If Ukraine is to be secure and stable, America’s polarized Left and Right will have to find some common ground on ending the war.

The issue is after all not just of the utmost importance for Ukraine — it is critical for the security of the American people and the broader Western world. In the very worst case, it could lead to nuclear annihilation.

But even at lower levels of escalation, Russia has the ability to stoke existing tensions in the Middle East to a point where that region falls into general war, with the U.S. hopelessly entangled. And the longer the war continues, the more Russia will be incentivized to deepen its security cooperation with China, to America’s strategic detriment.

In principle, such a bipartisan consensus should not be impossible to achieve. Two key objectives are accepted by the great majority of the US establishment, backed by the great majority of the American people: We do not want a direct war between the US and Russia, leading to the strong risk of a catastrophic nuclear exchange; and we do want to preserve as much of Ukraine as possible as a viable independent state, with the chance of reconstructing its economy and eventually joining the European Union. A Ukraine that cannot rebuild itself will become an open wound in Europe, with dire implications for the region’s security and prosperity.

Unfortunately, at present, the US political debate on this issue includes very little discussion of how to achieve these two goals, while featuring an abundance of name calling. One side shouts “appeasers” and “Russian apologists,” while the other retorts with (mutually contradictory) accusations of “warmongering” and “weakness.”

Such excessive rhetoric has become the norm in American political campaigns, but if recent elections are any indication, there is a strong likelihood that it will continue after November, with disastrous consequences.

