NEW DELHI, INDIA —New Delhi in early March is a pleasant city with daytime temperatures in the comfortable 80s and a nip in the air in the evenings. But it was less than comfortable in the conference rooms and salons of the G20 foreign ministers’ meeting on Thursday.

A staid group historically focused on matters of global economic governance, the G20 has been roiled since the Ukraine war by a sharp split between the United States and its allies on one hand and Russia and China on the other. The last G20 leaders’ summit in Bali in 2022 produced a joint statement at the last minute after a skillful effort led by chair Indonesia. This year’s chair, India, has been less than successful in forging such a compromise. Russia and China reportedly refused to sign on to a repeat of the Bali statement, which left New Delhi scrambling.

India, like other Global South states, would greatly prefer the Ukraine war to simply go away. As its prime minister said, it was interfering in work to tackle a host of global problems, from debt relief to climate change. During its G20 presidency this year, New Delhi aims to prioritize these issues as it centers the Global South’s concerns in the forum.

It would be tempting to interpret the deadlock as a failure of the G20 itself, and there’s a good case to be made that the grouping is in trouble. But the argument can be taken too far. As has been reported, Blinken and Lavrov had a 10-minute meeting on the New Delhi meeting’s sidelines. The conversation is unlikely to lead to any immediate breakthrough in Ukraine. But the fact that the two foreign ministers felt the need to speak at all to each other when all bilateral conversations of a strategic nature have practically ceased speaks to the utility of forums like the G20.

The final denouement of World War II with allied tanks entering Berlin and Japan surrendering, so deeply etched in America’s view of history, is not the best history lesson. The fact is that most wars end in some sort of political settlement rather than a complete victory of one side over the other.

The moralist rhetoric from Washington, matched by the hard nationalist one from Moscow, may appear to rule out the possibility of a deal in Ukraine. But great powers are also aware, if dimly, of the political risks of endless war. This may explain the Blinken-Lavrov conversation. Otherwise, adversaries that have nothing to say to each other would not see the need to speak.

Less reported, but also significant, was a conversation between the Indian and Chinese foreign ministers during the New Delhi meet. The two Asian giants have been locked in a tense, armed standoff since 2020. Last month’s Munich Security Conference also provided a convenient location for Blinken and his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi to converse after a canceled visit to Beijing by the U.S. Secretary of State in the wake of the spy balloon brouhaha. If multilateral groupings did not exist, we would have to invent them.

The G20 will therefore continue to stagger along. It is unlikely to solve the serious and urgent problems of debt relief, pandemics, climate change, and food security this year — far more pressing challenges for most denizens of this planet than a war in one corner of the Eurasian landmass. But by simply existing and meeting, possibilities are kept alive for great powers to grudgingly acknowledge what they already know — that though some may eagerly seek “extreme competition” and others refuse to budge from irredentist desires, staking claim as global or regional leader means that you must show at least some interest in the art of the deal.

This is perhaps where a sliver of hope still remains for an existentially challenged world.

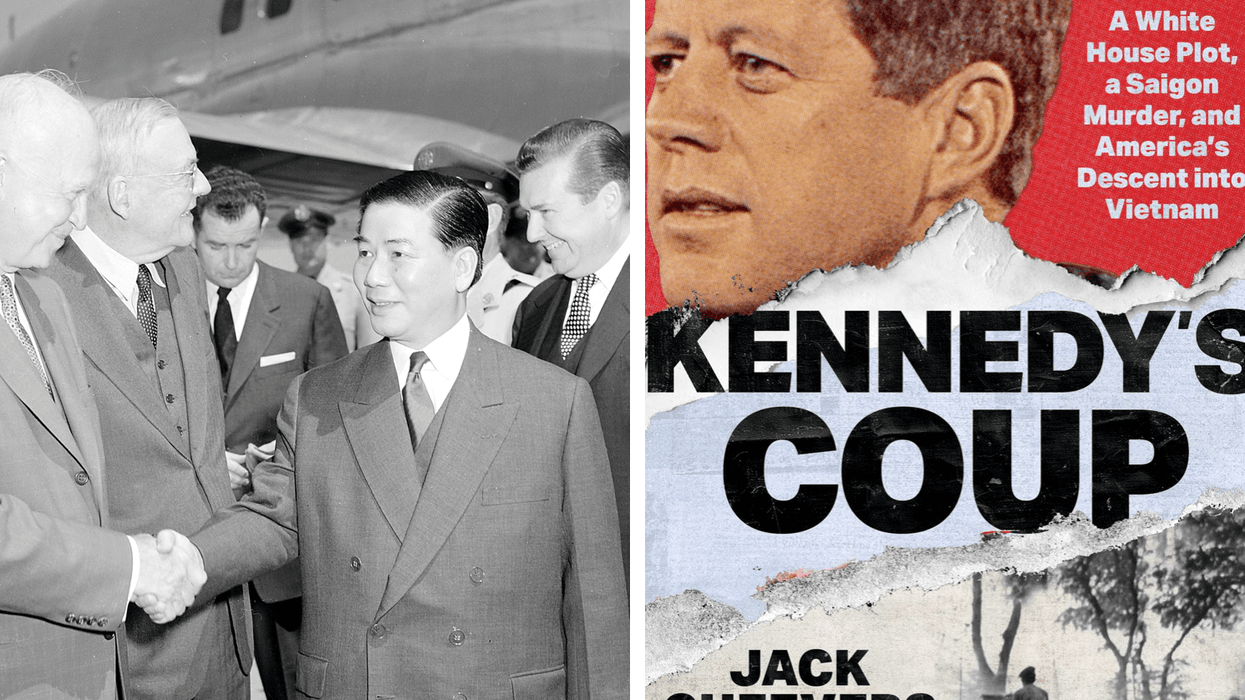

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)