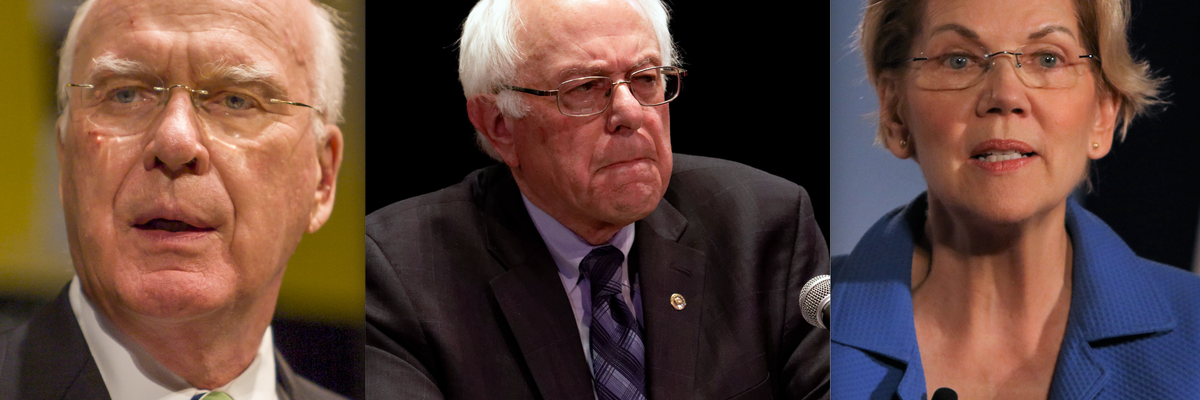

Sens. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), and Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) introduced a joint resolution on Thursday aimed at ending the unauthorized U.S. military role in the Saudi-led coalition’s war in Yemen.

The move comes amid President Biden’s unpopular visit to the region, where he will visit with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in the coming days. In an op-ed explaining the reasoning behind the trip, Biden touted an ongoing truce in Yemen, but didn’t say whether he would press for an end to the war.

The House introduced a similar bill last month led by Reps. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) and Peter DeFazio (D-Ore.). The senate companion will be considered “privileged,” meaning it can be voted on 10 calendar days after it is introduced.

“We must put an end to the unauthorized and unconstitutional involvement of U.S. Armed Forces in the catastrophic Saudi-led war in Yemen and Congress must take back its authority over war,” Sanders said in a press release. “More than 85,000 children in Yemen have already starved and millions more are facing imminent famine and death.”

Sen. Warren noted that “The American people, through their elected representatives in Congress, never authorized U.S. involvement in the war,” adding that “Congress abdicated its constitutional powers and failed to prevent our country from involving itself in this crisis.”

“The U.S. must immediately end its support for Saudi-led coalition in Yemen unless explicitly authorized by Congress,” she said.