While the United States has its hands full with conflicts in Europe and the Middle East, Latin America may become a region of greater focus for the incoming Trump administration. The region, sometimes derided by policymakers as the “United States’ backyard,” was hardly brought up directly by Donald Trump, Joe Biden or Kamala Harris on the campaign trail. But issues that were at the center of the election, such as immigration, tariffs and economic policy, are likely to shape how P resident-elect Trump engages with leaders of the Americas, especially newly elected president Claudia Sheinbaum in Mexico.

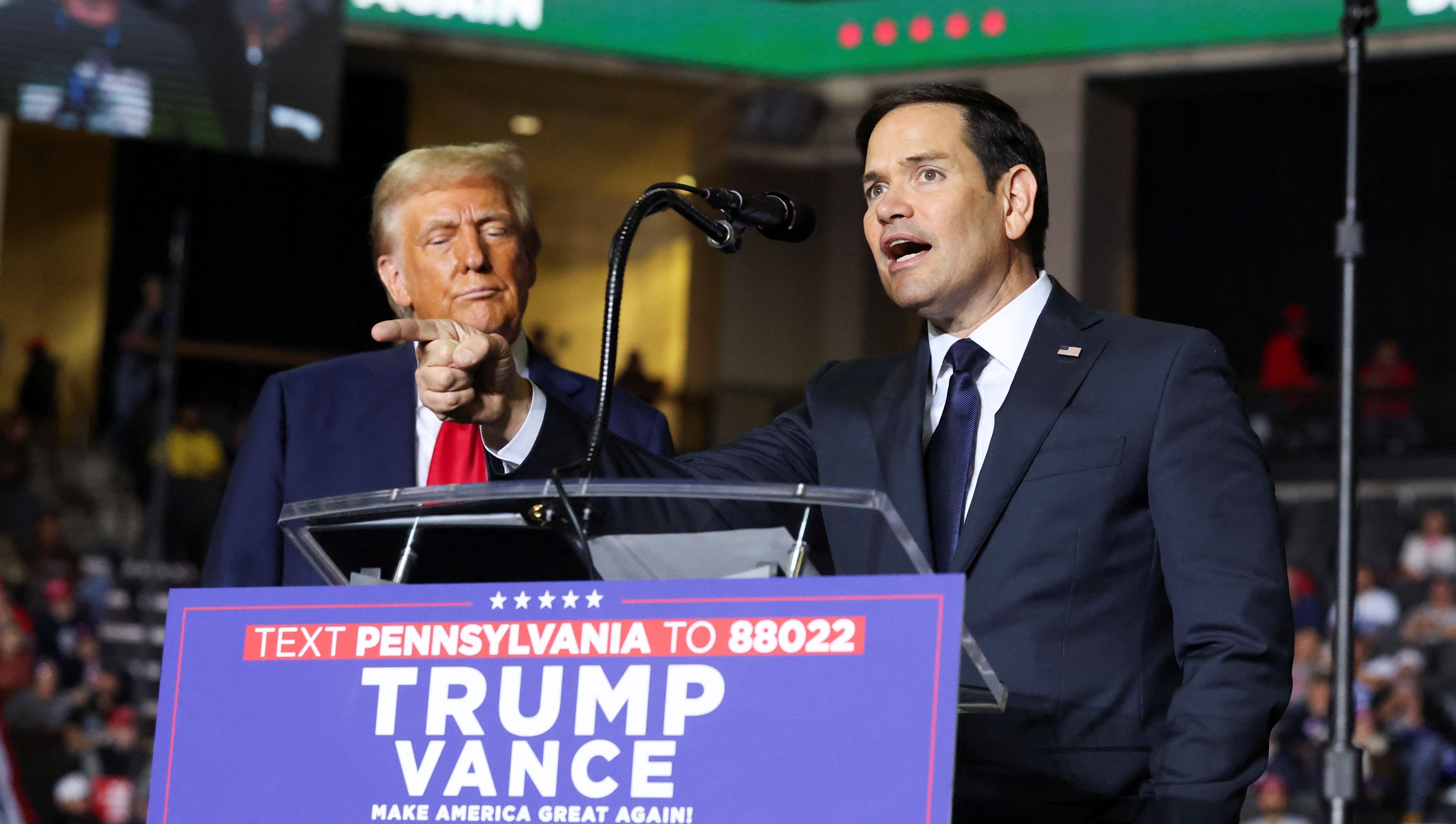

If Trump’s first cabinet picks are any indication of his policy toward Latin America, figures like Florida Senator Marco Rubio and Florida Rep. Michael Waltz, who have been nominated as secretary of state and national security adviser, respectively, could be a sign of a harsher posture, especially as U.S. competition with China plays out in the region .

A more aggressive posture?

Dr. Juan Gabriel Tokatlian, an expert in international relations at Universidad Torcuato Di Tella in Buenos Aires, Argentina, argues that Trump’s new term may bring a reassertion of the Monroe Doctrine, a 201-year-old policy that served as the basis for some of Washington’s more aggressive interventions in Latin America from the Mexican-American and Spanish-American wars in the 19th century to through the end of the Cold War. Tokatlian told Responsible Statecraft that he sees figures like Rubio using China’s advances in Latin America to revive the policy.

“There are signals, at least, …that this may be a rehearsal of the Monroe Doctrine at least in terms of positioning of the United States. Marco Rubio… has a very strong anti-Cuban, anti-Nicaraguan, anti-Venezuelan, but also anti-Petro and anti-Lula position,” he said in reference to the current presidents of Colombia and Brazil. “This all together in the context of what he sees as a growing challenge of a malign foreign power, … China.”

Rubio has been a champion of some of Washington’s most aggressive policies in Latin America. He has argued in defense of the 62-year-old U.S. trade embargo on Cuba , introduced a bill to prohibit Cuba’s removal from the U.S. State Sponsors of Terrorism List, and promoted Trump’s decision to impose “maximum pressure” sanctions against Venezuela and as part of a larger effort to achieve regime change there . He has also argued at length that China poses a “rising threat” in Latin America on the ideological, economic, and military fronts,

