Iran doesn’t have nuclear weapons. North Korea and Israel do. But English-language media cares more about Iran’s non-existent atom bomb than North Korea’s real nuclear missiles, data suggests, while Israel’s arsenal barely gets a mention.

All three countries have been in the headlines lately. After the discovery of 84 percent enriched uranium in Iran — nearly weapons-grade — CIA director Bill Burns said that Iran has not yet decided to build a nuclear bomb. Even so, the Biden administration encouraged Israel to “do whatever they need to” towards Iran to prevent it from building a nuke.

Meanwhile, U.S. officials have been holding drills for a North Korean nuclear attack, after months of escalation between South Korea and North Korea.

Politics play a huge role in driving news coverage of different issues. At best, the press seeks to help the public make informed democratic decisions, so journalists cover issues related to their government’s policy. At worst, journalists allow the concerns and taboos of the elite to determine what issues deserve attention and how they should be covered.

English-language coverage of different countries’ nuclear programs certainly reflects American political concerns. Although North Korea is an adversarial state with the power to strike inside America, the U.S.-North Korean conflict is mostly frozen in place. Washington has a lot more room to keep the U.S.-Iranian conflict active, or even escalate it.

Politicians often cite Iranian threats against Israel as a reason to fear Iran’s nuclear capabilities. But as the late U.S. secretary of state Colin Powell privately argued in 2015, the “Iranians can’t use [a nuclear weapon] if they finally make one. The boys in Tehran know Israel has 200, all targeted on Tehran, and we have thousands.”

The American people do not necessarily understand what “the boys in Tehran” do. In 2010, a poll found that 70 percent of Americans believed Iran already had nukes. In 2021, 60 percent still believed in the existence of Iranian nukes, with another 23 percent of Americans claiming that they did not know. Only about half of respondents on the 2021 poll even knew that Israel had nuclear weapons.

“In other words, more than four-fifths of the public doesn’t know the correct answer to a simple question about a matter of fact on one of the most high-profile foreign policy issues of the last 15 years,” foreign policy commentator Daniel Larison wrote in 2021. “That is what decades of misinformation and propaganda will get you.”

Media coverage regularly refers to Iran’s “pursuit of nuclear weapons,” despite the fact that neither the United States nor Iran are claiming that there is an active Iranian nuclear weapons program. While it is rare for journalists to outright claim that Iran already has a nuclear weapon, there is a lot of vague or inaccurate coverage about Iranian nuclear activities that could leave readers with the impression that Iran is pursuing or even has nuclear weapons.

“Hawks make a constant effort to promote falsehoods about foreign threats in order to frighten the public into acquiescing to more aggressive policies, and eventually they use those falsehoods to agitate for military action,” Larison added.

Over the past 12 years, English-language media has mentioned the word “Iran” or “Iranian” alongside the word “nuclear” or “atomic” an average of 1.46 times per million words of newsprint. North Korea was mentioned in the same context 0.247 times per million words.

Israel was only mentioned alongside “nuclear” 197 times in total, a minuscule 0.0117 mentions per million words.

Even a more narrow search for phrases related to nuclear weapons shows that Iran — despite the country not possessing nuclear bombs — was mentioned more than North Korea, except during a few crisis periods. Again, Israel’s nuclear weapons were barely mentioned.

These results came from searching the News on the Web (NOW) Corpus, a database of journalistic writing from 20 different countries updated daily. The NOW Corpus allows synonym searches, so running a search on “North Korea* =nuclear =weapons” also returns phrases like “North Korea’s atomic weapons” and “North Korean nuclear arms.”

Since the discovery of uranium enrichment facilities in Iran in the early 2000s, the Iranian nuclear program has been a central concern of U.S. politics. Although the CIA believes that Iran gave up trying to build a nuclear bomb in 2003, the Iranian government has continued to enrich uranium, and U.S. presidents have threatened to attack Iran to prevent the country from even approaching nuclear weapons capabilities.

Iran agreed to limit its nuclear activities in 2015 in exchange for lifting international economic embargoes on the country. The Trump administration tore up the deal, believing that more pressure could either gain new concessions or collapse the Iranian government outright, neither of which occurred.

The Biden administration has so far failed to de-escalate the situation. Although President Joe Biden originally promised to rejoin the 2015 agreement, the ongoing uprising in Iran and Iranian weapons sales to Russia have killed Washington’s appetite for diplomacy.

The United States has been down this road with another rival. In the early 1990s, North Korea had agreed to restrict its nuclear enrichment in exchange for international energy aid. However, both Washington and Pyongyang accused each other of violating the terms of the agreement, and the Bush administration pulled out of the deal in 2002.

Absent restrictions on its program that were part of the agreement, North Korea tested its first nuclear warhead four years later.

Because North Korea is still officially at war with U.S. ally South Korea, the existence of a North Korean bomb has led to some frightening close calls. Former president Donald Trump threatened North Korea with “fire and fury” in response to North Korean missile tests in 2017, kicking off months of tension that ended with a series of U.S.-North Korean diplomatic meetings.

In spite of the heightened danger — or perhaps because of it — the North Korean threat does not seem to get a lot of ongoing attention. The United States has to tread carefully, and drawing attention to North Korea in any way does not seem to bring much political benefit. Despite polls showing that the American public wants diplomacy in theory, U.S. leaders have taken political punishment for trying.

“North Korea has become a sort of ‘out of sight, out of mind’ issue for many Americans,” professor Benjamin Engel said in response to 2022 poll results showing declining public interest in the Korean conflict.

