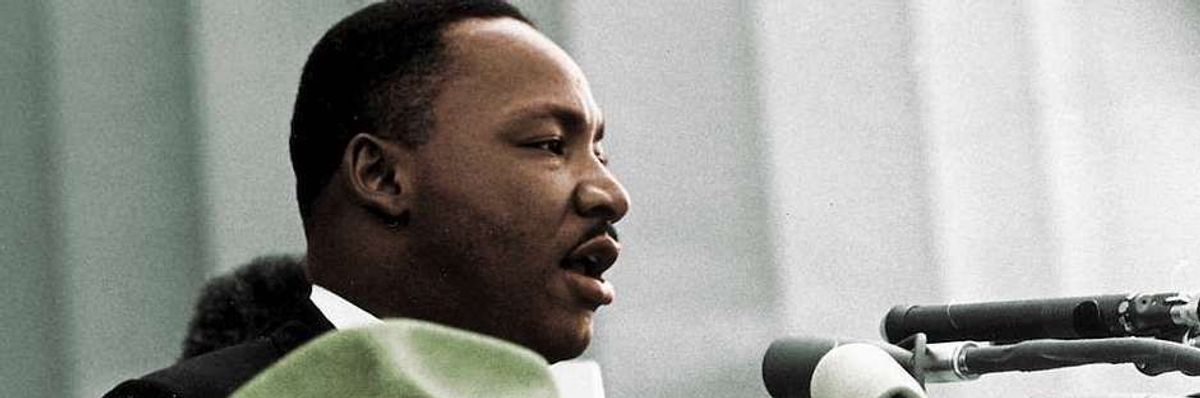

The birthday of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. provides an opportunity to step back and reflect on the significance of his life and work. It is particularly important to do so this year, with unapologetic racism on the rise and a Cold War atmosphere permeating Washington.

Dr. King had a deep understanding of the links between America’s domestic and foreign predicaments, expressed most clearly in his speech against the Vietnam War, delivered at New York’s Riverside Church on April 4 1967, one year before he was assassinated.

King understood that Vietnam was not an isolated case of U.S. military adventurism:

The war in Vietnam is but a symptom of a far deeper malady within the American spirit, and if we ignore this sobering reality… we will find ourselves organizing "clergy and laymen concerned" committees [like the one against the war in Vietnam] for the next generation. They will be concerned about Guatemala — Guatemala and Peru. They will be concerned about Thailand and Cambodia. They will be concerned about Mozambique and South Africa. We will be marching for these and a dozen other names and attending rallies without end, unless there is a significant and profound change in American life and policy.

King’s predictions about where the United States would intervene were not accurate, but the process he described has all too sadly played out, from Afghanistan to Iraq to Libya to Somalia to Syria and beyond.

These direct interventions don’t take into account America’s role as the world’s leading arms trading nation, supplying equipment to countries like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates that have been used in a brutal war in Yemen that has led to direct and indirect deaths approaching 400,000 people. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, the United States supplied weapons to 103 nations between 2017 and 2021 — more than half the countries in the world. For many citizens of the world, their first association with America is a U.S. soldier or a U.S.-supplied weapon in the hands of their government or one of their adversaries.

This U.S. record of wide-ranging military intervention and runaway arms sales is a far cry from the “diplomacy first” foreign policy that the Biden administration has pledged to pursue. To its credit, the administration stuck to its commitment to get the United States out of its disastrous 20-year engagement in Afghanistan. And in some cases, as in Ukraine, U.S. arms have been supplied for defensive purposes, to help Kyiv fend off a brutal Russian invasion. But on balance, the United States still adheres to the kind of militarized foreign policy that Dr. King warned us about well over 50 years ago.

Quincy Institute non-resident fellow and Tufts University professor Monica Toft has noted the broader impacts of America’s addiction to military force in a recent piece in Foreign Affairs:

This is an unfortunate trend. For evidence, look no further than the disastrous U.S. military interventions in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya. The overly frequent resort to use of force also undermines U.S. legitimacy in the world. As the U.S. diplomatic corps and American influence abroad shrink, the country’s military footprint only grows.

Toft also points to the impact on U.S. interventionism on the reputation of America in the world. A Pew research poll conducted between 2013 and 2018 found that the number of foreigners who considered the United States a threat nearly doubled over that time period, from 25 percent to 45 percent.

King also underscored the domestic consequences of rampant interventionism:

A few years ago there was a shining moment in that struggle. It seemed as if there was a real promise of hope for the poor — both black and white — through the poverty program. There were experiments, hopes, new beginnings. Then came the buildup in Vietnam, and I watched this program broken and eviscerated, as if it were some idle political plaything of a society gone mad on war, and I knew that America would never invest the necessary funds or energies in rehabilitation of its poor so long as adventures like Vietnam continued to draw men and skills and money like some demonic destructive suction tube.

The domestic costs of militarism are painfully present today. The budget signed by President Biden last month provides $858 billion for the Pentagon and related work on nuclear weapons at the Department of Energy. That’s well over half of the federal government’s entire discretionary budget — the portion that includes virtually everything the government does other than mandatory entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare: environmental protection, public health, administration of justice, job training, education, and more. Meanwhile Congress has resisted the administration’s attempts to get additional funding for Covid relief, and terminated the Child Tax Credit, one of the most effective means of eliminating poverty.

King understood that the roots of the warfare state run deep, driven by the “giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism.” Groups like the Poor People’s Campaign, co-chaired by Rev. William Barber and Rev. Liz Theoharis and inspired by Dr. King, have taken up the call to address these issues. More groups and individuals need to do so if we are to foster a genuine “diplomacy first” foreign policy, with the immense benefits for American and global security and prosperity and equality at home that would entail.