This article was republished with permission from the Nonzero Newsletter

This week President Biden, during his final address to the United Nations General Assembly, said the following about how the current conflict between Israel and Hezbollah began: “Hezbollah, unprovoked, joined the October 7th attack, launching rockets into Israel.”

This is only slightly misleading, but it’s misleading in an illuminating way—a way that helps explain Biden’s failure to end the carnage in the Middle East over the past year and also helps explain America’s failure to bring stability to the Middle East over the past few decades.

Here is how the year-long conflict between Israel and Hezbollah started:

Oct. 7: Hamas attacks Israel, intentionally killing many hundreds of civilians as well as hundreds of soldiers and police.

Oct. 7: Israel launches air strikes against Gaza, destroying numerous targets, including a mosque, and killing hundreds of Palestinians.

Oct. 8: Hezbollah strikes Israeli military posts in Shebaa Farms, a small, historically Lebanese patch of land that is not part of Israel under international law. Israel retaliates with strikes on Lebanon.

In the ensuing weeks and months, cross-border strikes on both sides expanded, and they have continued ever since.

Hezbollah explicitly said it struck Shebaa Farms as a show of sympathy with Hamas—so it’s fair for Biden to make a connection with October 7. Still, saying Hezbollah “joined the October 7 attack” makes it sound like Hezbollah collaborated in Hamas’s atrocities when in fact it’s unlikely that Hezbollah’s leaders even knew about the attack in advance, much less “joined” it.

Is this nitpicking? Here’s the case that it’s not:

1. Biden, as he spoke these words, was hoping that Bibi Netanyahu would sign on to a US-French proposal for a ceasefire between Israel and Hezbollah. Netanyahu is famous for resisting serious diplomatic engagement with adversaries, and he typically justifies this resistance by depicting them as the incarnation of evil. If Biden really wanted a ceasefire, why embrace the kind of exaggerated rhetoric Bibi had used to resist it? Wasn’t he making Netanyahu’s recalcitrance easier by endorsing its supporting narrative?

2. Netanyahu says he has escalated attacks on Lebanon so dramatically over the past two weeks because he must do “whatever it takes” to end Hezbollah’s missile fire so that Israelis evacuated from the northern part of the country can return to their homes. But, as Hezbollah has made clear all along, all it would take to end the firing of missiles into Israel is for Israel to end its war on Gaza. Biden’s description of the motivation for Hezbollah’s attacks obscures this conditionality and so, however slightly, reduces the pressure on Netanyahu to end the Gaza war, something Biden claims to want.

What’s more: Though the ceasefire with Lebanon proposed by the US and France would have entailed a ceasefire in Gaza, the attendant commitments would have lasted only three weeks—which means none of Israel’s stated reasons for resisting a longer Gaza ceasefire would apply. (Israel wouldn’t, for example, have to withdraw troops from the Philadelphi Corridor, between Egypt and Gaza.) Why, when Biden had the biggest megaphone available to anyone this week—the podium at the UN General Assembly—did he not convey how little the US and France were asking of Israel and so put some pressure on Netanyahu? Why did he do the opposite by describing Hezbollah’s attacks exactly as Netanyahu would have wanted?

Two decades ago, Aaron David Miller, a veteran US negotiator, lamented that American officials—including, he admitted, himself—had habitually acted as “Israel’s lawyer” rather than as an honest broker between it and its adversaries. He was referring to formal negotiations with the Palestinians, such as the Camp David talks of 2000, but the fact is that this basic tendency has infused American dealings with Israel more broadly. American presidents and their staffers, in describing Israel’s situation, reflexively parrot Israeli talking points. And, as Miller suggested, this doesn’t serve Israel’s long term interests (much less America’s interests) even if it does serve the political interests of whoever the prime minister is at the time.

Even over the past year, as Israel has killed 1 in 50 Gazans—and at least 1 in 100 Gazan civilians—the Biden administration, while saying it wants peace, has described Israel’s situation in a way that puts no pressure on Netanyahu to create it. A typical interaction with reporters by national security spokesman John Kirby or state department spokesman Matthew Miller involves reminding them that Hamas started the war, reminding them that Israel has a right to defend itself, and noting one or two ways Hamas is worse than Israel. Then, often, there is a ritual lamentation of “the suffering” in Gaza—as if “suffering” were some autonomous metaphysical force that mysteriously visits unfortunate parts of the world, rather than something delivered by bombs the US gives Israel.

