Having spent the past decade telling the British public that Russia poses the biggest ‘immediate threat’ to the United Kingdom, the idea that Britain should get ready to fight China is idiotic and irresponsible.

During a visit to Australia to join HMS Prince of Wales, which is currently leading Carrier Strike Group 25 to Asia, UK Defense Secretary John Healey implied that the UK might be willing to fight China in the Pacific over Taiwan. “If we have to fight, as we have done in the past, Australia and the UK are nations that will fight together. We exercise together and by exercising together and being more ready to fight, we deter better together.”

Rather than staying silent on military engagement over Taiwan, as UK governments have tended to do, Healey is trying to position Britain’s military forces as a deterrent to a resurgent China. This is deluded, and not just because the UK has shown itself unwilling to fight Russia directly over Ukraine.

Russia, as it were, is considered much more of a “threat” to European security than China. But even with Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s pledge of increasing defense spending to 5% of GDP by 2035 – and it is questionable whether this is affordable given the UK’s fiscal constraints – Britain most certainly isn’t big enough to fight both China and Russia, even if it wanted to.

Indeed, one of the arguments in favor of the U.S. pressuring Europe to foot the bill for ongoing war with Russia in Ukraine, is to allow America to refocus its energies in the Indo-Pacific region. An often and, in my view, distasteful mantra advanced by even the most hawkish US politicians on Russia, is that Ukrainian troops are fighting so U.S. troops don’t have to.

Healey’s comments display a worrying lack of strategic focus. The recent UK Strategic Defence Review (SDR) committed British naval forces heavily to the creation of an Atlantic Bastion designed to secure the North Atlantic from the growing threat of Russia’s rapidly expanding sub-surface fleet. Since 2011 alone, the Russian navy has taken delivery of 27 new submarines with more under construction.

At best, the SDR sets a target for the building of up to 12 new attack submarines to replace the five Astute class submarines currently in service, two of which are in refit. Any new vessels wouldn’t arrive at the earliest until the late 2030s. It also envisions a complex system of ocean sensors and uncrewed sub-surface assets to counter Russian submarines. Simply securing the Atlantic from a rapidly rising Russian threat will require extensive cooperation with European navies, in particular with France, Germany and Norway.

Even with a replenished fleet, UK naval power still won’t be sufficient to have global impact. The Carrier Strike Group 25, currently in the Pacific, has deployed a significant chunk of available naval assets: one carrier, one destroyer, one frigate, and one attack submarine; that’s right, all of four vessels.

As I have said before, the Chinese won’t be worried by this. China currently boasts at least 234 vessels, which is larger than the U.S. fleet, having outstripped American warship production by a significant margin since 2010. While the Chinese fleet is thought to be deficient in some key capabilities, such as aircraft carriers, larger fleets have won “25 out of 28 historical wars.”

Admittedly, one of three victories in which an outnumbered fleet prevailed was the Battle of Trafalgar where the Royal Navy pitted itself against France and Spain off the coast of Cadiz. Admiral Horatio Nelson had at his disposal 27 ships of the line and 4 frigates. This compares with the modern Royal Navy which, not including submarines, which didn’t exist in 1805, has 24 blue-water fighting vessels, including aircraft carriers, destroyers, frigates and mine counter-measures vessels.

The idea that, even in its entirety, this can deter China is a fantasy. Of course, any British and Australian military engagement in Taiwan would be under the command of a U.S. admiral as part of a fleet possibly supplemented by those Asian countries that might be willing to join the fight, possibly including Japan and South Korea.

A doomsday scenario of a World War III in the Pacific would draw much of the Royal Navy away from British shores, leaving our country even more exposed to Russia. So, while Healey’s hawkish comments might play well with breathless Western journalists at a presser on the deck of a British aircraft carrier docked in Darwin, they make no sense in the real world.

And, in any case, they make the defense secretary appear tone deaf and out of touch given the diplomatic pivot towards China that has taken place under Starmer’s government.

