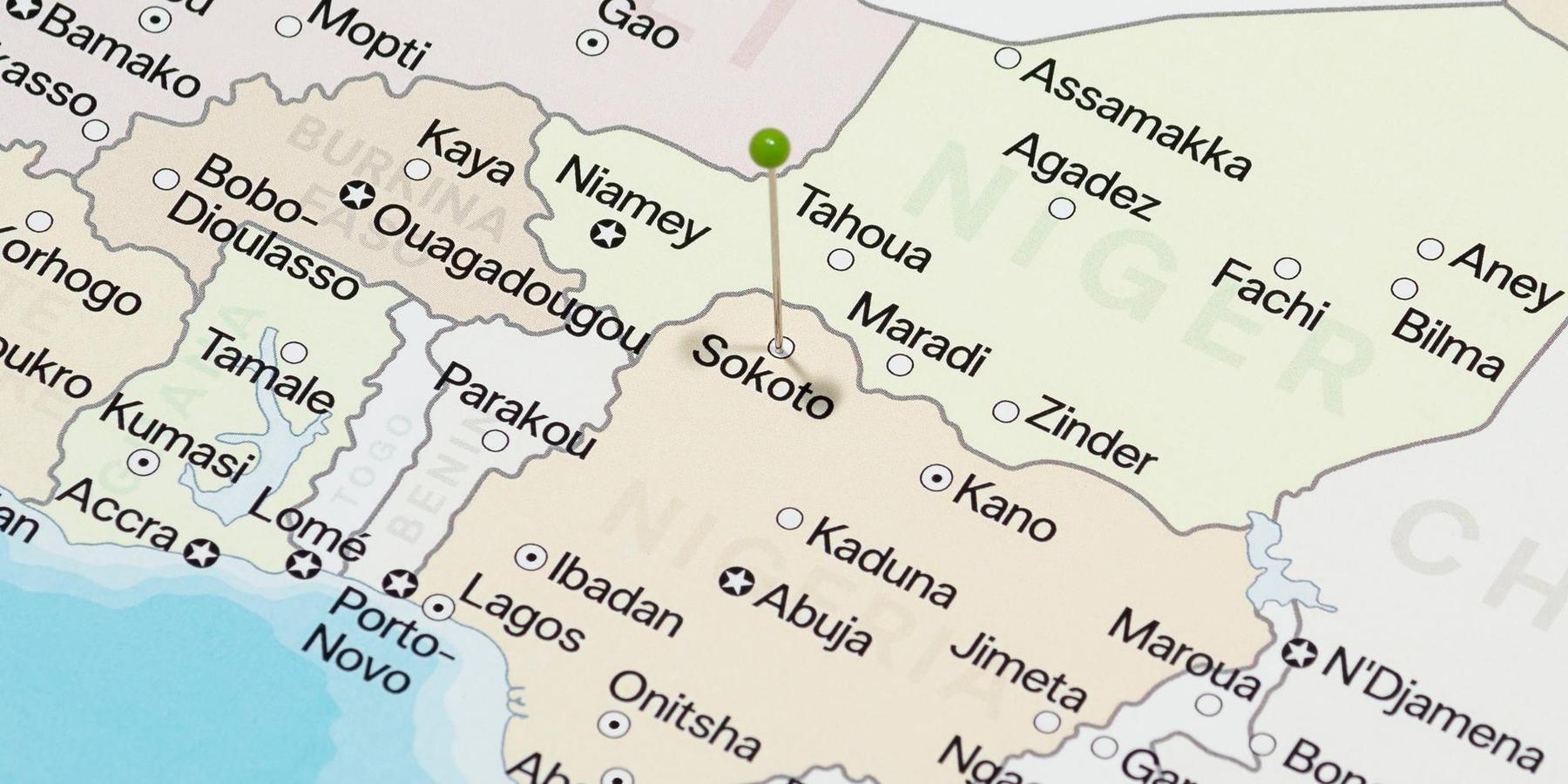

For the first time since President Trump publicly excoriated Nigeria’s government for allegedly condoning a Christian genocide, Washington made good on its threat of military action on Christmas Day when U.S. forces conducted airstrikes against two alleged major positions of the Islamic State (IS-Sahel) in northwestern Sokoto state.

According to several sources familiar with the operation, the airstrike involved at least 16 GPS-guided munitions launched from the Navy destroyer, USS Paul Ignatius, stationed in the Gulf of Guinea. Debris from unexpended munition consistent with Tomahawk cruise missile components have been recovered in the village of Jabo, Sokoto state, as well nearly 600 miles away in Offa in Kwara state.

No civilian casualties were reported in both areas, although there were damages to buildings in Offa.

It is the first direct U.S. airstrike on Nigeria’s soil — a West African oil-producing giant that Washington has often considered a crucial ally in the turbulent Sahel region. It is also the sixth country, following closely behind Iran, Iraq, Somalia, Syria and Yemen, where Trump has authorized airstrikes this year alone.

The U.S airstrike came a day after a bomb ripped through a mosque in Maiduguri in northeastern Nigeria, leaving at least five people dead and dozens injured. In a post on social media shortly after the airstrike, Trump identified the target as “ISIS Terrorist scum, who have been targeting and viciously killing, primarily, innocent Christians, at levels not seen for many years, and even Centuries!” He concluded by wishing everyone Merry Christmas “including the dead Terrorists.” The U.S. Africa Command (Africom) also said that “multiple Isis terrorists were killed” in strikes on camps in Sokoto.

