It has been four years since the murder of Saudi dissident and Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul at the order of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The gruesome assassination placed pressure on institutions and governments with ties to the kingdom to rethink their association. Among them were American universities, which had accepted millions of dollars from Saudi Arabia to establish and support research centers, create fellowships, pay tuition, and pursue partnerships. Yet, despite pressure to rethink their Saudi ties, funding from the kingdom to U.S. universities has actually increased since Khashoggi’s murder.

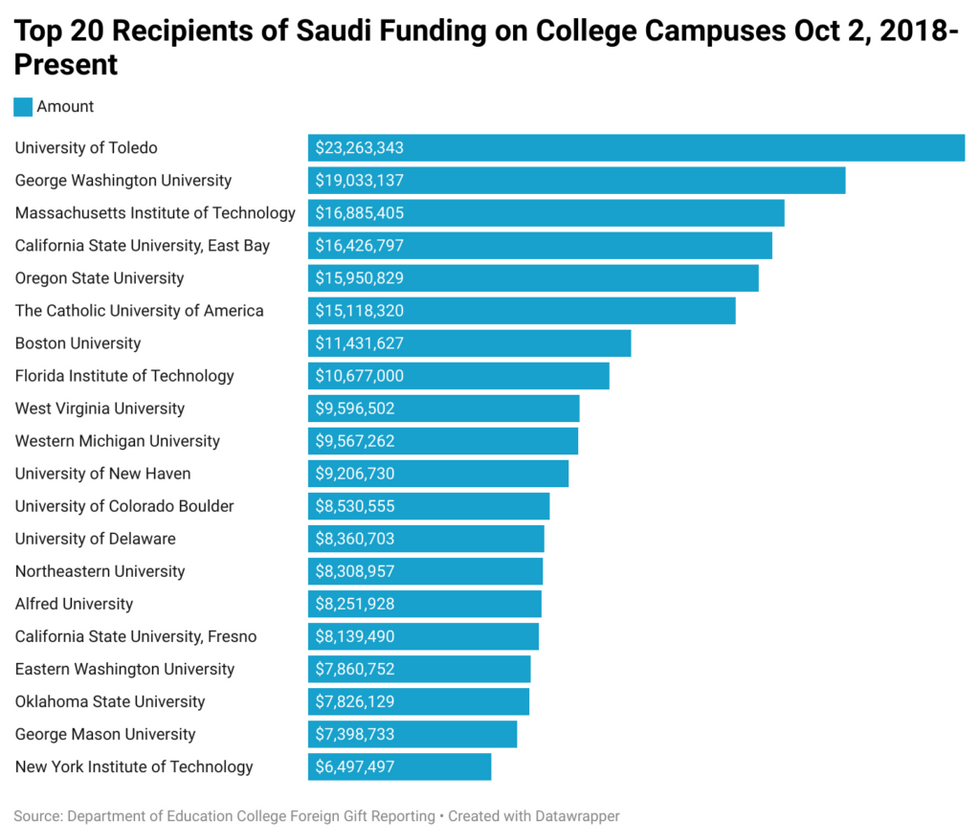

An analysis of Department of Education records reveals that Saudi Arabia remains one of the largest sources of foreign funding of American universities. In 2019, Saudi donors gave more than $270 million to these institutions, up from $165 million the year before. All told, since Khashoggi’s murder, 144 of America’s colleges and universities have accepted a combined $440 million in Saudi funding. The chart below indicates the top 20 recipients of Saudi money across college campuses in that time period:

These figures don’t take into account contracts that started after Khashoggi’s murder but have not been paid out, a gargantuan figure that totals nearly $700 million.

These figures reveal that once the spotlight of Khashoggi’s murder had moved on, university administrators quietly continued taking the kingdom’s checks.

Among the universities that gave second thought to their association with the kingdom was the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, one of the largest recipients of Saudi largess. MBS had visited MIT, where he was met with protests, just months before Khashoggi’s murder. His entourage included Maher Mutreb, who, according to the U.S. government, “coordinated and executed” the operation to kill Khashoggi.

In response to the murder, MIT called Khashoggi’s disappearance a “grave concern” and launched a formal review of its partnership with Saudi Arabia.

But that’s all it was: a review. When the formal inquiry came out a few months later, it acknowledged the “disturbing sense of connection between the killing in Istanbul and the MIT campus” through Mutreb’s presence, but the school ultimately decided against severing ties with the kingdom. It even went a step further by including a section titled “possible new engagements.” MIT president L. Rafael Reif circulated an email explaining the decision:

“I know many of you find the behavior of the Saudi regime so horrifying that you believe MIT should immediately sever all ties with any Saudi government entities…However, my experience leads me to see our Saudi engagements differently, and therefore to believe that cutting off these longstanding faculty-led relationships abruptly in midstream is not the best course of action.”

