It was hard not to notice the odd congruence between the recent passing of a grand dame of American foreign policy, the venerable Madeleine Albright, and President Biden’s apparently off script remarks in Poland that questioned whether Vladimir Putin should remain in power.

While his remarks were walked back by the White House and Secretary of State Anthony Blinken, he stood by them in principle a day later. Indeed, Biden’s formulation can’t just be taken back. We can’t pretend that he didn’t make his statements, which raise the stakes in Ukraine to even more dangerous proportions than already exist.

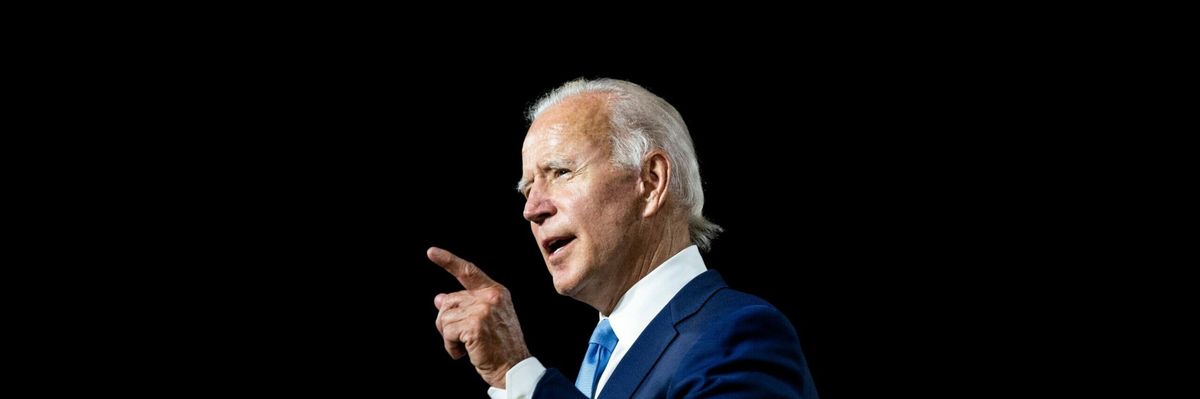

It was almost as if Albright’s spirit had surrounded Biden during his fiery, jingoistic speech in Poland. The president emphatically denounced yet another despicable dictator that represented a broader contest between good and evil in the international system that had to be taken up by the United States as the protector of the moral, the just, and the good.

His speech took me back to March 1997 when then Secretary Albright announced that the United States would be seeking “regime change” in Iraq, convinced that Saddam could not be allowed to remain in power.

At the time, I was the country director for Iraq in the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Policy, and the speech made no sense to me. Why would the United States seek regime change in a country if it wasn’t prepared to commit the resources necessary to invade the country and change the government? Of course that would come later. Moreover, I had to wonder how Iraq, one of the poorest countries in the world, could be cast as such a broad threat to international peace and security.

Of course, the 1990s was an era of the so-called “rogue” states that Albright and others had warned represented a systematic threat to the U.S.-dominated post-Cold War order. These “rogue states” had replaced the Soviet Union as the boogie-men of the international system that were successfully seized upon by Colin Powell and others in the Defense Department to limit cuts to their force structure and budgets. In retrospect it was a strategic misdirection of the highest order.

Following Albright’s speech, we got something called the Iraq Liberation Act, in which a collection of neoconcervative figures convinced Congress and the weak-kneed Clinton administration to formalize regime change in law. The result was that we started supporting Ahmed Chalabi and his cronies in London’s expensive West End with our tax dollars.

What went unrecognized at the time was the descent down a slippery slope for U.S. strategy and policy as we, the United States, presumed in our ever-present exceptionalism, to be the judge, jury, and executioner in deciding who should rule and who should not. It was, of course, a vast overreach of epic proportions that would come back to bite us in the post 9/11 era when we took on the moral crusade in earnest against Jihadi terrorists across the Middle East and South Asia.

Albright served as the vanguard of the liberal internationalist wing of the Democratic Party, which argued forcefully that U.S. military power should be used for moral purposes to right the wrongs of dictators like Saddam Hussein and Slobodan Milosevic. One could just as easily insert Vladimir Putin into this mix — as Biden did in Poland. Albright and her colleagues left a powerful legacy that regrettably crowded out the more cautious realist-oriented approach to U.S. foreign policy that had dominated most of the Cold War.

In the post 9/11 era, the liberal internationalists joined up with the neoconservatives to bring us regime change in Iraq and the attempt to re-engineer the politics of both Iraq and Afghanistan along Western lines. The toxic mix of these approaches to foreign policy drove a 20-year period of mostly disastrous military interventions around the world as we declared the dawn of the global battlefield, with the right to blast away wherever we wanted against whomever we deemed to be on the wrong side of the law — due process be damned.

As evidenced by Biden’s speech, Albright’s legacy and the arguments about good vs. evil and using force for moral purposes, remain powerful forces in American foreign policy today. Biden, of course, chaired the Senate Foreign Relations Committee during the 1990s and remains steeped in the era’s legacy. The lesson drawn seems to be something like: we should stand up to despotic dictators wherever they may be — calling them out for what they really are but with no real appreciation on how to connect ends, ways, and means with the lofty rhetoric.

The lessons of Iraq strangely seem lost in the current era — in which we gradually slipped down the slope from stand-off bombardment to a disastrous military occupation to no strategic purpose. This sets aside the massive intelligence failure that surrounded Saddam Hussein himself and his motivations for convincing the West that he remained armed to the teeth with his WMD programs. Instead we allowed our hubris and sense of exceptionalism to guide decision-making to disastrous effect for us and the thousands of Iraqis that perished or fled to refugee camps. And yet today the airwaves are rife with commentators purporting to know all about Putin’s motivations in launching the invasion of Ukraine.

Biden’s speech in Poland might have made the late-Madeleine Albright happy, but it remains unclear that casting the world in simplistic, moral terms represents a sound building block to guide strategy and foreign policy for determining when and under what circumstances we should go to war.