We all know that the U.S. spends obscene sums of money on defense. But the actual amount tends to be a moving target, one that is described by official Washington and its enablers in the media in the smallest terms possible.

Thus in unveiling the Pentagon’s 2024 budget request on March 6, DoD Comptroller Mike McCord demurely highlighted $842 billion as the “top line” a figure dutifully cited in relevant news reports. In his remarks, McCord took pains to remind us that, actually, we’re spending much less than we used to: “When I was born [1959] we, the United States, were at nine percent of GDP on defense. Ronald Reagan was considered high at six percent. We're now at three. So it's a big number, but in other contexts, you know, you could look at it another way.”

So what do we actually spend on the defense of the United States? Unearthing the true figure demands tireless application combined with a sure grasp of the subterranean pathways along which our dollars travel to fuel the national security machine.

Fortunately, we can spare ourselves the effort, thanks to the work of defense analyst Winslow Wheeler. Wheeler learned his budget-navigator’s skills over many years in the congressional branch of the military industrial complex in assorted U.S. Senate offices, including the budget committee and the staffs of both Democratic and Republican senators, before transitioning to the GAO and then the watchdog Center for Defense Information. He had now applied his hard-won knowledge to our current and imminent outlays. As he tells us:

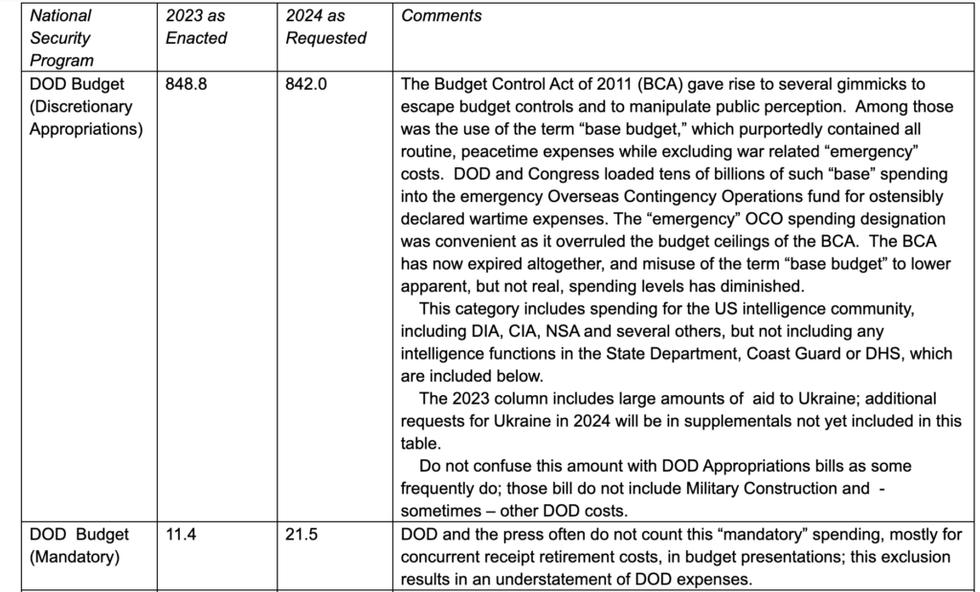

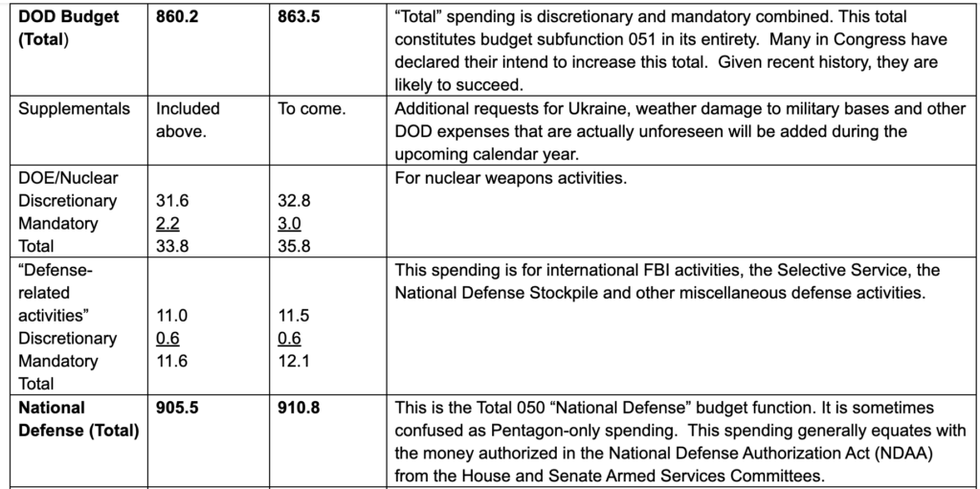

“The big spenders, especially, like to distort the size of our spending — and to mis-measure it -— with gimmicks and yardsticks that have almost nothing to do with dollars spent. As it did in the past, this has prompted me to put together a table showing all the spending that goes into US national security for the current and next fiscal years.