American politicians have more to gain and less to lose from publicly raising tensions with Iran. While polls show that Americans prefer diplomacy when dealing with Iran, “a big chunk of the population is already willing to support the use of force,” as pollster Dina Smeltz noted in 2019.

Ironically, the less-intense Iranian threat makes escalation easier to stomach. However catastrophic a war would be for the region, and whatever its cost may be for the U.S. military, Iran does not yet have the same ability to retaliate against American cities that North Korea does.

Israel has also had an undeclared nuclear arsenal since 1967, with anywhere between several dozen and several hundred warheads. There are also South African claims that Israel helped the Apartheid-era government develop its own nuclear weapons, a charge that Israeli leaders have denied.

English-language media would be expected to pay less attention to the Israeli arsenal. Israel is a U.S. partner and Americans have no reason to fear an Israeli attack. As for the South African issue, the country dismantled its nuclear arsenal in 1993, making any Israeli involvement more of a historical curiosity than a live issue.

However, the near-total silence is on purpose. After the Nixon administration discovered the Israeli nuclear program, it pressured Israel not to make any “visible introduction of nuclear weapons.” Publicly testing a bomb could provoke an international reaction and run afoul of American arms control laws.

U.S. officials have kept up the charade, treating the existence of an Israeli bomb as a state secret. The journalist Sam Husseini has documented years and years of American politicians avoiding questions about the topic, sometimes in absurd ways.

While they have kept their own nuclear option quiet, Israeli politicians have spent the last three decades raising the alarm about Iranian nuclear developments.

In the mid-1990s, the Labor Party of Israel made a “sudden” and “intense” shift towards portraying Iran as the greatest threat, with a particular focus on the budding Iranian nuclear program, wrote Quincy Institute vice president Trita Parsi in his 2007 book, “Treacherous Alliance: The Secret Dealings of Israel, Iran, and the United States.”

The Israeli military brass was skeptical, and tended to see belligerent Iranian rhetoric as more bark than bite. According to Parsi, hyping up the Iranian menace was part of a strategy to pitch the Labor Party’s “New Middle East” vision to skeptical Israeli voters, potential Arab partners, and the United States.

The late Labor Party leader Yitzhak Rabin “played the Iranian threat more than it was deserved in order to sell the peace process,” Israeli professor Ephraim Inbar told Parsi.

“We needed some new glue for the [U.S.-Israeli] alliance,” Inbar continued. “And the new glue…was radical Islam. And Iran was radical Islam.”

Three decades on, the Labor Party is out of power, but parts of its vision are alive and well: an Israeli-Arab alliance, underwritten by U.S. military support, with Iran as the unifying enemy.

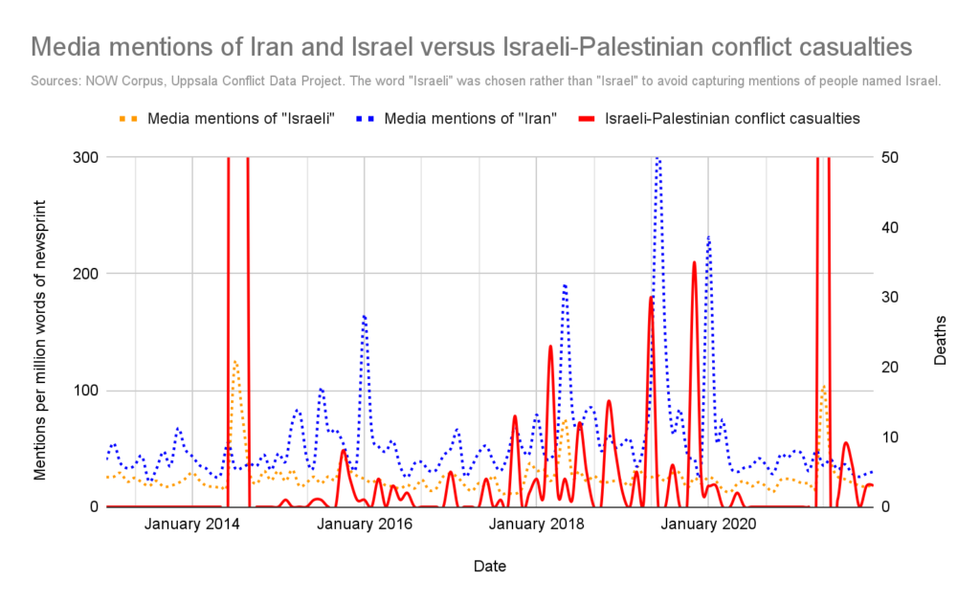

During the Trump era, several spikes in Israeli-Palestinian violence were followed by U.S.-Iranian escalations. The decision to pull out of the nuclear deal, to nearly bomb Iranian air defenses in July 2019, and to assassinate Iran’s General Qassem Soleimani all came within a month or two after clashes in Gaza. These patterns are reflected in the media coverage data.

It’s a common claim that the “Western media” is ignoring or over-sensationalizing a certain issue. Such complaints are hard to judge, because there is no universal scale for how much attention a particular story deserves.

The parallels between the Iranian, North Korean, and Israeli nuclear issues allow for a side-by-side comparison over time. All three countries’ nuclear programs are central to U.S. foreign policy, yet the patterns of coverage over time and overall amount of coverage are quite different.

It seems that the existence of a rogue nuclear program or the danger to American cities is not enough to grab headlines — only the possibility of going to war over it is.