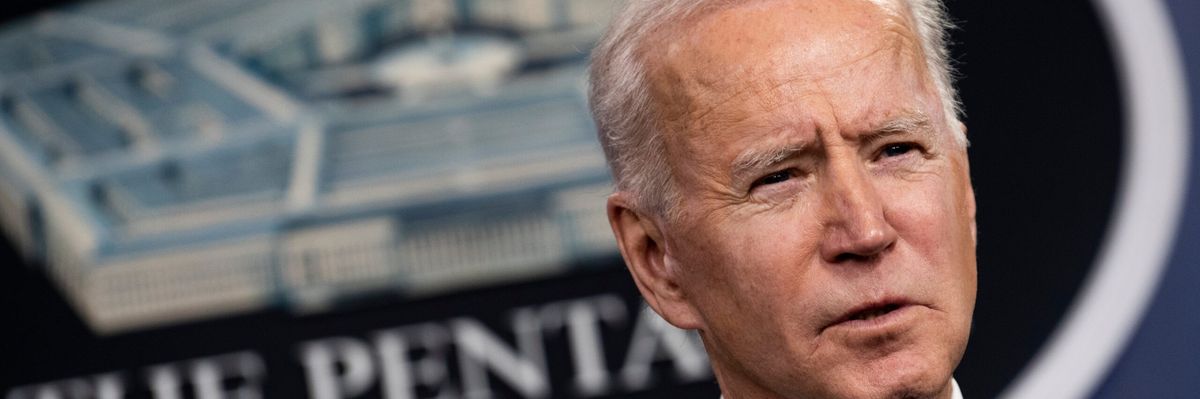

President Biden took a remarkably different approach than former President Trump when the two faced off on the 2020 presidential campaign trail, both in style and in substance. You would hardly know the difference between the two, though, solely based on the $777 billion defense policy bill President Biden signed into law two days after the Christmas holiday.

Organizations representing both progressive interests and more fiscally conservative perspectives had urged President Biden earlier this year to pull back on the huge defense budget increases that occurred during former President Trump’s four years in office. From the defense budget just before President Trump took office (fiscal year 2017) to the last one Trump signed into law (FY 2021), Department of Defense spending grew a staggering $98 billion, (or 16 percent). The DoD’s budget grew by $65 billion in Trump’s first year (+10.7 percent), $17 billion in his second year (+2.6 percent), and $35 billion (+5.1 percent) in his third year, before shrinking $19.5 billion (-2.7 percent) in his final year. What’s worse, that big $65 billion budget increase (and the $25 billion increase in President Obama’s final budget for fiscal year 2017) were approved by Republican majorities in both chambers of Congress, despite the GOP’s professed concern for fiscal responsibility.

As noted above, experts and advocates across the ideological spectrum were hoping President Biden would assume some leadership in advocating for a reduced defense budget relative to the Trump years. Biden would surely experience resistance from the defense hawks in Congress in both parties, the thinking went, but he could give this reduced, more sustainable defense budget a major boost with Congress by advocating for it within the president’s annual budget request.

Unfortunately, President Biden’s first defense budget request was largely unambitious, and effectively held spending flat relative to former President Trump’s final year in office. At the very least, the first Biden budget request did not advocate for major increases to the defense budget, unlike President Trump and his first defense budget.

Based on the reaction from major military boosters in Congress, though, you would have thought the sky had fallen. Republicans called the budget request “reckless” and even “dangerous.” A dozen Senate Democrats on the Armed Services Committee voted this summer to fatten up Biden’s budget request by $25 billion, with only Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) having the courage to vote “no” on tens of billions of dollars more for the military and the contractors that support it.

And so the defense policy bill President Biden signed into law this week authorizes $740 billion in spending on the military (along with an additional $27 billion for nuclear weapons under the Department of Energy, and $1o billion for "miscellaneous defense needs"), $25 billion more than President Biden’s $715 billion budget request and $36 billion more than the $704 billion spent on the military in the last fiscal year. This larding up of the defense budget is happening even as the U.S. has ended major military operations in Afghanistan, and even as Congress is dedicating separate emergency funds to resolving the catastrophes that arose there.

The press releases from your Senator or member of the House will talk about the 2.7-percent pay increase for the troops, or a “whole-of-government response to the climate crisis.” Some of these initiatives are politically popular, but that’s not where lawmakers are porking up the budget. Spending on military personnel is actually down relative to FY 2021 (-$400 million, or -0.2 percent).

What’s up, then? Procurement (i.e., acquisition) of new ships, planes, and weapons for the military gets a major boost in the new defense budget — $15 billion, or 11.1 percent, more than the Biden budget request. Research and development spending, often on new ships, planes, and weapons that have yet to be built and procured, is also up a big $5.7 billion, or 5.1 percent, from the president’s budget request.

This extra spending will buy the Navy new ships, prevent the Navy from retiring ships that it wants to retire, and allow the service branches to purchase plenty of “new aircraft, combat vehicles, autonomous systems, missiles, and ammunition.” Much of the extra spending goes to so-called “unfunded priorities” requests of the military branches and combatant commands. My organization, National Taxpayers Union, calls them “wish lists.” In fact, they are more like stocking stuffers (tacked on to make the Christmas-time defense budget extra special for military officials and contractors) than essential presents under the tree.

Think lawmakers have fiscal responsibility at the Pentagon on their 2022 new year’s resolution list? Think again. Rep. Mike Rogers (R-Ala.), the top Republican on the House Armed Services Committee, is already warning that the “work is not finished” and that “combating [China and Russia] will continue to be our number one priority as we look ahead to FY23.” Unfortunately for the nation’s taxpayers, what “combating” these two nations often means is not spending smarter but spending more. Will we see an $800 billion military budget in 2022, for FY 2023? It’s not out of the question. It appears President Biden’s war budgets are going to look a lot like President Trump’s war budgets.