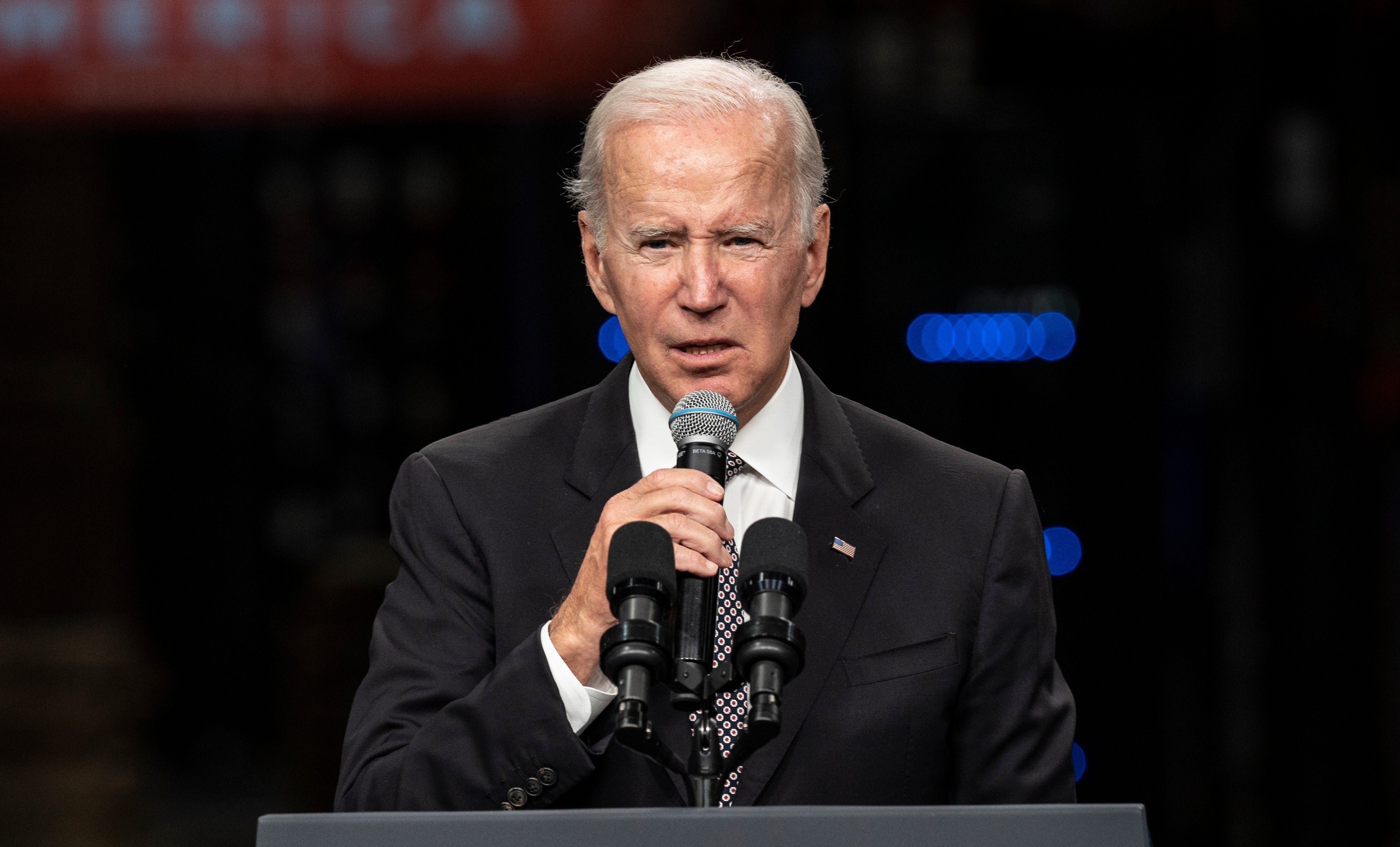

When Joe Biden was running for U.S. president, he promised to reverse many of his predecessor’s decisions on foreign policy, generally hewing towards more restraint and diplomacy, and less bluster, militarism, and unilateralism. That included restoring the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) from which Donald Trump withdrew in 2018 — despite evidence, shared even by his own officials, that the deal was delivering on its core objective to block Iran’s pathways to a nuclear weapon. On December 7, 2023, Biden’s nominee for deputy secretary of state, the current National Security Council Coordinator for Indo-Pacific Affairs, Kurt Campbell, effectively declared the JCPOA dead.

