Systemic crises are illuminating for lots of interesting reasons. At the top of the list are the images of ourselves, reflected back at us in the ubiquitous digital media that spans the globe.

In this case, the crisis is indeed systemic — all parts of the globe are affected in one way or another and must address (or not) the challenges posed by the COVID-19. The images thus tell us about the broader global system that we are a part of.

The crisis presents us with a mirror through which to view the structure of global politics and the assumptions around which that structure has taken form. A traditional “realist” way of looking at the international system is to think of the strength and power of states relative to one another. Traditional measures of the system like GDP and size/strength of a military are one way to determine which state(s) wield power.

These measures have delivered the popular metaphor as the “return of great power competition” as a set of organizing ideas around which to think about the rise of China and the challenge this poses to America’s global position.

Some observers would include Russia in this mix as well, and it certainly true that Putin has positioned Russia as revisionist state seeking to enhance its position relative to other states. Despite its nuclear arsenal, however, it is hard to argue that Russia is in any sense a “great power.” That leaves two primary states as the major powers — at least by traditional measures: the United States and China.

Yet the two supposed “great power” states have stumbled through the COVID crisis for different reasons, revealing their intrinsic sources of weakness that run counter to the popularly accepted measures of what constitutes strength relative to other states.

The image being reflected back to us in the COVID pandemic is a jarring one: states with a strong social compact have done better that those where that compact is frayed, or, in certain cases, non-existent. Intrinsic strength as reflected in the relationships of the citizen to the state and strength and legitimacy of governing institutions may be a far greater indicator of international power and resiliency than our usual metrics of national strength.

The two states thought to be at the top of the global heap have left a trail of wreckage behind them a mile wide and a mile deep. China’s initial response to the pandemic was first to pretend that nothing had happened. Then it tried to silence those few who kept warning the ruling Communist Party and world of the building threat. Rather than take strong, decisive action at the outset — the regime circled the wagons until that position finally became untenable. This is hardly surprising from a regime that lives with the debilitating legacy of the slaughter of Mao’s cultural revolution and today’s gulag in Western China where it is keeping over a million Muslims under lock and key replete with machine guns and guard towers.

America’s stumbles are the product of a quarter century’s war on the federal government by the Republican Party, first launched in the Reagan era and then continued in earnest with Newt Gingrich’s Contract With America. The Republicans’ war has ground down America’s national institutions and sought to destroy the relationship between the citizen and the state as the party shoved its racist, social Darwinist philosophy down the throats of the nations’ citizens. All the while the top 0.1 percent lined their pockets with their inflated stock prices and a rigged tax code, leaving the vanishing middle class to pile up credit card debt in the vain pursuit of the American dream as their wages stagnated.

The Democrats are not blameless in the erosion of public institutions. The corporate centrism of the Clinton and Obama administrations muted the party’s response to the Republican assault on government. Moreover, both presidents helped themselves to the corporate funding troughs that inevitably led to plans, programs, and policies that benefited these benefactors. Clinton even sold access to the White House sleeping quarters to his favored corporate backers. Sen. Bernie Sanders consistently soldiered on mostly alone in decrying the erosion of public institutions, and has lately been joined by a younger generation of Democrats like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez that may finally reposition the party to favor the interests of the many instead of the favored few.

The ascent of Trump says less about him, but speaks volumes to the success of Republican efforts, as 63 million Americans cast their vote for him in the last election. As of this writing, more than 100,000 deaths (and counting) now litter the Union as a monument to the Republican campaign to break what had once been a vibrant social compact. That compact today lies in tatters, with the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affecting the poor, minorities, and the elderly.