While it cannot be denied that China is advancing in the region — as the recent construction of a Chinese megaport in Peru demonstrates — the U.S. military footprint dwarfs any purport ed threat that China’s military presence may pose. As for China’s economic advances, Tokatlian argues that years of the United States offering little to nothing of value to Latin American countries have driven them to look more to trade with China.

“For years the United States did nothing, and so those countries decided to go to the best of their possibilities,” Tokatlian said. This point was demonstrated at the recent G20 Summit in Rio de Janeiro when China unveiled the $1.3 billion megaport in a remote fishing town just 37 miles outside of Lima. In contrast, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken boasted that the U.S. is “building a new passenger train line” in Lima. In reality, all the U.S. did was transfer a fleet of retired diesel trains.

Waltz shares much of Rubio’s focus on Latin America and has also promoted aggressive positions in the past. In 2021, he co-wrote a letter to the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations calling on his colleagues to reject Biden administration nominees who “refuse to assure tough stances on Cuba & Venezuela regimes.” Waltz has also argued that China’s advances in Latin America pose a military threat to the United States.

A focus on Mexico

Cuba, Venezuela and China may be the biggest targets of hawkish policies in Latin America, but perhaps the bellwether for what Trump’s policies will look like is Mexico where he will negotiate with leftwing President Claudia Sheinbaum. Last year the country replaced China as Washington’s biggest trading partner, making the U.S.-Mexico relationship a priority. The country, in particular its role in U.S. immigration policy, has been a consistent focus of Trump’s political career and was a focal point of his presidential campaign .

During Trump’s last term, then-Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador agreed, under threat of tariffs, to enforce U.S. border policies to greatly restrict migration from Central America. U.S.-Mexico relations will also be shaped by Trump, with the upcoming renegotiation of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA).