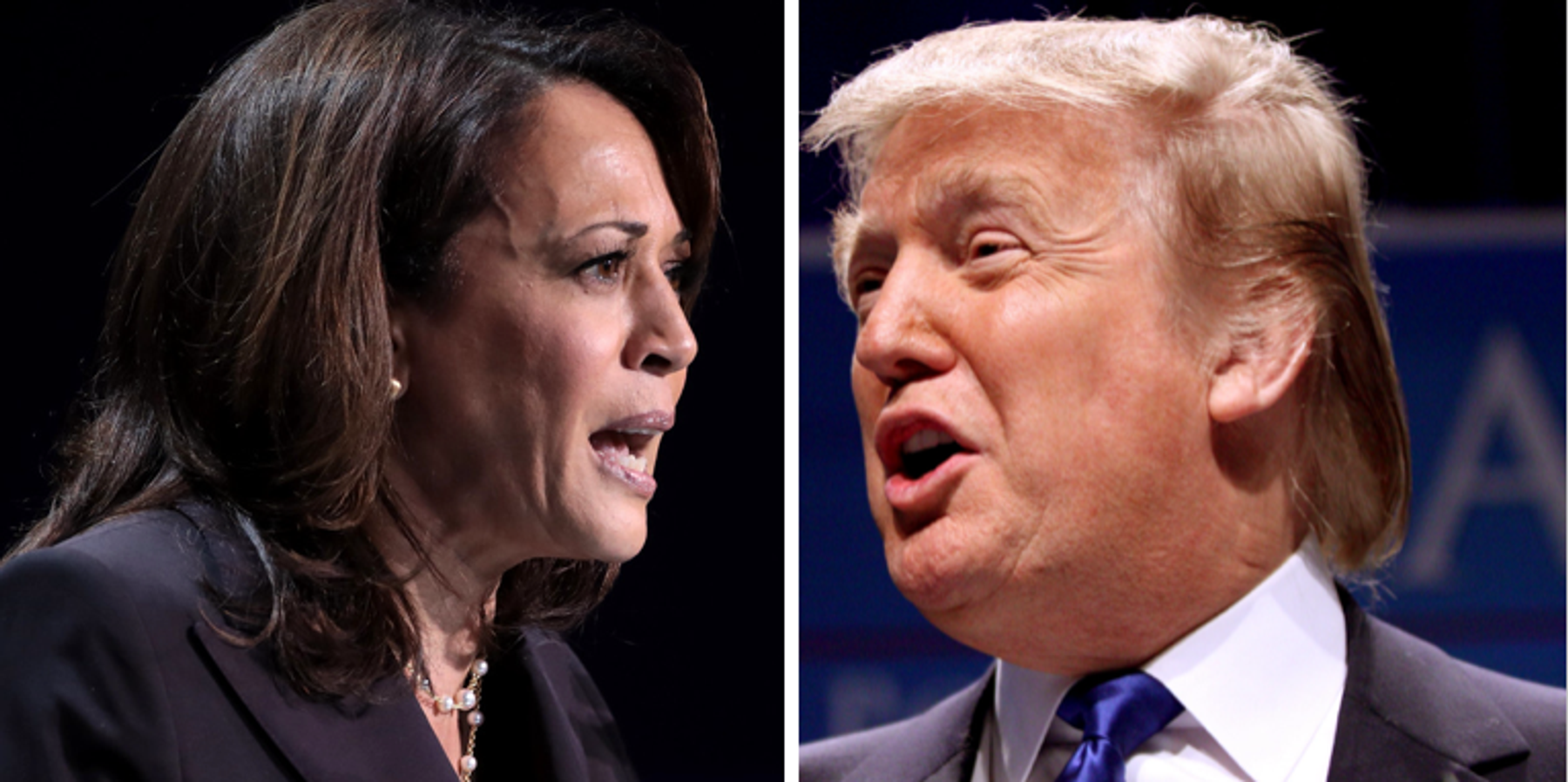

Democrats, backed by most of the mainstream media, would probably do their utmost to block and sabotage a Trump administration’s attempt at a peace settlement. Given the way U.S. politics now works, it is equally likely that Republicans would do the same to any such move by a Harris administration.

As the world’s foremost international power, the United States cannot afford such paralysis. If the war is not ended soon, the situation in Ukraine is likely to move rapidly towards a point where a U.S. administration will have only two choices. The first will be to acquiesce in Ukraine’s losing more and more territory (probably slowly and incrementally, as at present, but with the possibility of a sudden collapse), while its economy and infrastructure are ruined for the foreseeable future. The alternative will be to escalate towards direct war between the US and Russia.

It needs to be recognized that the combination of Ukrainian neutrality and a ceasefire along the present frontlines (as proposed by Senator J.D. Vance) would not “give Putin everything he wants,” as critics have charged. For Putin, this war is not primarily about conquering as much Ukrainian territory as he can. If that were the case, he would not have defied Russian nationalists by refusing for some eight years after the Maidan revolution in 2014 to approve bids by Ukrainian separatists in the Donbass to join Russia, which he feared would put the remainder of Ukraine on a path toward NATO membership.

Above all, Putin wants to neutralize the perceived military threat to Russia posed by NATO, and he wants to dominate Ukraine politically. But he cannot achieve those goals merely by force of arms. What we need to explore is how to establish a stable combination of military deterrence and diplomatic safeguards in Europe that will minimize the likelihood of NATO-Russia war, preserve Ukraine’s independence, and anchor its security within the European Union.

Is such an objective feasible? It is important to recognize here that while — according to opinion polls — a large majority of Russians are categorically opposed to anything that looks like Russian “surrender” in Ukraine, these polls also show that they are prepared to accept a peace settlement now, along existing lines. They do not want an indefinite war for complete victory (whatever that is), requiring vastly more sacrifices of lives and resources. Seeing that, Putin has indeed so far mobilized only a small fraction of Russia’s potential reserves.

Would Ukraine agree? There are certainly large numbers of Ukrainians who quite understandably do not trust that Russia would live up to commitments in any settlement deal, and many would prefer to continue fighting than acknowledge their hopes of regaining Ukraine’s 1991 borders are futile. But Ukraine’s military manpower is diminishing, and some polls suggest that growing numbers doubt Ukraine can recapture all Russian-occupied territory. In private, some recognize that governing and rebuilding Russian-occupied parts of Ukraine would be a formidable problem even if Ukraine were to regain them.

What about Europe? Enshrining Ukraine’s formal neutrality would reflect the reality that NATO governments, backed by the vast majority of their populations, have repeatedly stated that they will not go to war to defend Ukraine. This being so, NATO membership for Ukraine is an impractical idea, since it would require just this guarantee.

By contrast, European Union membership –— which Moscow has said it would support — would anchor Ukraine politically and economically in the West and put it on a path toward economic growth. It would also help to deter a repeat invasion by Russia, which would be reluctant to get into a war with EU members even if Ukraine lacked a NATO Article V security guarantee.

Moving Russia, Ukraine, and the European Union toward a mutually acceptable compromise that ends the war and stabilizes the region will be a formidable challenge. But it will be unthinkable if Washington itself remains at partisan loggerheads. Inter-party and intra-party conflicts will otherwise preclude both the sticks (in the form of continuing military support for Ukraine) and the carrots (in the form of easing sanctions) that will be necessary as leverage over Russia.

Such dissension will fuel doubts in Moscow that the United States would faithfully implement the terms of any deal. And it will tempt those in Ukraine and Europe who oppose any compromises to believe they can exploit America’s partisan dysfunction to block any negotiated settlement.

“Peace through strength” is a widely popular slogan in both the Republican and Democratic parties. But strength is not simply a function of military might. It also flows from faith in our own political resilience, the self-confidence required to strike pragmatic compromises with adversaries, and the moral courage necessary to put country ahead of short-term partisan advantage.

If we allow fear and dysfunction to preclude finding common ground at home on critical matters of national security, we can hardly expect to quell conflicts with our adversaries abroad.

- How can the war in Ukraine end? Let's count the ways. ›

- Is this the beginning of the end of the war in Ukraine? ›