By the report author’s own admission, a majority of faculty who commented were “strongly opposed” to this recommendation. Jonathan A. King, an emeritus professor of biology at MIT, said that the university's arrangements were “driven not by intellectual content but by money.”

Since then, MIT has accepted nearly $17 million from Saudi Arabia, according to Department of Education records.

In an email to Responsible Statecraft, a spokesperson said that MIT continues to follow its enhanced review process “for considering proposed engagements with people or entities in several countries, including Saudi Arabia.” The other two countries are Russia and China. After introducing this process in early 2019, MIT decided it would not renew Saudi Aramco’s membership in MIT’s energy research center in fall of 2020.

MBS had also visited Harvard University, another major recipient of Saudi funding, on the same trip. Harvard’s student newspaper The Crimson, pleaded with its administration: “By associating itself with the Saudi regime, Harvard – one of the best universities in the world – runs the risk of legitimising both the authoritarian nature of the regime and the brutal policies it carries out abroad.”

At the time, a Harvard spokesperson said the university was “following recent events with concern,” and “assessing potential implications for existing programs.” Since then, Harvard has agreed to over $8 million worth of gift contracts from Saudi Arabia which have not yet been paid out, the vast majority of which started in 2020 and 2021.

Harvard did not respond to a request for comment.

MBS might not be receiving invitations to visit MIT and Harvard anymore, but these universities continue to accept checks from the kingdom. Across the United States, Saudi Arabia remains one of the largest foreign funders of education.

At least one key university tie quietly fizzled out. In 2016, the Henry C. Lee College of Criminal Justice and Forensic Sciences at the University of New Haven signed a partnership with King Fahd Security College, a police college based in Riyadh. Under the agreement, experts from UNH would advise their Saudi counterparts on criminal justice, homeland security, and intelligence studies. “We are excited to put the University of New Haven's world-renowned programs in criminal justice, national security, and forensic science studies at the service of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia's next generation of security professionals,” said UNH’s president at the time.

After Khashoggi’s murder, the UNH-King Fahd partnership came under scrutiny as questions were raised about a potentially damaging connection; Saleh al-Tubaigy, the man believed to have carried out the assassination, served on the editorial board of the journal produced by King Fahd Security College alongside Henry C. Lee. The university responded by claiming it was a different al-Tubaigy, though his name was quietly scrubbed from the editorial board website. (He seemingly still sits on the board committee). “We don’t teach them torture or kidnapping,” Lee, the criminologist who the college is named after, assured his critics.

The contract ended in 2021. When asked by Responsible Statecraft why it wasn’t renewed, the College’s assistant dean, Daniel Mabrey, didn’t mention Khashoggi. “It was a fixed term contract,” he said. “The work was completed. All deliverables were made. It was the middle of a pandemic. There was no need to renew.”

There is recent precedent for these universities re-evaluating their relationship with governments engaged in human rights abuses. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, MIT cut ties with a research university in Moscow that it helped establish. In a statement, Reif said “this step is a rejection of the Russian government in Ukraine.” Similarly, Yale University, a top destination for Saudi largess that boasts a law center funded by Saudi businessman Abdallah S. Kamel, ended a partnership with a business school in Russia in March of 2022.

Saudi Arabia has a lot to gain from funding American universities. According to Michael Sokolove, a contributing writer to the New York Times Magazine, “the entree to schools like M.I.T. serves to soften the kingdom’s image. Saudi Arabia is an absolute monarchy, hostile to women’s and L.G.B.T.Q. rights and without protections for a free press or open expression, but its associations beyond its borders can make it seem almost like an honorary Western nation.”

Raed Jarrar, the Advocacy Director at Democracy for the Arab World Now, told Responsible Statecraft that the increase in Saudi funding at U.S. universities is coming more because of Jamal Khashoggi’s murder rather than despite it. “The Saudi government, especially MBS, is aware that they are in trouble,” he said “Their solution to the fallout and subsequent public relations crisis of their murder of Jamal Khashoggi is to throw money at it rather than holding those behind the assassination accountable.”

Saudi influence in American higher education is also a key part of the kingdom’s larger influence operation in the United States that also includes lobbying, public relations, sportswashing, and even cultivating ties with Hollywood and the entertainment industry. In fact, Saudi lobbyists sometimes communicate directly with the universities that receive Saudi funding and were keen to share press surrounding MBS’s trip to MIT.

Saudi Arabia’s latest foray, cutting oil production along with the rest of the OPEC+ oil cartel by two million barrels per day, is unlikely to change university administrators' minds about taking checks from the kingdom.

“If the universities didn’t stop taking money after Khashoggi’s murder, the war in Yemen, the blockade of Qatar, and all of the atrocities at home and abroad, they are not going to stop for anything at all,” said Abdullah Alaoudh, Research Director for Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates at DAWN.

Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org