“I don’t think anyone sees that there’s any chance in the current environment to go back to the JCPOA. It’s not up for discussion,” Campbell told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee during his confirmation hearing. Pushed by Republicans who also expressed outrage over the “cash for hostages” deal (which conditionally grants Tehran access to its own $6 billion for strictly humanitarian use in exchange for a prisoner swap), Campbell also noted that the U.S. “must be sending a military message that provocations will be met, and met with stern responses. We must isolate them diplomatically, internationally.”

Although the prospects for a revived JCPOA have been dim since at least 2022 — for which Iran carries a fair share of blame — officials from the Biden administration until now have largely refrained from using such threatening language against Iran. Conclusively abandoning any effort to revive the JCPOA does not serve U.S. interests and is in fact counterproductive.

Addressing students at Tehran University a few days after Campbell’s Senate testimony, Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir Abdollahian downplayed the relevance of the JCPOA by reportedly saying that the “more we move forward, the more JCPOA becomes pointless. We will not force ourselves to remain in the narrow tunnel of the JCPOA forever.”

So, the Biden administration finds itself in the rather awkward position of effectively agreeing with Tehran, but this was a self-inflicted problem: by refusing, for three years now, to engage with its critics and the broader public on the agreement’s benefits to the U.S. and global security, it has allowed the notion that the JCPOA was some kind of reward for Iran, rather than a deal that strictly curbed Tehran’s nuclear ambitions, to become conventional wisdom. As is evident in Abdollahian’s remarks, Iranians today certainly do see the JCPOA as a “narrow tunnel” that limits their options.

Indeed, Abdollahian’s references to “mov[ing] forward” are about advances in Iran’s nuclear program. In mid-November, the International Atomic Energy Agency, the U.N. nuclear watchdog, voiced alarm that Iran had amassed enough uranium enriched up to 60 percent purity for three atomic bombs, even as Tehran continued to bar several IAEA inspectors from carrying out their tasks, a step the agency deplored as “extreme and unjustified.” As a result of Iranian actions following the U.S. exit from the deal, the IAEA currently estimates that Tehran’s stockpile of enriched uranium is 22 times greater than it would have been if the JCPOA had remained in effect. Clearly, Iran is now far closer to being able to produce an actual bomb in a very short time if it decided to do so.

If ever there was a mechanism that would prove effective in preventing Iran from acquiring a bomb, it was the JCPOA. In light of Abdollahian’s remarks (which clearly reflect a growing skepticism about the JCPOA in Iran), the Biden administration, by publicly disowning the deal, is in fact removing obstacles to further Iranian nuclear escalation.

Unless Biden is prepared to accept the advice of the late international relations scholar Kenneth Waltz, who, in an influential 2012 Foreign Affairs article, argued that an Iranian bomb would stabilize the Middle East, it is not clear what his administration would do in place of a revived JCPOA to check additional Iranian nuclear advances.

Campbell emphasized the “current environment” as an additional factor rendering a JCPOA revival infeasible. In fact, if he was referring to the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza, then it is precisely such a conflict that makes some sort of a direct dialogue between Washington and Tehran — on nuclear, but also regional security issues — all the more urgent if a wider war is to be avoided. Substituting such a dialogue with military threats at a moment when the U.S. is providing Israel virtually unconditional support, including the lavish replenishment of its arms stocks, the deployment of marines and two aircraft carrier task forces to the region, and the veto of a U.N. Security Council Resolution calling for a ceasefire, could do more to incentivize Iranians to seek a nuclear deterrent than anything else.

Vows to isolate Iran “internationally and diplomatically” are also unwarranted as Iran, despite its rhetorical support for Hamas, has so far demonstrated considerable restraint. While hardline ideological hostility to Israel is wired into the Islamic Republic’s identity, the actual position Tehran adopted towards the Israel-Palestine conflict is much more nuanced, more in line with the Arab and Islamic (and indeed broad international) mainstream consensus that insists on a viable two-state solution. Instead of building on these shifts, however modest and tentative, Washington seems to prefer to double down on confrontation.

The sad irony is that this explosive situation could have been avoided had Joe Biden had the courage and wisdom to deliver on his own election campaign promise to restore the nuclear agreement with Iran. It would not have solved all the problems between Washington and Tehran, but a working agreement would have removed one major source of instability in the Middle East. By building on it, both countries may have even been brought to engaging on regional discussions which would have not only further normalized their relationship, but also contributed to the prevention of a wider war in the Middle East.

- Revealed: Biden rejected way forward in Iran deal talks ›

- Biden's Iran policy has been a total failure ›

- Biden's 'no Iran deal, no crisis' policy is unsustainable ›

- Killing the Iran nuclear deal was one of Trump's biggest failures | Responsible Statecraft ›

- How Biden dropped the ball on the Iran nuclear deal | Responsible Statecraft ›