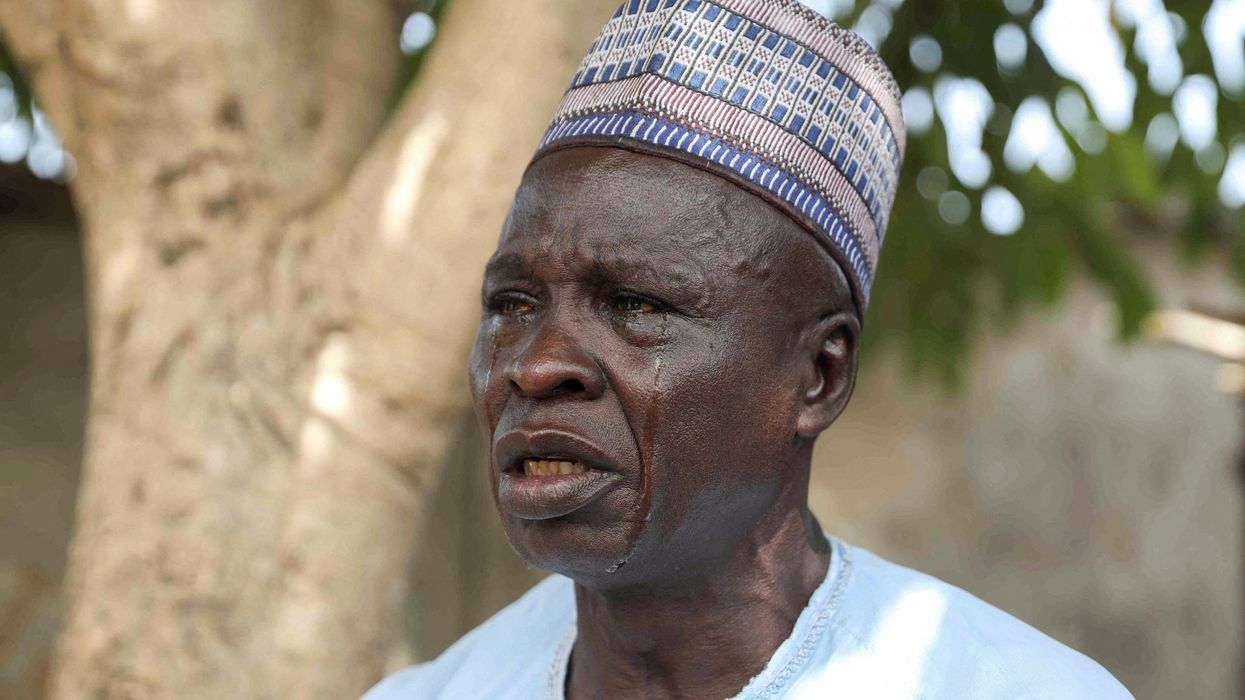

Amid the gruesome Gaza war, passions are running high throughout the Arab world. Huge Palestine solidarity protests have been occurring across the region, and this terrifies many ruling elites who fear the Palestinian issue.

They view it as dangerously destabilizing, and starting months ago, a handful of Arab states, including Egypt, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia, began clamping down on pro-Palestine activism in their own countries.

Such a crackdown in these Arab countries is no surprise and should be understood on two levels. The first applies to protests in these countries at a foundational level. The second is specific to the Palestinian issue.

Fear of political mobilization

Authoritarian regimes in general often suffer from legitimacy crises and thus see any grassroots activism and mobilization of citizens as potentially threatening. This is the case irrespective of what cause brings the people together. Most Arab governments want to co-opt and regulate such movements and prevent them from ever challenging regime-backed narratives and interests.

"Most Arab states are generally allergic to popular protests,” said Marina Calculli, a Columbia University research fellow in the Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies, in an interview with RS. “They fear that opening the public sphere and allowing protests of solidarity towards Palestinians could encourage protests against the government and their policies in other fields.”

Other experts agree. “Any sort of popular mobilization or activism that brings people together, either online or on the streets, is a threat to these authoritarian regimes,” Nader Hashemi, the director of the Prince Alwaleed Center for Christian-Muslim Understanding at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, told RS. “Arab states today do not like Palestinian nationalism because Palestinian nationalism is a source of popular mobilization on the Arab street,” he added.

“The Arab world has turned its citizens into consumers basically,” explained Rami G. Khouri, a distinguished public policy fellow at the American University of Beirut, in an interview with RS.

“You can consume anything you want. There are 25 different kinds of fried chicken which you can buy in most Arab capitals and that’s fine. That’s what the governments want is to have people spend their time, money, and thoughts on consumption. But anything that has to do with political power, public policy, and allocation of economic gains have to be controlled by the government,” he added.

