At 8:45 on the morning of October 16, 1962, President John F. Kennedy’s national security adviser McGeorge Bundy entered the White House residence with grave news for the president. Bundy, with a stack of photographs under his arm, informed the president that the CIA believed it had evidence the Soviets were constructing medium range ballistic missile bases near San Cristobal, Cuba.

The thirteen days of the Cuban Missile Crisis had begun.

It is frequently said (and it is no less true because of it) that the current crisis we now find ourselves in with nuclear armed Russia rivals the Cuban Missile Crisis. How and why that crisis came to a peaceful resolution owes itself to a number of factors that we believe are especially relevant today. Principally among those is the importance of strategic empathy in the formulation and practice of foreign affairs.

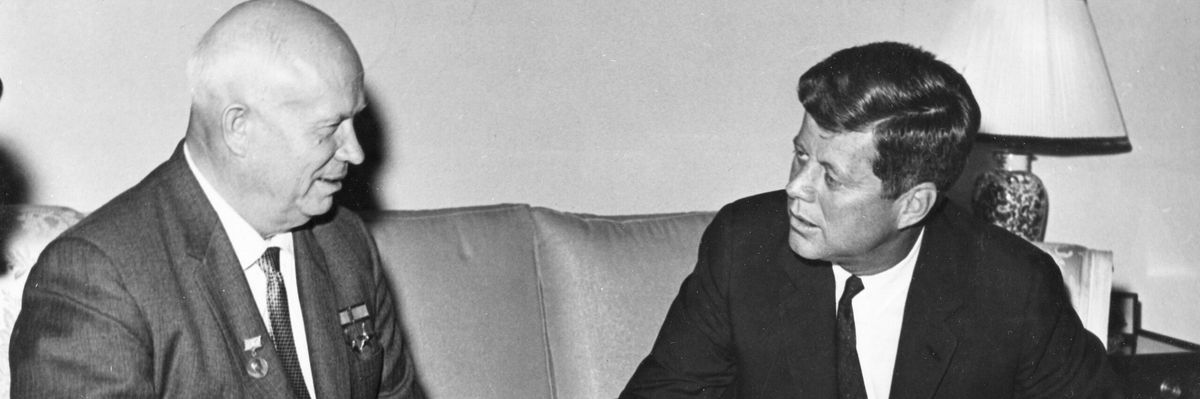

As the psychologist and former government official Ralph White has observed, “empathy is the great corrective for all forms of war promoting misperception. It means simply understanding the thoughts and feelings of others.” The ability of both Kennedy and Khrushchev to empathize with the position of the other enabled both countries, and the world, to weather the storm.

During the Cuban crisis, Kennedy was under intense pressure to act militarily, by striking the Soviet missile sites or invading Cuba, from the Joint Chiefs of Staff; members of the Executive Committee (ExComm) of the National Security Council (including, and especially, from his own vice president, Lyndon Johnson); and from congressional leaders, including Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman Richard Russell. But time and again, to the consternation of his hardline civilian and military advisers, Kennedy pulled back from the brink.

One of President Kennedy’s most controversial decisions during the thirteen day crisis was to allow the Soviet tanker, the Bucharest, proceed past the U.S. naval blockade.

According to Robert Kennedy’s posthumously published memoir of the crisis:

“Against the advice of many of his advisers and of the military he had decided to give Khrushchev more time. ‘We don’t want to push him into a precipitous action-give him time to consider. I don’t want to push him into a corner from which he cannot escape.’”

President Kennedy also wisely resisted near unanimous pressure from the ExComm to launch a retaliatory strike against the Soviet surface-to-air missile sites that were believed responsible for the downing and killing of American U2 pilot Rudolf Anderson, Jr. who was on a reconnaissance mission over Cuba on October 27.

Khrushchev likewise understood that Kennedy was under immense pressure to act by his military and national security apparatus. Thanks to a series of backchannel meetings between Robert Kennedy and the Soviet Ambassador to the United States, Anatoly Dobrynin, Khrushchev became aware of the pressures acting on the U.S. president.

In his memoirs, Khrushchev recalls Robert Kennedy’s warning to the Soviet Ambassador: “The military is putting great pressure on him, insisting on military actions against Cuba…Even if he doesn’t want or desire a war, something irreversible could occur against his will. If the situation continues much longer, the President is not sure that the military will not overthrow him and seize power.”

According to Khrushchev’s son Sergei, the Soviet leader told his foreign minister, Andrei Gromyko, that he saw Kennedy’s backchannel message as a call for “help.”

“Yes, help,” Khrushchev told Gromyko. “We have a common cause, to save the world from those pushing us toward war.”

The crisis was ultimately resolved with an agreement that the United States would not invade Cuba in exchange for the removal of the offending Soviet missiles. A further understanding, kept secret at the time, was made that the United States would remove NATO’s Jupiter missiles in Turkey, which were viewed in the same way by the Soviet leadership as the Kennedy administration viewed the Soviet missiles in Cuba. The Soviets acquiescence in keeping the latter part of the agreement quiet, so as to allow the United States not to appear as though it was selling out a NATO ally, is another example of how strategic empathy played a role in ending the crisis.

Robert Kennedy noted in the years after the crisis, that the members of the ExComm who participated in the discussions, in his view, “were bright and energetic people. We had perhaps amongst the most able in the country, and if any one of half a dozen of them were President the world would have been very likely plunged in a catastrophic war.”

Taken together, the embrace of strategic empathy by Kennedy and Khrushchev paved the way for the peaceful resolution of the most dangerous crisis of the Cold War.

The lessons are clear. Yet worryingly, the question remains whether the current American and Russian leadership are inclined to learn from them.