One day after the New York Times published newly released video footage of a U.S. drone strike that killed 10 innocent civilians in Kabul, Afghanistan last year, a group of 50 U.S. senators and House members wrote to President Biden calling on him to “overhall U.S. counterterrorism policy” with a greater emphasis on human rights and international law.

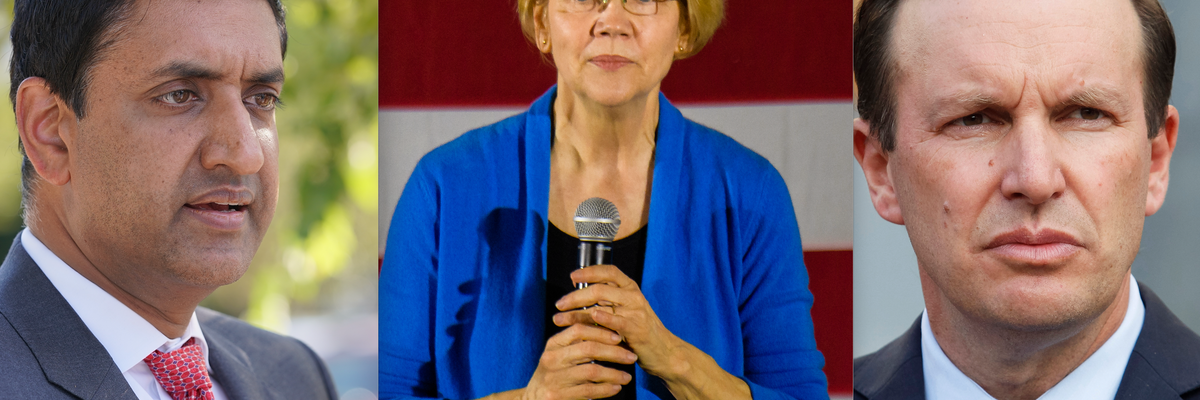

The letter — led by Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Chris Murphy (D-Conn.), as well as Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) — urges Biden to “prioritize non-lethal tools to address conflict and fragility, and only use force when it is lawful and as a last resort.”

The lawmakers note that U.S. airstrikes since 9/11 have killed at least 48,000 civilians with drone strikes alone accounting for 2,200, including 450 children. “Alarmingly,” they write, “the actual numbers are likely significantly higher given the difficulty of comprehensive reporting and the United States’ consistent underreporting of these numbers and reported refusal to investigate reports absent ‘potential for high media attention.’”

The letter is admirable and a step in the right direction but there is more these lawmakers themselves can do. For example, Human Rights Watch’s Sarah Yager and Leah Hebron have argued on these pages that given the lack of accountability for U.S.-caused civilian casualties, Congress can launch investigations similar to the 2008 inquiry on detainee treatment.

“The critical piece,” they said, “is to evaluate not just the individual strikes but systemic failures by the U.S. military and its civilian leadership — failures to set the right guidance on civilian harm, to follow up on investigations, to avoid safeguards and oversight.”

Congress could also repeal the laws that the executive branch has used to justify these airstrikes that cause civilian casualties — the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Force against the perpetrators of 9/11 and the 2002 AUMF greenlighting the invasion of Iraq. They do nothing but prolong America’s forever wars, which President Biden himself has pledged to end.