Across Eurasia and the Middle East, fixation on the West or any other great power no longer carries the utility it once did.

From Turkey and Saudi Arabia, to Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, these countries are all playing a similar game – diversifying their foreign policy portfolios — what is fashionably called “multi-vector” foreign policy. The United States and its allies should support this trend rather than resisting it as it will guarantee that these countries avoid becoming reliant on an actor hostile to the collective West.

Explanations for this trend differ, but they mostly hinge on global developments. The definitive end of the U.S. “unipolar moment” and with it the ongoing traumatic unraveling of the entire post-Cold War order is often cited as the main catalyst. The U.S. is no longer seen as the only truly global and most responsible power, which, since the early 2000s, has inflicted serious damage on its own position with its disastrous invasion and occupation of Iraq, its ill-conceived policies of regime change in Libya and Syria, and its staunch support for Israel — all to the detriment of its prestige across the Middle East and beyond.

Related to the end of the American age is the relative rise of powers, notably China, Russia, and India, which increasingly present themselves as alternative geopolitical power centers. As the balance of power in Eurasia has grown less favorable to the collective West, so-called middle powers have found fertile ground to pursue a relatively independent foreign policy with the goal of diversifying their foreign policy portfolios.

Multi-vector foreign policy consists essentially of avoiding geopolitical dependence on any one major power in order to maneuver between several powers to one’s own advantage. It requires both diplomatic skill and economic and political heft.

Take, for example, the United Arab Emirates, which has avoided ditching the U.S., on which it depended for its security over decades, altogether and instead is opportunistically using the “China card” to extract greater military and economic benefits in its relationship with Washington. In some areas Abu Dhabi relies on Beijing, in others it favors Washington, while building closer economic ties with Moscow.

