In 1907, the then Siamese government signed over the provinces of Battambang, Siem-reap, and Sisophon to French Cambodia. The treaty outlined the new land and sea borders between French Cambodia and Siam — now Cambodia and Thailand, respectively — whose interpretation became a point of contention between the two countries in 1972. Since then, relations between the Thai and Cambodian governments over the disputed maritime territories have been amicable, but Thai nationalist group pressure has stymied recent attempts to resolve the issue.

With the establishment of the Chinese-funded Ream port in Cambodia, there is increasing concern that the port could be converted to military use to strengthen Chinese naval power projection or be a competitor to Thailand’s Eastern Economic Corridor. The port and secrecy around its actual use are reigniting concerns first established in the 1907 treaty, and inflaming Thai worries about what the port means for its maritime territories, the stability of the Gulf of Thailand, and relations with China and the United States.

Sovereignty and anti-colonialism in Thailand

Thailand was the only Southeast Asian country to retain its independence in the face of Franco-English great power competition in the 19th and 20th centuries. Until the late 1800s, Siam had expanded its control over Laos, Cambodia, and the Malayan states as tributaries, with parts of those regions being under varying legal and administrative control of Siam.

Siamese territorial borders were unclear to the French and English, and the extent to which each tributary could exercise its own autonomy varied widely. When the French and English began colonizing areas over which Siam had suzerainty, this increased pressure on Siam to define its borders and adopt the Western concept of sovereignty, eventually conceding territories and enacting unfair trade policies to maintain independence.

A major sore point of colonization was the 1855 Bowring Treaty with Great Britain, which granted significant, and arguably inequitable, trade privileges to the British in Siam. This was followed by the 1856 Franco-Siamese trade agreement, which closely mirrored the terms of the Bowring Treaty. Such trade agreements and other conciliatory policies were seen as necessary by then King Mongkut to maintain Siamese independence from great powers.

These factors contributed to the 1893 Franco-Siam Crisis, which ended Siam’s empire-building attempts and laid the groundwork for the loss of Laos, Cambodia, and the Malayan states. The last of these treaties was the Franco-Siamese Treaty of 1907, which established land and sea boundaries between Cambodia and Siam that have yet to be firmly determined by either country.

Once the absolute monarchy was abolished in 1932, a new national identity was formed on the basis of Thailand’s ability to maintain sovereignty and adherence to anti-colonialist concepts. Great power competition led to nearly a century of national humiliation for Thailand and has entrenched deep mistrust against overbearing foreign powers. With the secrecy around the Ream port and the potential for Chinese interference, Thailand is becoming apprehensive about the project and its potential to bring great power competition back into the Gulf of Thailand.

The implications of the Ream naval base on Thai sovereignty

Cambodia interpreted the maritime borders between Thailand and Cambodia in 1972 to include a greater chunk of territory for the Cambodians, creating an overlapping claims area of roughly 26,000 square kilometers that contains billions of dollars worth of untapped natural resources. If extracted, they would provide greater energy independence to either nation. Many experts consider these claims unique, even radical, in the field of international law. The Thai government rebutted the claims a year later, citing the original 1907 treaty.

In 2001, following regime changes and political upheaval in both Thailand and Cambodia, the two nations signed a Memorandum of Understanding that created a commitment to resolving the maritime disputes while creating a Joint Development Area in some parts of the disputed territory. Yet, political roadblocks within both nations prevented a lasting agreement. In 2024, the governments of both nations continue to discuss the best path forward, although they have been recently affected by Thai nationalist backlash.

