich Merz’s recent state visit to India reinforce the capacity for workarounding to move the needle on some of the most turbulent geopolitical issues.

Taken together, these developments point to an evolving landscape of middle power statecraft that blends competition and cooperation. A Goldman Sachs report highlights the growing influence of geopolitical “swing states,” suggesting their ability to navigate superpower competition could help stabilize an increasingly fragmented order.

Another concept gaining traction is the “Fourth Pole.” This argument suggests that, alongside the United States, the European Union and China, there is room for a fourth pole comprising India, the Gulf States and other players across Asia, Africa, Southeast Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean. Linked by networks rather than formal alliances, these states could act as force multipliers, facilitating innovation, norm-setting, and strategic autonomy for themselves in a changing world.

In this sense, workarounding practices are living laboratories for new forms of statecraft, industrial policies and economic and science diplomacy. They expand the geographical reach of cooperation, connect public and private actors across regions, and embody the speed at which states are adapting to shifting political and security realities

Canadian Prime Minister Carney’s Davos statement, “We are in the midst of a rupture, not a transition,” demonstrates middle powers’ mindset has already shifted. For Washington, the implication is clear: it remains a central power, but no longer sets the agenda alone. How it engages with these middle power networks will shape whether workarounding complements U.S. strategy or bypasses it.

If ignored, workarounding may evolve in ways that gradually dilute American influence in the very systems it once anchored. Despite Trump’s bluster and hemispheric pretensions, cooperation between and among middle powers is a growing force to be reckoned with.