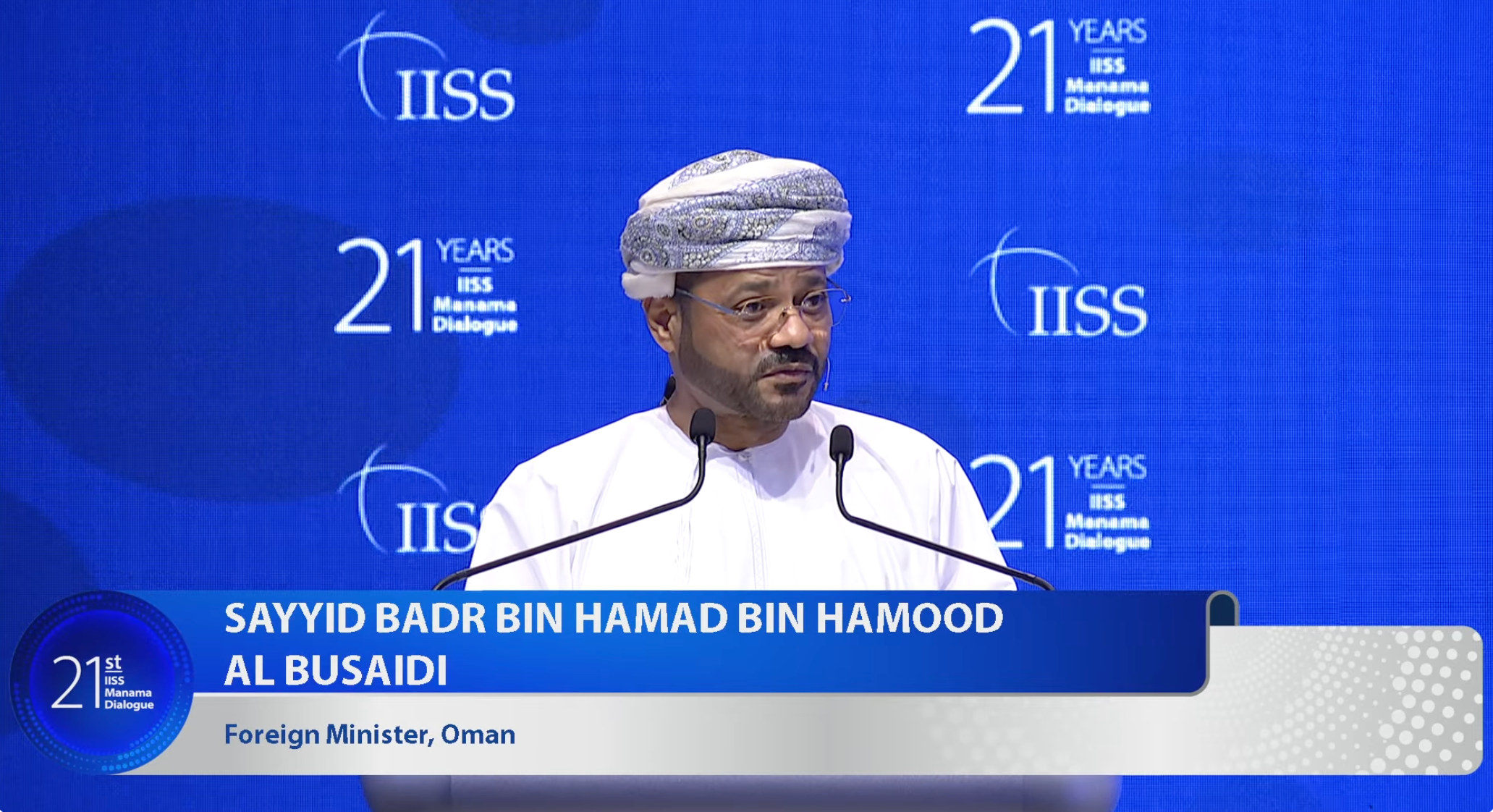

In a striking pivot, the foreign policy establishment of the Persian Gulf is no longer pointing its finger at Iran as the chief menace to Middle East stability — instead, it is now directing that accusation at Israel. That shift was laid bare by Badr al-Busaidi, the Omani Foreign Minister, who chose the Manama Dialogue in Bahrain last weekend — hosted by the UK think tank International Institute for Strategic Studies — as the venue to declare that, “We have long known that Israel, not Iran, is the prime source of insecurity in the region.”