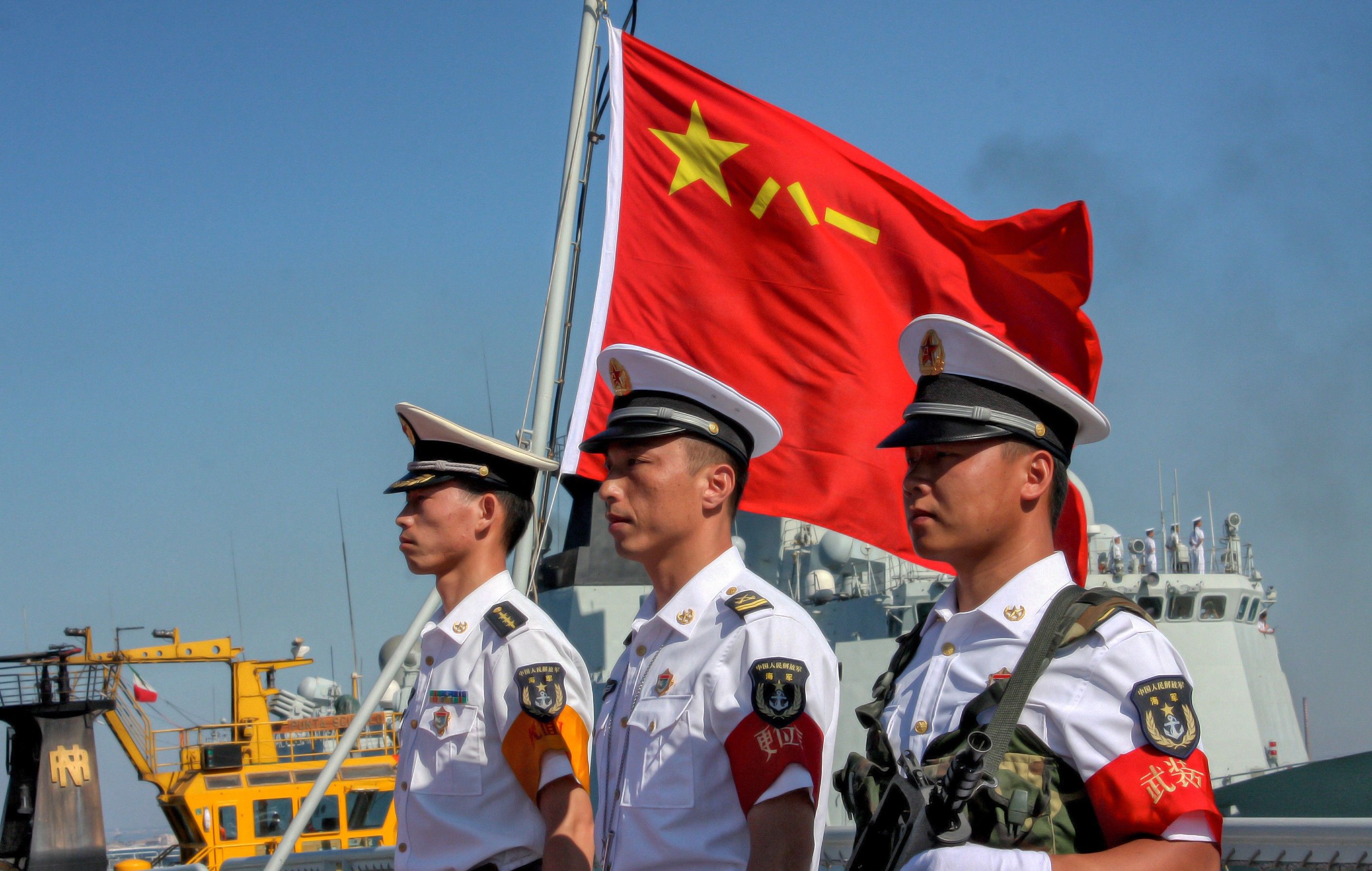

The historically friendly and compromising relationship between Thailand and Cambodia makes the Ream port a troublesome wedge between the two countries. China and Cambodia vehemently deny that the Chinese-funded port is operating covertly as an overseas base for the Chinese navy. Yet, satellite imagery shows the continued presence of Chinese warships while Cambodia continues to boost its military cooperation with China. Experts in the West and in Thailand have expressed concern over the potential for China to use this base to project its naval power in the crucial trade routes through Southeast Asia, possibly connecting it to the militarized Chinese ports scattered across the South China Sea.

For Thailand, the move is an unwelcome reminder of the country’s history with Franco-British great power competition over a century ago. With Cambodia modernizing its navy and receiving the backing of China, the overlapping claims area in the Gulf of Thailand could become a flashpoint between the two historically friendly countries. The Thai government is further concerned about the port because the areas immediately surrounding Ream have historically been strategically important. The French first constructed the nearby Port of Kampong Saom in 1955, choosing the location for primarily strategic means, including the solidification of French control over strategic waters between Thailand and Vietnam. During the Vietnam War, the Vietnamese communists leveraged the port to stockpile and transport military supplies along the Ho Chi Minh trail.

Furthermore, the region around the port does not lie on major traditional maritime trading routes, making Thailand even more dubious about its purpose given the secrecy around its construction. Thailand’s economy has already been negatively affected by the U.S.-China trade war, as approximately 25% of all Thai imports come from China, while around 15% of all Thai exports go to the U.S. Thailand has started to see China as a more reliable partner than the U.S., being geographically closer and more embroiled in the Thai economy, but still seeks to strengthen trade and military relations with the U.S. as a counterbalance. This is despite skepticism that the U.S. has an interest in Thailand beyond maintaining U.S. hegemony in East Asia. The construction of the Ream port, regardless if it were to serve as a military base or trading hub, may tip the scales further in favor of the Chinese regardless of Thailand’s desire to remain neutral.***

Thai government officials have expressed that the increasing influence of U.S.-China competition in the Indo-Pacific could pose a serious security threat if ignored. Many Thais, feeling the growing pressure of the rivalry, believe the best chance of maintaining true independence is through stronger relations with the middle powers, including Japan, Australia, and India.

As in the past, countries with superior military and economic might, countries with which Thailand has long sought to maintain good relations, are putting pressure on the nation to make a choice. Unfortunately, the echoes of Thailand’s past dealings with great power competition are becoming louder, originating with the 1907 Franco-Siam treaty and reverberating through to the Ream port. Thailand understands that it takes little time for great power competition to ignite greater conflicts, and the Ream port has the potential to be the spark that sets it off.