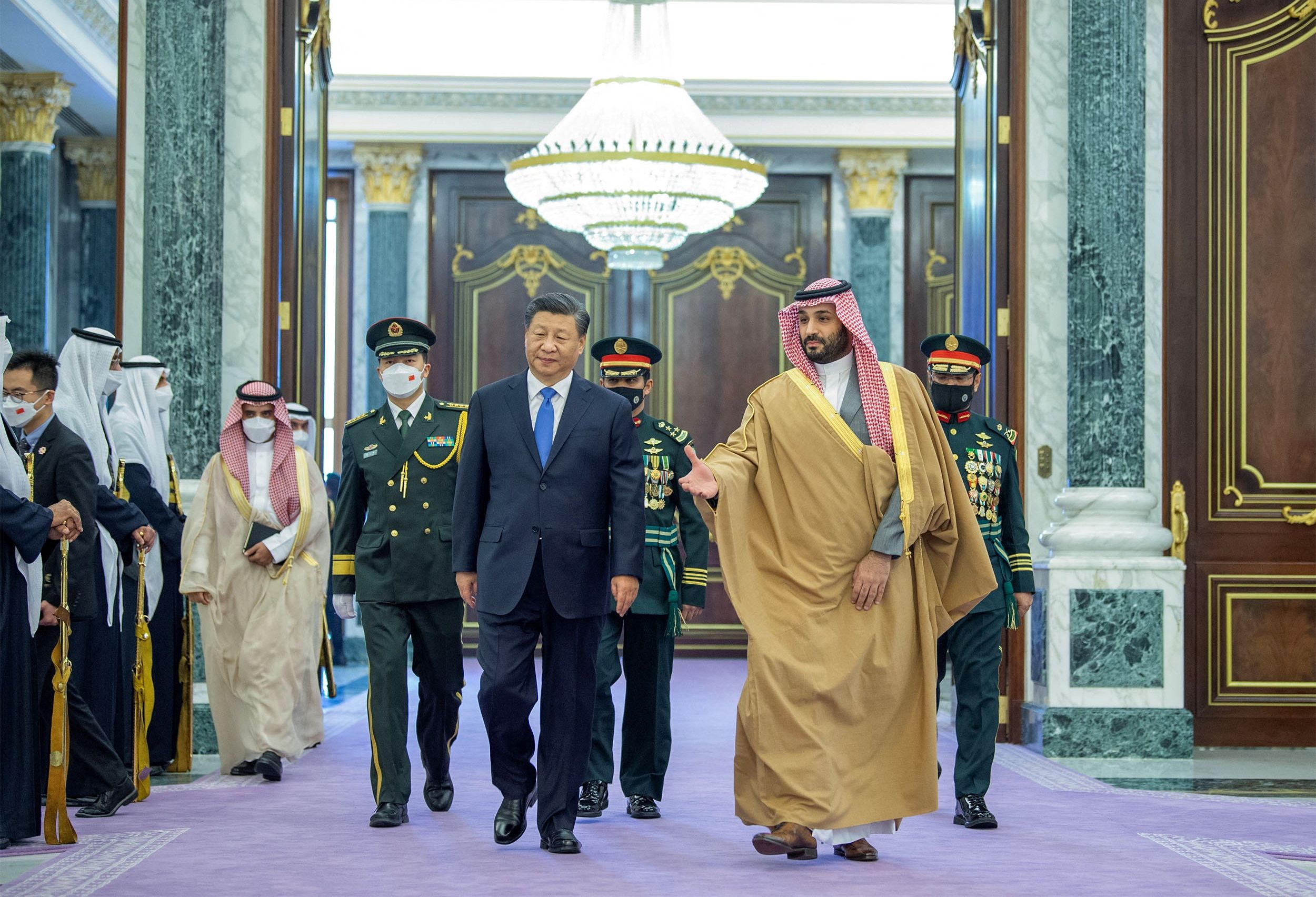

The pattern is similar to what Saudi Arabia has been doing over the past few years. In one case it pursues close economic and even security ties with China, achieves, with Beijing’s help, a rapprochement with Iran, but also attempts to seal a major security deal with the U.S. in exchange for normalizing ties with Israel, which in itself is conditional on the latter making irrevocable steps toward the creation of a Palestinian state.

In short, Riyadh is not giving up its traditionally close relations with Washington or replacing the U.S. with Russia or China. Instead, the kingdom, while still mostly reliant on Washington for its security, favors a multi-vector foreign policy that has thus far worked to enhance its growing prestige and importance in the international arena.

Diversification of foreign policy is not only peculiar to those countries that have historically leaned on the U.S. In Central Asia, Kazakhstan has been successfully navigating between Russia and China since the Soviet collapse more than 30 years ago. In this case, the U.S. has played a positive role as an additional balancing actor for Astana. The latter has tried to avoid over-dependence on Russia and has been skillfully using Moscow’s preoccupation with its war in Ukraine to limit its former imperial master’s projection of power.

Yet a multi-vector foreign policy would warn against Kazakhstan cutting links or otherwise alienating Russia altogether, even if it could do so, given its great oil and mineral wealth. China’s power and interest in Astana’s resources provoke some fear in Astana. Thus, the Russian factor is seen as a positive instrument to avoid economic dependence on China.

But multi-vector policy is by no means confined to the larger and more resource-rich countries of the Middle East and Central Asia. Much smaller states are also engaged in the game, as indicated by Azerbaijan and Georgia.

Baku has oil and gas which makes it important enough to use its relations with Russia, Iran, Turkey and the collective West to its advantage. More recently, Azerbaijan expanded ties with China, applied for BRICS+ membership, and elevated its status within the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. It aims to look eastward as well as westward while cultivating warm ties with Russia and cementing normal relations with the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Georgia is yet another example. Traditionally regarded as staunchly pro-Western and radically anti-Russian due to Moscow’s ongoing occupation of 20 percent of its territory, Tbilisi has embarked on a multi-vector policy. Ties with the West, though in distress due to the government’s recently approved foreign agent law targeting Western-funded NGOs, remain strong. But Georgia has expanded ties with China, Turkey and there seems to be some level of normalization with Russia.

Those are just a few examples. Turkey is pursuing much the same path, as are Uzbekistan and even Armenia despite its heavy reliance on Russia. Multi-vector foreign policy means dealing with a multiplicity of actors. This usually creates a highly congested geopolitical space, but it is what Central Asian, South Caucasian and Middle Eastern countries want.

Maneuvering being between China and the U.S. or the U.S. and Russia is far more dangerous than navigating among multiple actors when none of the major powers has enough clout to achieve its major diplomatic goals. Yet what the Middle East’s recent history has shown is that a single power striving to dominate the region has often led to poor foreign policy choices and resistance from local players.

Washington’s dominating position in the 1990s and early 2000s serves as a good example of how a single power was unable to stabilize or bring peace to the Middle East. Although no guarantee of ultimate success in stabilizing the region, a multiplicity of actors could be more advantageous in that regard. Enhanced influence exerted by China, Russia, and India, along with the persistence of Western leverage, could create a new and possibly more sustainable balance of power in the region.

Of course, multiple actors could also bring with them their own rivalries that may compound existing regional conflicts. But they could also create better conditions for diplomatic engagement between the great powers and thus facilitate an easing of regional tensions. The rise of multi-vector foreign policy fits into the world’s growing multipolarity and the shift toward more transactional approaches to international relations.

For the West, these developments should serve as a warning sign of the shifting balance of power. But, from a longer-term perspective, the U.S. and its Western allies should see multi-vectorism as a benefit insofar as it will work to prevent other great powers from dominating or imposing exclusive influence on any sub-region or single important state in Eurasia. This will allow the U.S. to present itself as an attractive actor whose help and power will be sought by others to help them avoid dependence on other big players and diversify their foreign policy.

- When will we accept the reality of a new multipolar world? ›

- For Russia-China, multipolarity is all about (usurping) the Benjamins ›

- Macron’s dissent: This is what multipolarity looks like ›

- Trump shouldn't overestimate US influence on the world stage | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Central Asia: The blind spot Trump can't afford to ignore | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Central Asia becomes middle power contender in new Trump era ›