UPDATE 8/13 12:45 P.M.: South Sudan denied it has discussed taking in Palestinians from Gaza with Israel.

The Associated Press is reporting that Israel is in talks with South Sudan to send Palestinians there, as Israel’s war on the Gaza Strip, and talk of it annexing the Gaza Strip, continues.

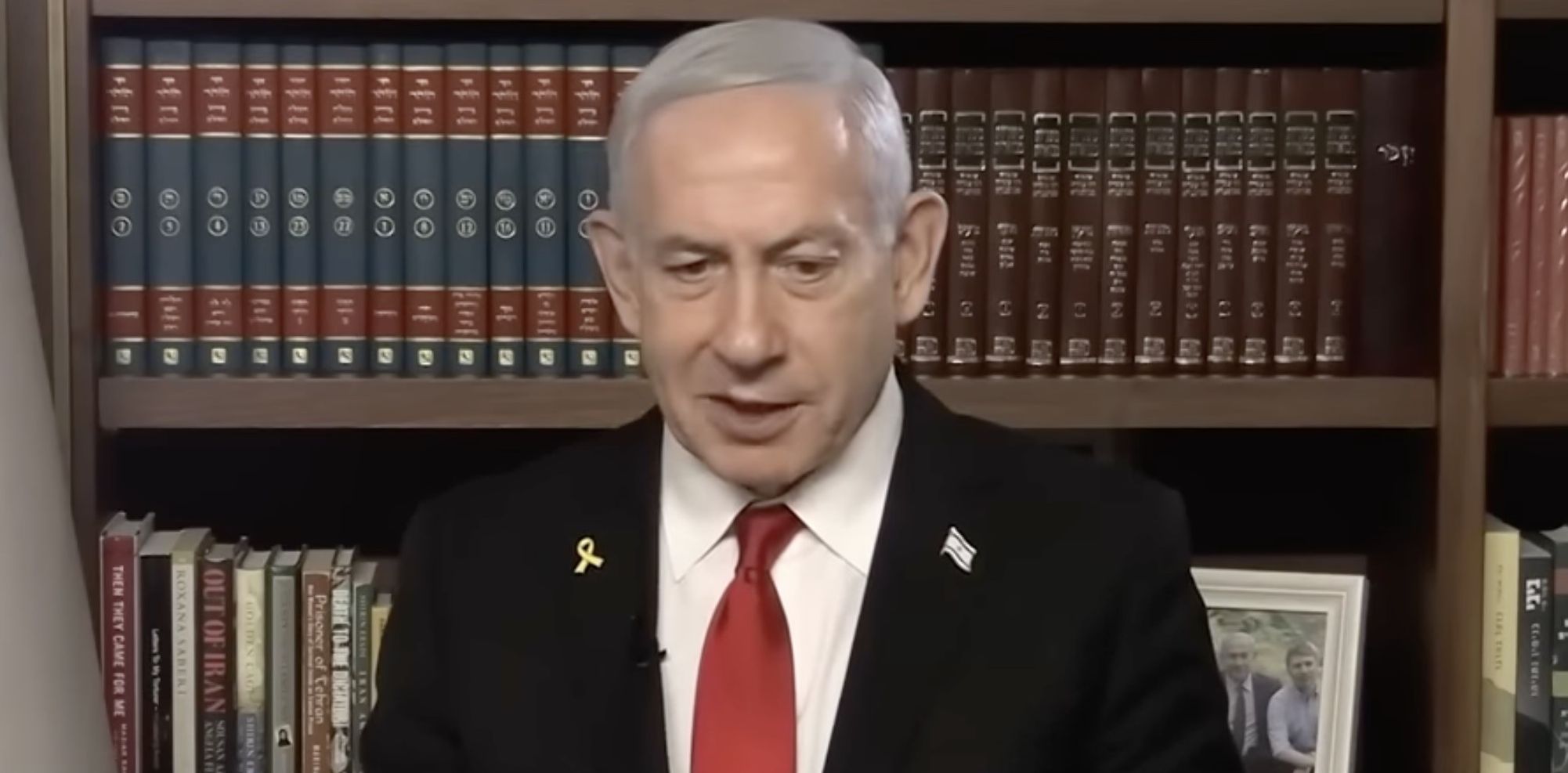

In an interview with Israeli outlet i24 today, Israel's Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu simultaneously expressed a desire to “allow” Palestinians to leave Gaza but said that, in turn, other countries would have to decide to “open their doors” to them. He did not mention talks with South Sudan during that interview, but said Israel was “talking to several countries” to receive Palestinians.

“Why does Gaza have to be a closed place?...Give them the opportunity to leave! First of all, to leave combat zones. Also to leave the strip if they want, we will allow that…We are not pushing them out either, but we are allowing them to leave,” Netanyahu said.

Netanyahu said that Palestinians would “leave combat zones” by exiting Gaza.

South Sudan sounds like an unlikely place for Palestinian to escape to. The country is experiencing its own food and aid shortages and is recovering from an extended civil war that took place after its independence from Sudan.

To that end, a leader of a South Sudanese civil society group told AP that Palestinians coming to South Sudan could find themselves in renewed danger, due to hostilities caused by “historical issues with Muslims and Arabs” in the region.

“South Sudan should not become a dumping ground for people,” the leader told AP.

Netanyahu’s attempts to relocate Gazans echo Trump administration talks back in March with other conflict-struck African countries, including Sudan and Somalia, to take in Palestinians as a means to carry out his plan to turn Gaza to a “Riviera of the Middle East.” For that plan to be successful, Trump officials have said Gazans would need to leave the Gaza Strip, either temporarily or permanently.