But days after, there is still no official confirmation by the Nigerian government that any terrorists were killed. Many Nigerians are also asking: Why Sokoto? “The airstrike raises more questions than it resolves”, says Stephen Adewale, a Professor of History at the Obafemi Awolowo University (OAU) in Nigeria.

A predominantly Muslim state, Sokoto is far removed from the Middle Belt where Christian communities have suffered the most sustained and large-scale violence in recent years in complex conflicts involving armed groups, criminal gangs, and communal tensions. The state is also far removed from the epicenter of the jihadist insurgency in Borno State in the northeast and the Lake Chad Basin area where the more prominent terrorist groups, Boko Haram (JAS) and Islamic State of West Africa Province (ISWAP) have built a base. Except for a network of notorious bandit groups that abduct civilians for ransom, Sokoto, whose population in any case is overwhelmingly Muslim, has not experienced the same scale of jihadist violence as other states in the region.

According to Nigeria’s government, foreign ISIS elements have been infiltrating Sokoto State from the Sahel region and, in collaboration with local affiliates, are using locations in the state as assembly and staging grounds to plan and execute large-scale terrorist attacks within Nigerian territory. But the only jihadist group in the state is the little-known Lakurawa, a shadowy Sunni group that came to prominence early this year when Nigeria government designated it a terrorist organization. The group started as a vigilante outfit invited from neighboring Sahel countries by local communities in northwestern Nigeria to protect them from bandits before evolving into a jihadist movement preaching and enforcing strict Islamist rules across villages along the borders of Sokoto and Kebbi States.

Despite U.S and Nigeria’s official statement saying the airstrikes targeted “Islamic state enclaves” in Sokoto State, Lakuruwa’s international affiliation is still an unresolved controversy with some jihadist experts claiming they are Al-Qaeda affiliates and others linking them with IS.

According to a new study by two researchers, James Barnett and Umar Musa, given the fluidity and fractious nature of jihadi alliances in the Sahel, some of the original members of the group may have been affiliated with JNIM in 2017-2018, but “present evidence points to the majority of so-called Lakurawa activity, particularly in Sokoto and northern Kebbi states, as being the work of ISSP militants.”

This has added a fresh layer to the controversy that has dogged U.S. policy in Nigeria since Trump declared last month Nigeria a “Country of Particular Concern” for failing to protect Christians,” and threatened to order U.S. troops into the country “guns-a-blazing.” Trump’s outburst caused a diplomatic row with Nigeria’s government and increased tensions within the country’s 230 million population. Since then, Abuja and Washington had been engaged in frenetic diplomatic talks which has seen delegations from both countries exchange visits and at least two congressional hearings in Washington.

The Christmas day bombing is the first public confirmation that both countries are now working together. According to a statement by Nigeria’s Minister of Information on Friday, December 26, the airstrike was conducted following “explicit approval by the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria.” The statement added that the operation was carried out “with the full involvement of the Armed Forces of Nigeria and under the supervision of the Honorable Ministers of defense, as well as the Chief of defense Staff.”

The operation was also its first test of what is at the moment still a patchy relationship. The key issues of disagreement remain what they have been all along: the religious framing of the country’s conflict and Nigeria’s sensitivity towards its sovereignty even as it welcomes foreign military assistance. Several established groups that monitor the violence argue that Nigeria’s conflict is complex and that they have seen no evidence that Christians are being killed at a greater rate than Muslims.

Yet, the Trump administration’s characterization of the conflict has not changed. This remains a sore point for President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, who came to power two years ago on a Muslim-Muslim ticket and is struggling to administer a country whose vast population is roughly evenly divided between adherent of both religions.

The simmering dissension has surfaced quickly in the immediate aftermath of the airstrikes. While Trump continued to frame them as part of his mission to protect Nigerian Christians from radical Islamists while promising more, Nigeria has struck a more even tone, insisting that the action is targeted at “terrorist violence in any form whether directed at Christians, Muslims or other communities.”

The day after the airstrike, Nigeria’s foreign minister, Yusuff Tuggar, was asked during an interview what he thought about Trump’s social media post framing the military strike as a defense of Christians, he replied “We’re focusing more on what has been done.” He added that Nigeria’s government is not going to “pore over the forensic details of what was said.”

Notwithstanding the gray areas, the emerging security cooperation between Trump and Tinubu testifies to both countries’ desire to work together to end a security crisis that has implications for the entire region. But what the last 48 hours has demonstrated is that there are underlying challenges that both countries need to work on for cooperation to prosper.

This is more the case now as there are indications that more strikes are likely in the coming days or weeks. Brant Phillip, a security analyst who has been tracking flight patterns of U.S airplanes and UAVs over Nigeria’s sky in the past weeks, reported on X that following a one-day pause, the U.S has resumed Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) flight missions, this time on ISWAP enclaves in the Sambisa forest of Borno state in the northeast of Nigeria.

“Even when undertaken with consent or cooperation, foreign military action that appears misaligned with local realities risks strategic blowback,” Professor Adewale said. “It can undermine state sovereignty, fuel suspicion among local populations, and reinforce perceptions that external actors do not fully understand the societies they intervene in.”

- US arming Nigeria is becoming a crime against humanity ›

- What Trump should know before going 'guns-a-blazing' into Nigeria ›