This is more than just rhetoric. For nearly four decades, U.S. diplomats, strategists, and official doctrine have cast Iran as the epicenter of Middle Eastern instability, making this Arab reversal a serious alarm bell for Washington. If the region’s power brokers no longer see Iran as the chief source of turmoil, U.S. policy risks drifting badly out of sync, even as many Trump officials continue to recycle old talking points about Tehran’s unmatched role in fueling regional chaos.

From the Reagan era onward, U.S. foreign-policy discourse has portrayed Iran as the principal destabilizing force in the Middle East. During the Clinton administration, then-Secretary of State Warren Christopher famously declared that “wherever you look in the region, you see Iran’s evil hand” — a phrase that crystallized a bipartisan consensus enduring to this day.

This worldview took shape in the Clinton administration’s “dual containment” policy, which targeted both Iraq and Iran. The underlying logic was simple: Iran and Iraq were the sources of regional instability; Israel was the anchor of stability; and containing the former while supporting the latter would secure the Middle East and pave the way for peace. Ever since, the supposed need to contain Iran’s destabilization served as a central justification for sustaining American military hegemony in the Middle East.

The name of the policy has shifted over time, but its essence has endured — with the brief exception of the two years following the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, when Barack Obama’s administration temporarily paused Washington’s containment strategy. Even Donald Trump’s Abraham Accords, celebrated as a major policy innovation, ultimately reinforced the same premise: that Iran is the linchpin of regional disorder and that Arab states must align with Israel to contain Tehran.

It is not hard to see why an Arab foreign minister would not only reject Washington’s long-standing narrative but invert it — identifying Israel, not Iran, as the chief source of instability. In just the past two years, Israel has launched attacks on seven countries while carrying out what a U.N. commission has described as genocide in Gaza. It has reduced much of Gaza to rubble and devastated large parts of southern Lebanon. When Israeli forces struck Qatar — a key U.S. partner — GCC states could no longer deny that Israeli recklessness posed a direct threat to the entire region.

Omani officials argue that Washington’s own policies have helped produce this moment. The U.S. strategy of isolating and containing Iran, they contend, deepened regional polarization and foreclosed opportunities for de-escalation. Had Iran been integrated economically and politically into the region, tensions with the U.S. and Israel might have eased — while also diminishing Tehran’s threat to its Persian Gulf neighbors. Indeed, in his Manama speech, Al-Busaidi called for an inclusive regional security architecture — one that brings Iran, Iraq, and Yemen to the table rather than excluding them.

Crucially, Al-Busaidi emphasized that “we have long known” Israel, not Iran, is the main source of regional instability. This makes clear that his statement is not a reaction to events over the past two years alone, but a long‑held view that Arab officials are only now willing to express publicly.

When a senior GCC foreign minister — representing Oman, a country widely respected as a diplomatic interlocutor for both Iran and the U.S. — rejects the conventional framing in front of a largely American audience, the implications are profound.

This is not to suggest that GCC states no longer see Iran as a challenge or that its policies aren't or haven't been disruptive at times. A study I co-authored with journalist Matthew Petti in 2020 showed that Iran had been one of the most interventionist powers in the region, though its role had been supplanted by Turkey and the UAE since 2015. But if the GCC no longer regards it as the primary threat, its willingness to support U.S. Iran‑centric policies will decline. The Trump administration, pursuing Maximum Pressure 2.0, may discover it has few willing partners in the Gulf. Unless Washington recalibrates its approach, its policy thrust risks drifting sharply out of step with its GCC partners.

The Trump administration would be wise to heed Al‑Busaidi’s call for an inclusive regional security framework. Such an architecture would not only help stabilize the Middle East but also allow Washington to shift the burden of regional security onto local states rather than American service members. In short, it could provide a crucial pathway for the U.S. to responsibly reduce its military footprint and finally bring troops home from the region.

After 40 years during which Iran bore the lion’s share of blame, the Middle East is signaling a new epicenter of concern. The U.S. must take note — and treat this as an opportunity to retire Iran-first conceptions of instability that have served to keep the U.S. entangled in a region that several presidents in a row have declared no longer constitutes a vital region for U.S. national security.