The new British “National Security Strategy” is not really a strategy at all, but a mess of conflicting (and often fantastical) goals and unexamined assumptions.

For this, two things above all are responsible. The first is the unexamined tension between, on the one hand, the strategy’s promise of a “systematic approach to pursuing national interests,” and, on the other, the repeated assertion that these interests are totally and inextricably bound up with Britain’s alliances. For it should be clear by now that “allies” cannot necessarily be relied on, and that in certain circumstances the agendas of allies are not a security asset but rather a source of greatly increased danger to Britain.

The second fundamental problem, one that has plagued Britain for many years, is the tension between the professed commitments set out in the “Strategy” and the practical limits on Britain’s resources. The authors should have paid attention to the famous maxim of former French prime minister Pierre Mendes-France: “To govern is to choose.”

When, however, the choices involved are difficult and painful, to choose requires not just knowledge and intelligence but also moral courage. In this case, the authors do not understand or have chosen to ignore the meaning of the word “priority.” Having set one “priority” in NATO and the alleged Russian threat, they then add more and more “priorities.” The new “strategy” promises to bring ambitions and resources into alignment through a huge increase in military spending and military industry; but even if this happens — and there are good reasons to think that it is fiscally impossible — it will not be remotely enough to achieve all the conflicting goals set out in this document.

For almost 70 years, the British establishment has sought to maintain its posture as a great power on the shoulders of the United States. The result in the case of this “Strategy” is that it is suffused with U.S. language, U.S. assumptions, and U.S. (and Israeli) agendas. Thus, Western democracies are threatened by “authoritarian aggression,” the “rules-based order” is threatened by Russia, Chinese, Iranian and North Korean “revisionists,” and “European and Indo-Pacific security are inextricably linked.”

This document sets out a legitimate national interest argument for British defense co-operation with Australia in terms of a boost to British military shipbuilding, through the “Aukus” agreement under which the US, UK and Australia will co-operate to build a new generation of nuclear attack submarines to be delivered — hopefully — about 20 years from now. This project would create about 7,000 new jobs in the UK.

The problem is that, echoing the discourse of Washington, it wraps this in hostile language about China that goes far beyond any real Chinese threat to Australia or international trade, and impossibly far beyond any Chinese threat to Britain. It is not just that this adds a completely unnecessary element of tension to Anglo-Chinese relations; it also ignores the fact that, if there were a serious Chinese military threat to Australia, there would be almost nothing the British armed forces could do about it.

One aspect of the would-be British role in the “Indo-Pacific” is symbolized, literally, by the little image of a British aircraft carrier next to the priority of “developing relationships in new domains.” One of Britain’s two carriers, HMS Prince of Wales, has indeed just been sent on a temporary deployment to the Indian and Pacific Oceans as part of a British carrier “strike group.”

According to the British government, one objective of the mission is “to declare the Queen Elizabeth-class carriers with all their constituent parts fully operational.” But the British carriers are well known not to be “fully operational.” Both have suffered repeated technical problems. They are unable to carry their full complement of (U.S.) fighters. The Royal Navy claims that the Indo-Pacific task force is “international by design,” but in actual fact it is international by necessity, since Britain cannot provide enough escort vessels.

Oddest of all is the statement that this Pacific deployment is also intended to “reaffirm the UK’s commitment to NATO.” NATO stands for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, not the Indo-Pacific Treaty Organization. With one British carrier at sea, the other is effectively immobilized for lack of aircraft, escort vessels and spare parts. How then is the Royal Navy to play its promised leading part in deterring or fighting the Russian threat that the National Security Strategy repeatedly identifies as the greatest direct threat to Britain and Europe? One of the three escorting frigates is provided by Norway, which has only four frigates. What has become of the supposed Russian threat to Norway?

On the part of the Norwegians, this is simply a continuation of the old European trick of making purely symbolic contributions to U.S. operations elsewhere in the world to try to persuade Washington to remain committed to European security. If so, however, this is a mission on autopilot, for Undersecretary of Defense Elbridge Colby (echoing a widespread view in Washington) has reportedly told the British that they are not really needed in the Pacific and should concentrate on the defense of Europe.

But the British establishment simply cannot let go of the desire to play a role, any role, on the world stage. Thus on page 23 of the “Strategy” we read that,

“Sovereignty over the Overseas Territories must be protected against all challenges so that, for those who live in the Territories as British nationals, their right of self-determination is upheld…We will maintain our military presence in Gibraltar, the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri & Dhekelia, Ascension Island, the Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands to deliver UK defence objectives.”

We should all of course support the right of the British Nationals of South Georgia and the South Sandwiches to self-determination — if such people existed. Alas, the only residents are seabirds and penguins. Then again, it would be a great deal less dangerous for the Royal Navy to spend its time protecting the British penguins’ Sandwiches than poking China in the eye. As for Gibraltar and the bases on Cyprus, the only conceivable “challenges” to them are from Spain and Turkey — both fellow NATO members.

