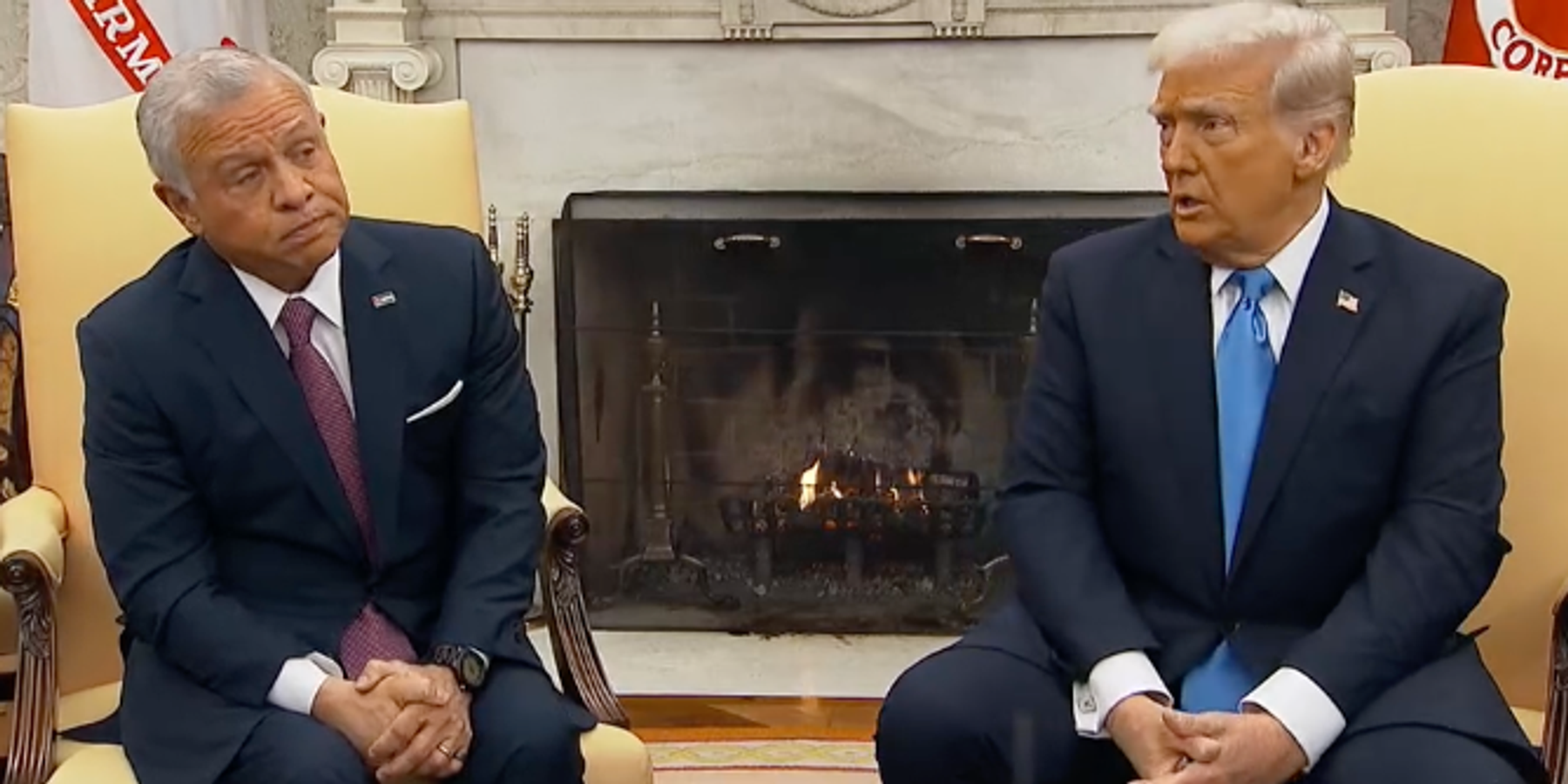

Jordan’s King Abdullah II just met with President Trump, and afterwards during a short press conference, deflected journalists’ questions about Trump’s insistence he accept Palestinian refugees from Gaza.

Abdullah said he would need to wait for other Arab leaders, including Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia and President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi of Egypt, before responding directly. President al-Sisi and other Arab leaders will meet in Cairo on February 27, ostensibly to propose an alternative to Trump’s plan to forcibly remove Palestinians from Gaza, which would be a war crime.

