A senior Democratic lawmaker on Wednesday said it was ‘a problem’ that many in his party have been trying to out-hawk Republicans on foreign policy and that Democrats need to be more aggressive in advocating for diplomacy approaches abroad, particularly with respect to China.

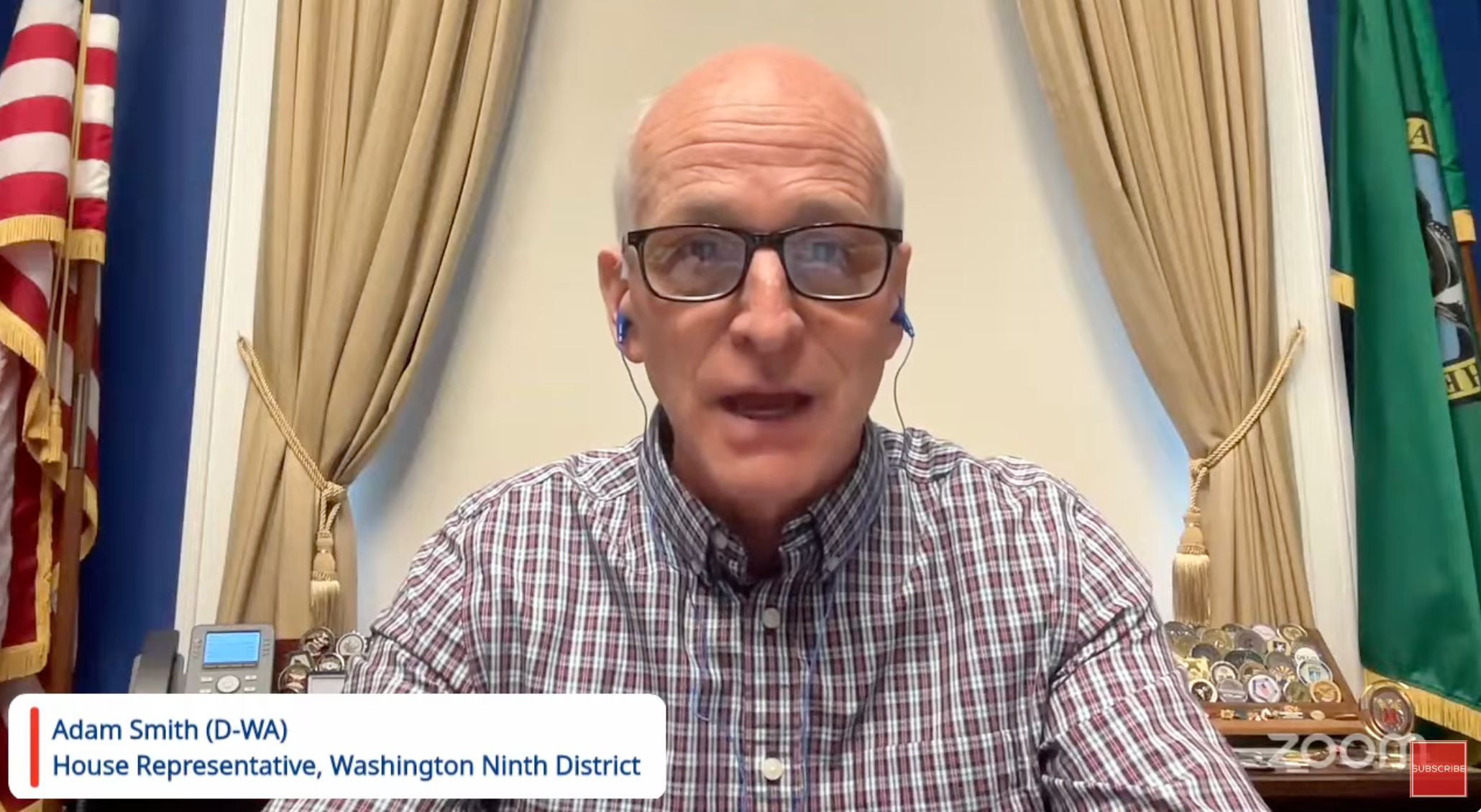

During a discussion hosted by the Quincy Institute — RS’s publisher — with House Armed Services Committee Ranking Member Rep. Adam Smith (D-Wash), QI executive vice president Trita Parsi wondered why — pointing to Vice President Kamala Harris campaigning for president with Liz Cheney and Sen. Elissa Slotkin’s (D-Mich.) recent embrace of Ronald Reagan’s foreign policy — the Democratic Party has shifted away from promoting diplomacy, opposing “stupid wars,” and celebrating multilateralism.

“There is no question that that is a problem,” Smith said, adding that he thinks Democrats often fear being criticized for promoting talking with adversaries as being weak and then feel they don’t get enough support from the left. “One of the beefs I have with the left side of the spectrum is they’re always banging on us for not doing one thing or another. … We do four things and it’s the fifth thing we didn’t do.”

Smith said that Democrats need to “much more aggressively embrace diplomacy” and that part of that should be a refocus on how the United States deals with China.

“Everyone wants to talk about what their plan is to beat China. Anytime anyone says that, you got to ask the question, ‘what is your plan to peacefully co-exist with China?’” he said. “We are completely ignoring even trying to figure out how to make that work and constantly focused on how to beat them.”

Smith acknowledged that China “does have expansionist ambitions” and that the U.S. has “to be able to have an adequate deterrence” to push back and that “we need to be able to compete economically.” But, he said, the U.S. needs to work with China on a whole host of shared interests, like global warming, health issues and energy needs.

“What’s your plan to get along with China?” he asked.