Aileen Teague, a nonresident fellow at the Quincy Institute who teaches the history of U.S.-Mexico and Latin America relations at Texas A&M University , anticipates that Trump’s negotiations with Mexico may cause friction in the relationship.

“Issues surrounding security, migration, and the economy are likely to be contentious as Trump, I believe, is unlikely to back away from many of his campaign promises,” she told RS in an email exchange.

“ Trump will increase pressure on Mexico to reduce migration and the drug trade, using the threat of tariffs and the looming revision of the USMCA (and potential consequences on the Mexican economy) to force Mexican action. This is significant,” she stressed. “ With Trump's campaign pledges to impose steep tariffs on Mexican goods, the value of the peso fell on election night (though has since recovered), indicating that investors are anticipating what Trump’s actions will look like and how that will affect economic relations.”

Teague added that Sheinbaum might bring her own demands into negotiations that could cause tension with Trump.

“She could take a more principled stance on some of these issues like crime or migration with a more nationalistic posture, which Trump might not respond well to,” Teague added. “She has suggested Mexico will not bow to U.S. demands over immigration issues.”

On Mexico, Trump’s cabinet picks again signal that the administration may engage aggressively. Waltz, for example, ignited an interventionist frenzy in the Republican Party last year when lawmakers and presidential primary candidates called for U.S. military action in Mexico. He co-authored legislation for the Authorization for Use of Military Force against Mexican Cartels.

While calls for military intervention in Mexico have largely died down, Waltz once again proposed extreme measures during a FOX News Interview in October, in which he argued that the United States should deploy special forces to Mexico to fight the cartels. Waltz cited the deployment of U.S. Green Berets in Colombia as a successful example of this policy. Critics of the U.S. policy known as Plan Colombia highlight how it failed to reduce cocaine production in Colombia while fuelling an uptick in civilian casualties in the drug war and human rights abuses . The 2008 Merida Initiative, a security cooperation agreement between the United States, Mexico and Central American countries, resulted in similar failures.

Despite the calls for military action by figures like Waltz, however, Teague has doubts about the likelihood of such a policy defining U.S.-Mexico relations during a second Trump administration.

“I could see the Trump administration taking a firmer, more militarized stance in the initial days of his presidency, but I don’t believe such an approach is sustainable,” Teague said.

Rubio, for his part, has said that he would be willing to deploy U.S. troops to Mexico to combat drug cartels, but emphasized “it has to be in coordination with the [Mexican] armed forces and the Mexican police force.”

Of course, Latin America is not a homogenous region. Important countries in the Southern Hemisphere have undergone unprecedented shifts to both the right and the left in recent years. How the different leaders engage with the United States must also be considered, and they may not all have the same approach or same priorities.

But if the past is precedent, and if personnel is policy, U.S. policy toward Latin America may be easier to predict. The next few years could bring a return to economic threats and bombastic rhetoric as ways to address complex issues ranging from drug trafficking, immigration and growing Chinese influence.

- Why is Latin America so pro-Palestine? ›

- Biden's Cuba policy is stuck on Trump's autopilot ›

- The elusive Chinese boogeyman in Latin America ›

- Rubio pushes for ‘bold diplomacy’ for Ukraine, confrontation with China | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Honduras threatens to boot US Military from base | Responsible Statecraft ›

- What Rubio said about multipolarity should get more attention | Responsible Statecraft ›

- The absolute wrong way to deploy US military on the border | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Trump's Latin American sticks could end up stuck in his spokes | Responsible Statecraft ›

- What awaits Marco Rubio in the Caribbean | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Reports: Trump to fire embattled hawk Mike Waltz from White House | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Former Air Force commando takes top LatAm job at NSC | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Trump doubles down on strikes against alleged smugglers in Caribbean | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Trump poised to decertify Colombia | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Rubio sparks diplomatic storm before Americas summit | Responsible Statecraft ›