For his part, Trump asserted that Palestinians do not want to be in Gaza, would be happy to leave, and that they would not want to return. Trump did not address questions about how he would handle the fact that many Palestinians will refuse to leave. Sitting beside King Abdullah, who looked uncomfortable, Trump appeared to walk back his intention to force Jordan to accept Palestinians by withholding U.S. assistance to the kingdom, which he is already doing.

Jordan is in a difficult position, given the country’s reliance on U.S. support, which makes up about 10 percent of its national budget. Egypt similarly relies on U.S. assistance. Both countries began to receive significantly more financial support from the U.S. after signing peace treaties with Israel in 1994 and 1979, respectively.

When asked by Fox News’ Brett Beier about how he would convince Jordan and Egypt to take approximately a million Palestinian refugees each, Trump said, “We give them billions and billions of dollars a year.” Trump’s cut to foreign assistance includes the $1.45 billion the U.S. sends to Jordan annually (the only countries to which he did not cut assistance were Israel and Egypt). It is evident that from Trump’s perspective, Jordan owes the U.S., and so should be willing to take in Palestinian refugees.

Trump may not realize that by trying to strongarm King Abdullah into accepting Palestinians, he is not only risking the U.S.-Jordan relationship, but potentially the willingness of other Arab states to partner with America. Trump seems to believe that the U.S. sends military and humanitarian assistance to Jordan and other countries and receives little in return, rather than grasping that U.S. support to other countries has played a key role in maintaining U.S. leadership, and when forced to accept political suicide in order to support Trump’s regional agenda, countries like Jordan will increasingly seek other partners.

Moreover, Trump appears unaware that he is posing an existential threat to Abdullah’s rule and the stability of a major non-NATO ally. Jordan’s population is already approximately half Palestinian, due to previous Israeli expulsions of Palestinians in 1948 and 1967. Jordanians are seething over Israel’s war on Gaza. Ninety-four percent of the population are boycotting American goods as a result of U.S. support for Israel’s war on Gaza. Three attacks on the Israeli border or embassy have already occurred. If hundreds of thousands of new Palestinian refugees were forced into Jordan, the fragile status quo would likely collapse. Abdullah’s government could be overthrown, and given the success of the Muslim Brotherhood in September’s parliamentary election, the government most likely to replace it would not be interested in signing another peace treaty with Israel, or be willing to host U.S. troops.

In addition to the political instability that would result, Jordan simply does not have enough resources to take in additional refugees. Jordan lacks adequate water for its existing population, a scarcity made worse by Jordan’s refugee burden from previous conflicts, including the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the years of Syria’s brutal civil war. Jordan has remained a bastion of relative stability despite regional upheaval, due largely to the U.S. and Europe helping pay for Jordan to host refugees.

Despite this support, Jordan’s debt is already 90 percent of its GDP. Twenty-two percent of Jordan’s population are unemployed. When I visited last fall, interlocutors emphasized the economic distress faced by the majority of the population.

From Abdullah’s perspective, Jordan already does a lot for the U.S. At Washington’s urging, Jordan has maintained a peace treaty with Israel for the past 30 years, despite its deep unpopularity among the Jordanian population. Jordan hosts 15 different U.S. military installations and almost 4,000 American troops.

When I was last in Jordan in October to assess the impact of the war on Gaza, Iran fired missiles over Jordanian territory at Israel. The Jordanian military issued a statement that it had worked with the U.S. military to help shoot down some of the Iranian missiles. One of these even fell and killed a Jordanian. The next day, Jordanians expressed outrage: why was their government helping the U.S. to defend Israel, even at the expense of their own safety?

America’s partners from Saudi Arabia to the U.A.E. to Egypt have been willing to acquiesce to the U.S. vision for the Middle East — a vision that prioritizes the desires of Israel over the existence of Palestinians — because it served their own interests. With U.S. support and weapons, Arab autocrats have consolidated their hold on power. Their collaboration with the U.S. is predicated on the U.S. helping to keep them in power.

When the Obama administration failed to save Mubarak’s regime from the popular uprising that overthrew it in 2011, many Arab autocrats were shocked at what they saw as Obama’s betrayal of a key U.S. partner. If they observe Trump not only failing to support a U.S. partner but actively coercing him into a decision that could lead to his overthrow, rulers from Riyadh to Rabat may reconsider their partnership with the United States.

- How Trump’s ‘peace plan’ destabilizes Jordan ›

- Trump can't 'clean out' Gaza without destabilizing entire region ›

- Was Jordan's Muslim Brotherhood ban a bid to please Israel, Saudi? | Responsible Statecraft ›

- New US ambassador's charm offensive is backfiring in Jordan | Responsible Statecraft ›