This basic pattern has persisted for decades. The US gives Israel weapons, and it kills whoever it wants wherever it wants, regardless of the consequences for regional stability and regardless of any international or national laws violated in the process. And the US, like a good lawyer, describes the context for the attacks in ways that seem to justify them. Today’s Israeli strike targeting Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, which brings the Middle East appreciably closer to full-scale regional war, is in part the product of many years of this kind of positive reinforcement.

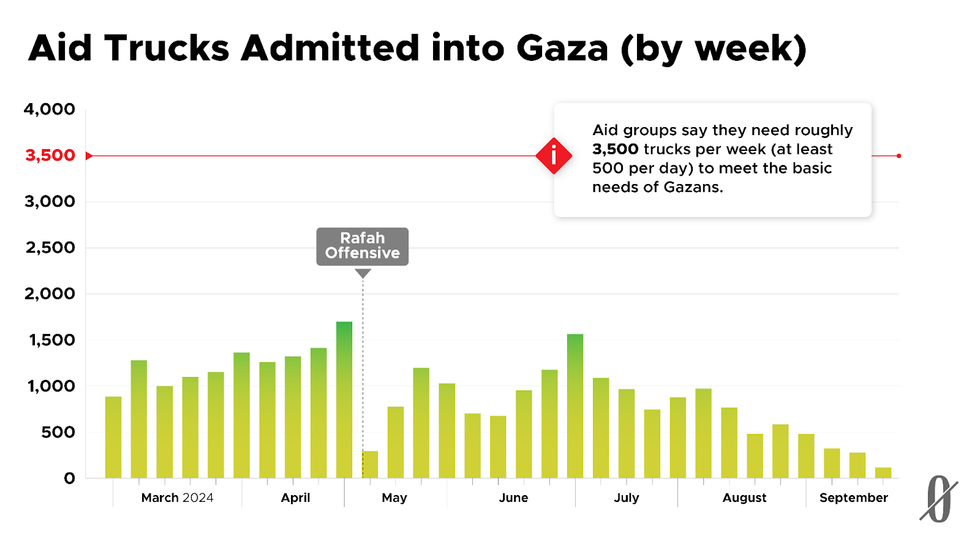

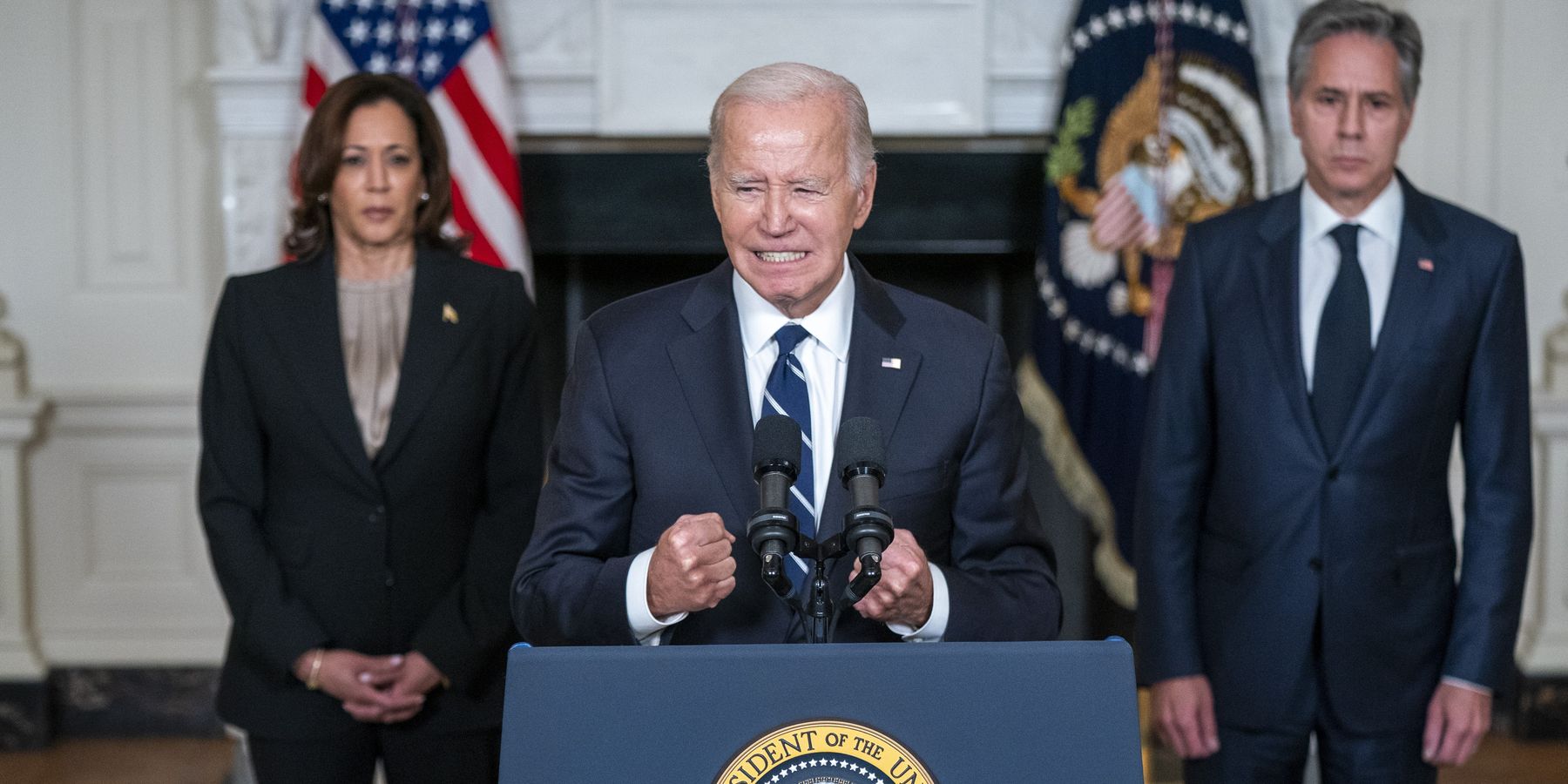

Speaking of national laws that get sacrificed in the name of Israel: This week ProPublica reported that, back in April, Secretary of State Antony Blinken ignored two Biden administration reports finding that Israel was blocking US aid from getting into Gaza—findings that, according to US law, should have led Washington to end weapons exports to Israel. The reports came from USAID and the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration, the government’s leading authorities on humanitarian aid. Though Blinken was aware of both reports, he chose to certify Israel’s compliance with the law, telling Congress in May that “we do not currently assess that the Israeli government is prohibiting or otherwise restricting the transport or delivery of US humanitarian assistance.”

This, according to Sarah Harrison, a former Pentagon lawyer, was par for the course. “This was my experience in government,” she wrote. “If bureaucrats determined Israel’s actions triggered US law restricting the transfer of arms, political leadership would ignore them. It didn’t matter that the civil servants writing the memos were the most informed on these issues.”