Some can’t even get Pentagon spending right (usually intentionally, I believe) by undercounting it. Others ignore enormous and entirely relevant amounts outside the budget of the Department of Defense — such as for nuclear weapons, protecting the homeland from terrorists and other criminals, or international security. One should also include a fair share of the costs that this spending adds to the annual deficit.”

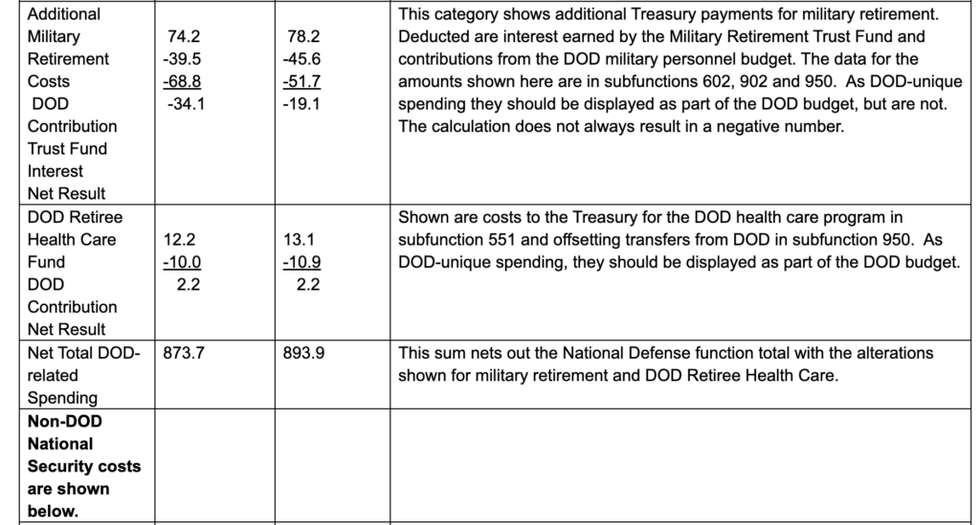

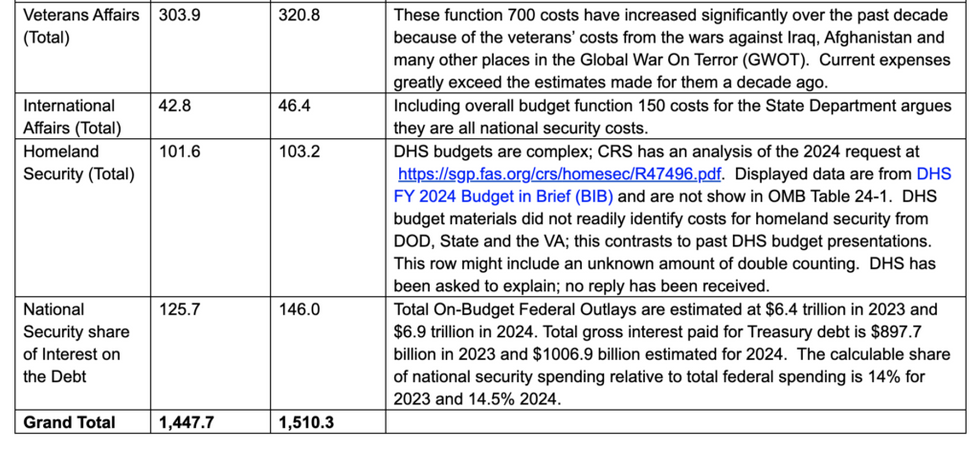

His findings are laid out in the table below, sourced mainly from OMB's presentation materials for the 2024 budget request.

Spoiler alert: The number is much, much, bigger than they want you to know.

The column labeled "Comments" offers descriptions of just what monies are included, or not, in each category, plus some discussion of past and present gimmicks used to manipulate the public's perception of the "defense" (or "national security") budget.

- Another year, another delusional Pentagon budget request | Responsible Statecraft ›

- The Pentagon keeps failing up — on your dime | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Will military budget boosters ever say 'when'? | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Military slammed by new mold revelations in military housing | Responsible Statecraft ›

- $200 billion more for the Pentagon? | Responsible Statecraft ›

- GOP lawmakers question endless military spending | Responsible Statecraft ›

- The Pentagon spent $4 trillion over 5 years. Contractors got 54% of it. | Responsible Statecraft ›

- The reality of Trump’s cartoonish DOD budget proposal | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Could the US win a war with a near-peer adversary today? | Responsible Statecraft ›