To his credit, the prime minister has sought to position Sino-British relations somewhere between the naivete of former Prime Minister David Cameron’s unpopular “golden era” and the aggressively Sinophobic policies adopted by Prime Minister Theresa May and her successors. That has led to unprecedented political engagement by UK ministers since the end of 2024, including visits by the foreign secretary and chancellor of the exchequer, chief of the defense staff and, most recently, the national security adviser.

In the face of intense media scrutiny of any moves that signal a softening of the UK’s stance towards China, the Labour government is trying to pull off the impossible. Attract much- needed Chinese investment into Britain while keeping Chinese hands off of sensitive industries and critical national infrastructure. Disagree in private about issues around democracy in Hong Kong and Uighur rights in Xinjiang, while reopening dormant areas of economic and financial cooperation.

Starmer met Xi Jinping at the G20 Summit in Brazil and is planning to visit Beijing later this year.

Of course, the biggest challenge Starmer faces on China is in trying to boost economic and trade relations at the same time he attempts to do the same with the U.S. and the European Union, without making any trade-offs along the way.

And therein lies the true vacuity of Healey’s comments. They may play well with AUKUS allies but will be understood as provocative in Beijing. This episode offers a healthy reminder that Britain will struggle to be friends with everyone, while looking to pick fights around the globe.

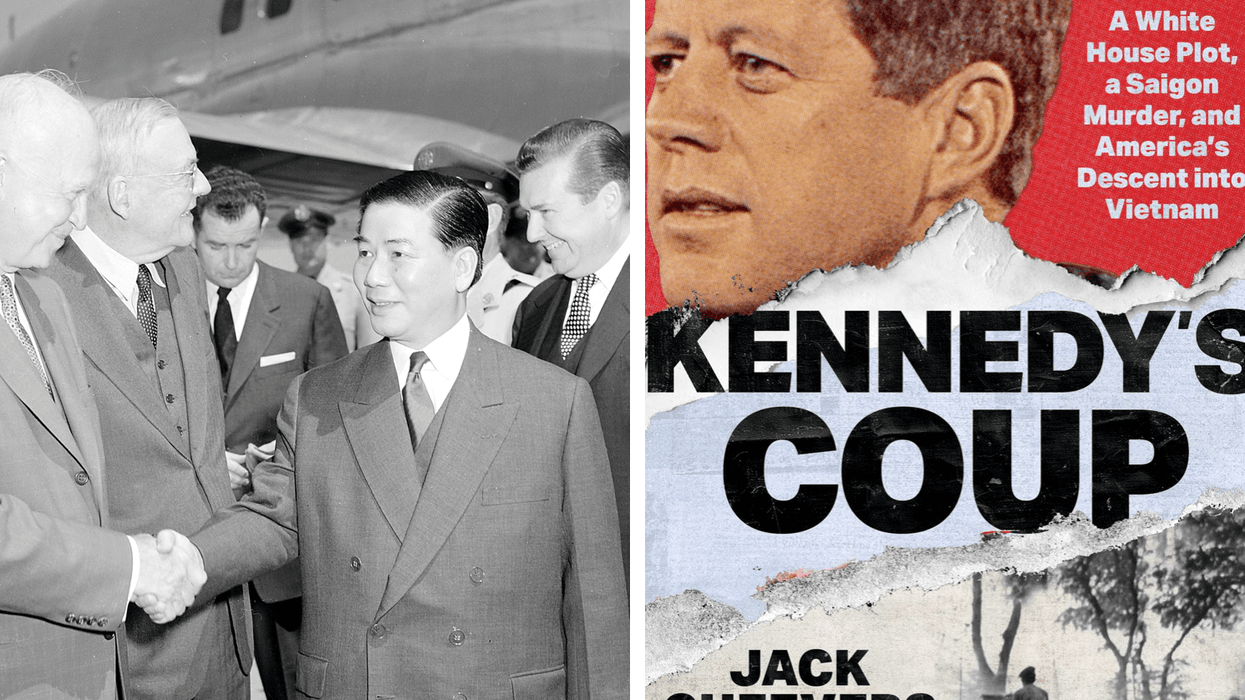

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)