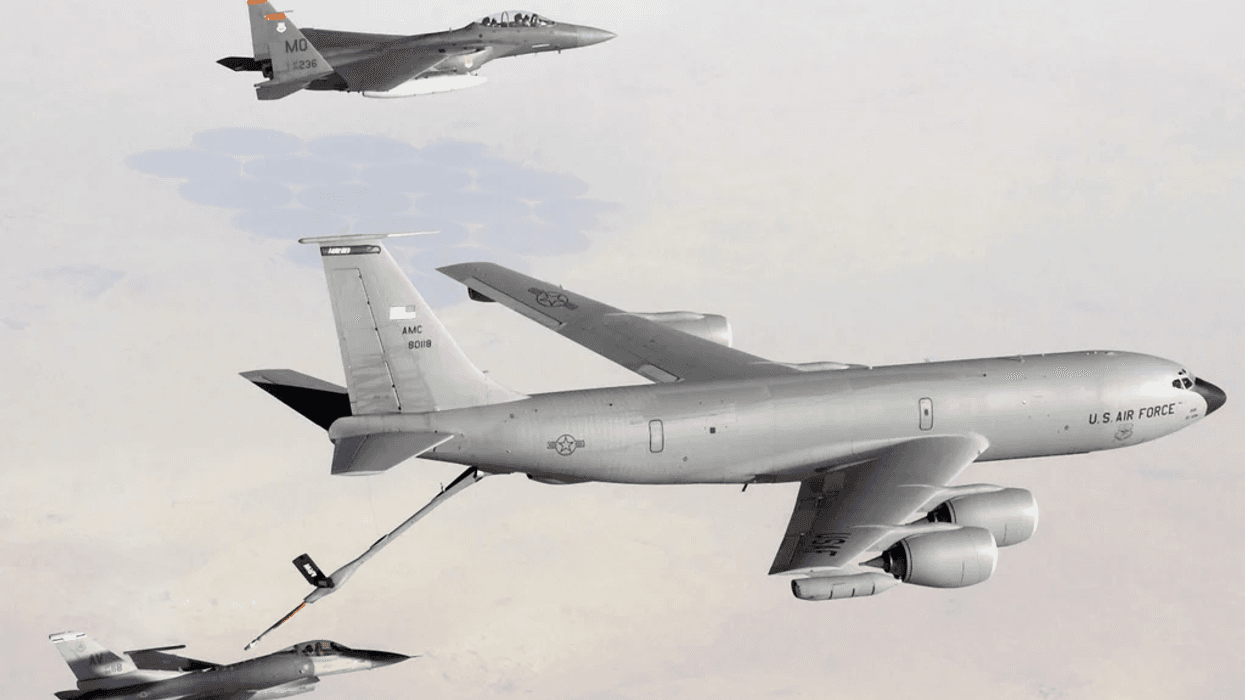

While true that America still has by far the largest defense budget in the world, can anyone really argue based on its response to the pandemic that the United States today exhibits the power of a state that has been at the top of the international heap going back nearly seven decades? America’s federal government today has declined to protect its citizens at home and is AWOL on the global stage in the crisis.

In contrast to China and the United States, states generally thought to be somewhat lower on the totem pole of international “power” have done better because of their strong social compact. At the top of this list must lie Germany, where Chancellor Angela Merkel warned her citizens early and often of what was coming and took decisive steps to address the threat.

Today, Merkel and French President Emanuel Macron are taking the lead on trying to orchestrate an EU-wide set of pandemic relief measures to, among other things, preserve the European Union –—a union of states built on the assumption of a strong common social compact that clearly spells out the two-way street between the citizen and the state. There seems to be little doubt that the other EU states will successfully pick themselves up and shoulder on as a result of their strong social compact. The EU may emerge from the crisis once more as a global force for leadership.

Two other examples of “strength” in the pandemic are exhibited by New Zealand and Canada, both of which have strong and charismatic national leaders to help their countries navigate their way through the crisis. The successes of these two states contrasts with Iran, which, like China, is a hollowed out, corrupt regime, that has lost the allegiance of its people.

What does all this mean for the structure of international politics? It suggests that this structure is a good deal more complex than generally believed. GDP and strong militaries only go so far and are incomplete as sources of power influence around the world. National and global power is a far more dynamic phenomena than we think.

At the center of all national power sits the social compact. Those with a strong one have the chance to survive and flourish; whereas those with a weak one are always under threat. China’s and Iran’s leaders will always be nervously looking over their shoulders, whereas Merkel and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau will eventually give way to new, responsible leaders to take the helm of government.

The wild card here remains the United States. The future of the country and its direction is up for grabs and it’s entirely possible that what remains of the social compact in America will burst asunder. Should this happen, America’s descent into the lower reaches of the international order will be swift and steep.