Blinken’s decision came at a critical moment. Israeli forces had just seized a crossing in the southern city of Rafah, closing a key entry point for humanitarian aid. The Biden administration hoped to stop a full-scale assault on Rafah, where many displaced Gazans had sought refuge. But Blinken’s statement amounted to a green light for Israel, and four days later Israeli forces began an offensive that displaced one million Gazans and damaged or destroyed more than 40 percent of the buildings in Rafah.

As hostilities in Lebanon escalated this week, some friends of Israel expressed grave concern. (Check out the levels of alarm and despair in this Tom Friedman column.) That’s not because Israel may “lose” the war. Indeed, its military dominance over all regional enemies has now been demonstrated so thoroughly as to undermine its description of them as existential threats. If there’s an existential threat to Israel, it’s a much longer term threat, and its seeds lie in Israel’s reflexive preference for short-term military victory over far-seeing diplomacy. Nobody has done more to encourage and reinforce that reflex than Israel’s American lawyers—including, most recently, Joe Biden and Antony Blinken.

They may be blissfully unaware of this paradox, but this week we found out that there’s at least one headline writer at the Washington Post who isn’t numb to irony: “Biden touts his record at U.N. as Mideast violence erupts.”

- Biden OKs more arms to Israel, crushing hope of Gaza shift ›

- By caving to Israel, Biden opens the door to war ›

- Blinken's sad attempt to whitewash Biden's record | Responsible Statecraft ›

Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org