Palestine exposes the regimes' vulnerabilities

As to the Palestinian question more specifically, it can tend to expose weakness on the part of many Arab governments. On one hand, Arab regimes must cater to public opinion by making mostly symbolic and token gestures in support of the Palestinian cause. On the other hand, no Arab state wants to confront Israel. For many of them, this has much to do with their relations with the United States on which they rely for security and, in some cases, as a source of critical financial assistance.

With each day that the Gaza war persists, the domestic pressures on these regimes increase, which is the main reason why these governments are unanimous in calling for a ceasefire in Gaza. It is not so much about the well-being of the Palestinians per se, as it is about maintaining the stability, legitimacy, and even survival of Arab regimes. “Palestine is a just cause,” said Ghada Oueiss, a Lebanese journalist, to RS.

“Yet Arab despots never saw it but from one angle: How can I protect my regime?”

The longer this war continues, there will be more Arab citizens asking obvious questions about why Arab states, which spend massive amounts of money on arms, are not giving so much as one bullet to the Palestinian resistance.

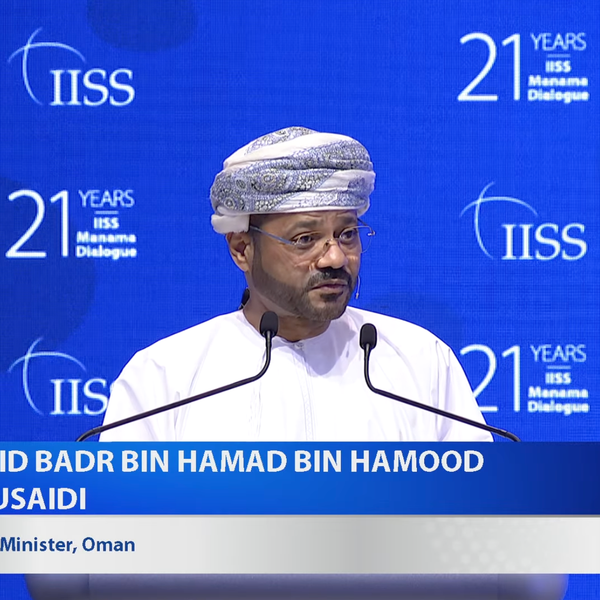

Such questions make these regimes extremely uncomfortable, particularly those Arab states that normalized diplomatic relations with Tel Aviv. At this particular moment, when societies across the MENA region react to what most Arabs and Muslims consider a genocide in Gaza, there is a sense of shame on the part of Arab governments that have worked with the West and Israel to essentially try to bury the Palestinian cause under the normalization accords.

“Most Arab regimes are fundamentally implicated in the attempt to suppress the Palestinian quest for freedom and normalize Israel’s occupation of Palestine, which they have long used as a bargaining chip to obtain concessions from Israel and especially the United States and European countries on areas such as security, energy, and commercial agreements,” according to Calculli, who says these regimes risk being seen as complicit in what is happening in Gaza today.

Also to consider are important historic factors relating to the Arab world’s Cold War-era politics and the rise of populist Arab nationalists, and later the Muslim Brotherhood, and how the Palestinian struggle was important to both.

“The Palestine protests are particularly disliked by governments because they have been exploited historically by the two forces that are most threatening to Arab governments, which are Islamist movements and Leftist movements,” according to Khouri.

“Even from the 1950s it was the Leftists who used the Palestine issue to rally support and challenge the governments,” he explained, “and more recently it was Islamists, so that gives them an extra resonance which governments don’t like.”

The Palestine issue is one that symbolizes a broader struggle for freedom and dignity, which strikes a chord in many Arabs, Muslims, and people of the Global South. For example, last month hundreds of Bahraini political prisoners chanted support for Palestine and waved Palestinian flags when they were released following a royal pardon.

This sense of solidarity between Palestinians and non-Palestinian Arabs is nothing new. “Your freedom is tied to our freedom and our freedom is tied to your freedom” is what Palestinian prisoners told Abdul-Hadi al-Khawaja, a Bahraini prisoner of conscience, in 2012 when he was on a hunger strike.

“The question of Palestine is a question of injustice, and that question of injustice is then interpreted by Arab masses as symbolizing a quest for justice across the board, which also includes criticizing the authoritarian regimes in the Arab world which are monumentally unjust,” Hashemi told RS.

He noted that many Arab governments deny their own citizens the basic right to self-determination within their own societies, which helps explain why ruling elites in these countries view the Palestinian cause as a threat and want to “quash and suffocate it.” Hashemi concluded, “What they prefer is a form of Palestinian nationalism that’s embodied in the politics of the Palestine Authority.”

- Is US helping to create new global jihadists? ›

- Despite official celebrations, Arab street still resents the Abraham Accords ›

- Forget 'peace,' did Abraham Accords set stage for Israel-Gaza conflict? ›

- Israel testing cold peace with Egypt | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Why Egypt can't criticize Israel for at least another two decades | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Egypt stepping out from Israel's shadow? It depends. | Responsible Statecraft ›