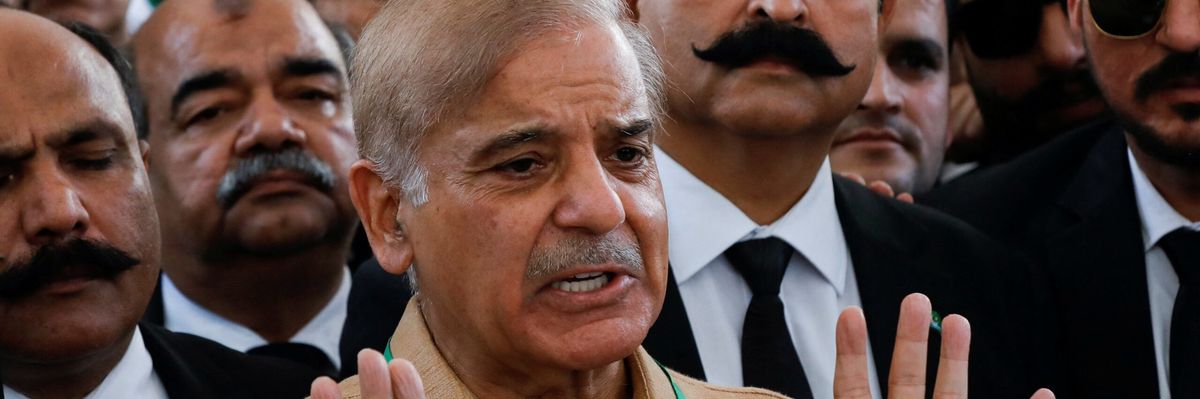

Shebaz Sharif, the younger brother of three-time prime minister Nawaz Sharif, takes over a politically divided Pakistan as terrorist attacks are rising, the economy is in crisis mode, and Shehbaz himself faces a deferred indictment for money laundering.

Sharif was elected prime minister by Pakistan’s National Assembly on Monday after Imran Khan was removed from office through a vote of no confidence last weekend.

Opposition parties saw worsening relations between Imran Khan and the military as an opportunity to strike and this catapulted Shehbaz into the prime minister’s office. He is known as a competent administrator, but not a charismatic politician like his brother. Shehbaz has pledged to heal Pakistan’s divisions and reach out to those who have been stigmatized in the political discourse. But he also faces an electrified demographic that vehemently supports Imran Khan and feels sidelined by the change in government. He will have to deliver fast on the economy or Khan’s problems will become his own.

He also assumes office at a time when U.S.-Pakistan relations are frosty at best. Pakistan doesn’t quite fit into the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy and Washington’s focus on Afghanistan and Pakistan from a security perspective is waning. President Biden never called Imran Khan as prime minister, which was a point of frustration for Khan and his advisors. It will also politicize any future communication between Biden and Sharif which will be used by Khan’s supporters as evidence of U.S. favoritism and meddling in domestic affairs.

However, U.S.-Pakistan security relations will continue to be primarily managed through Pakistan’s security establishment. These relations are more likely to be impacted by whether the army chief General Qamar Bajwa seeks an extension in November than the country’s civilian politics.