Even this “Strategy” cannot quite manage to turn Russia into a threat to the British Sandwiches; though not, one suspects, for want of trying. But if Antarctic penguins, 8,000 miles from Britain’s shores, are “British nationals,” then it is easier to swallow the strategy’s statement that Ukraine — a mere 1,000 miles away — is Britain’s “neighbor.”

The British government and its National Security Strategy seek to justify the huge increase in British military spending to the British public (at a time of economic stagnation and severe fiscal pressure) above all on the basis of an alleged direct, serious and imminent Russian threat to Britain itself. The inconsistency here should be obvious. If such a threat really exists, then - as in the years before the First World War - Britain should be reducing its commitments elsewhere in the world in order to concentrate them closer to home. Deployments to the Indo-Pacific and Ukraine should both be off the table. Instead, Britain is declaring a “100 year” pact with Ukraine, and proposing a leading and permanent British military presence as part of a European “reassurance force.”

And while the “Strategy” is permeated with veiled anxiety about the unreliability of America as an ally, the policies being adopted by the British establishment towards Russia and the Ukraine War make Britain more and more dependent on Washington. Should Britain actually send troops to Ukraine, that dependence would become absolute, for as Prime Minister Keir Starmer has himself stated, such a force would rely totally on U.S. backup and protection.

It seems deeply foolish for Britain to choose to rely more on an unreliable U.S. This reliance will make it more and more difficult for Britain to distance itself from U.S. agendas elsewhere, especially in the Middle East. The language of the British “Strategy” simply parrots the U.S. in repeatedly portraying Iran and unspecified terrorists as the threat to order in the region. The word “Israel” never appears. The document talks of the need for Britain to exploit its diplomatic links to Commonwealth countries – but the great majority of those countries would regard the picture of Middle Eastern security set out here as a gross and immoral falsification.

For as the events of recent months have made clear, it is Israeli actions and ambitions that pose the greatest threat to order and security in the Middle East, to British interests and British lives in the Gulf, and to social peace and political stability within Britain itself. But what can the “Strategy” — or any British government — do about this if the U.S. establishment is completely subservient to Israel and the British establishment is totally reliant on the U.S.?

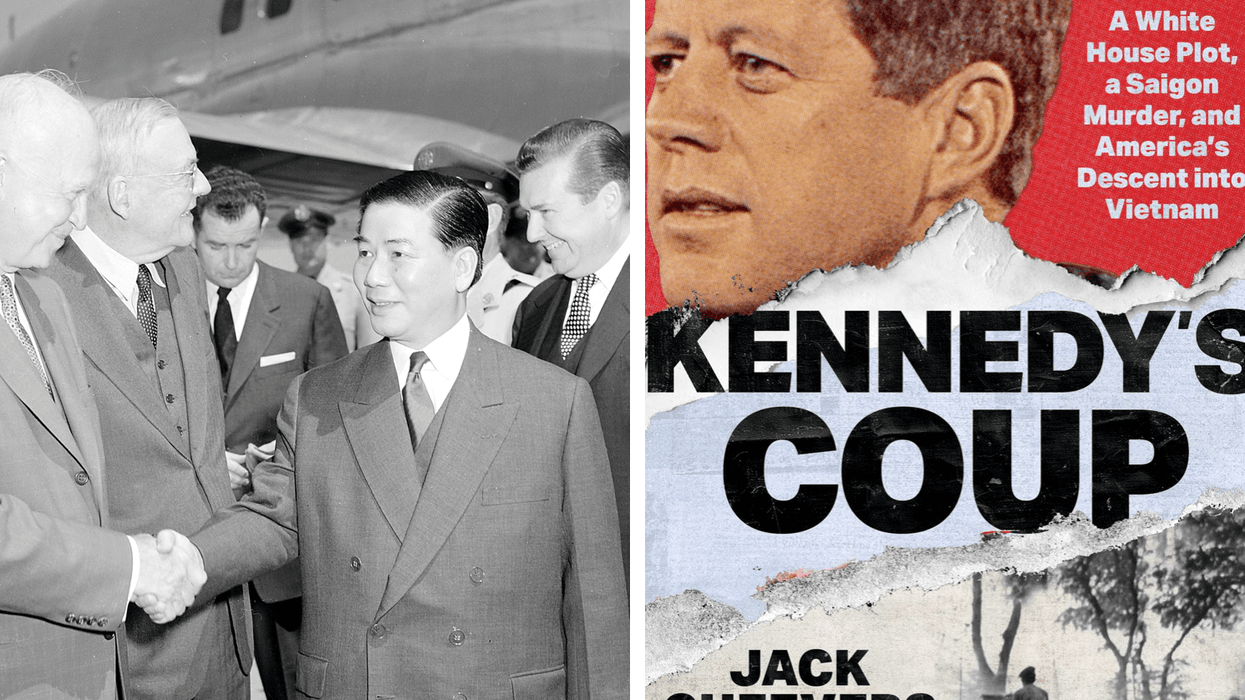

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)