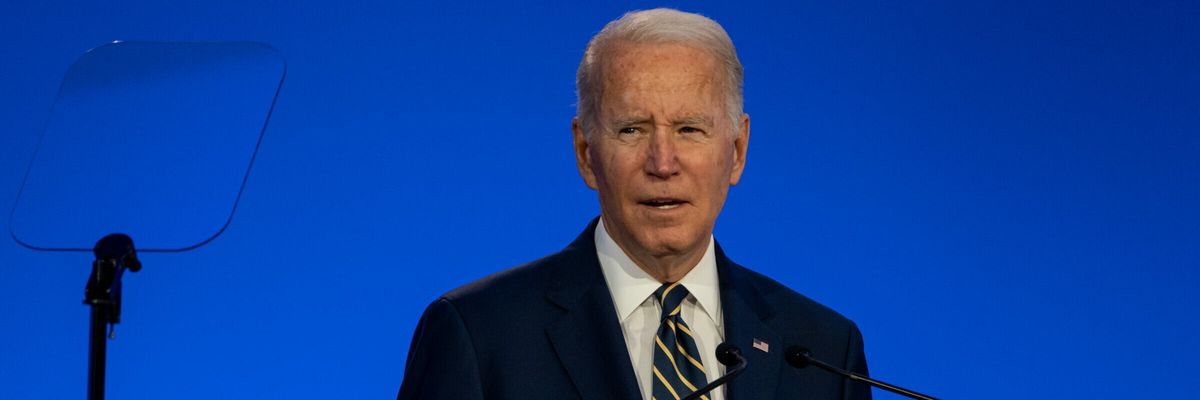

President Biden this week in Glasgow at the COP26 summit called climate change “the existential threat to human existence” and vowed that the United States would lead on the issue “by the power of our example.” But at the same time though, he seems to ignore the threat coming from the single largest American polluter — the U.S. military. The American armed forces are not just destroying the environment via its direct operations, but its very nature makes the military intrinsically dependent on burning tons of fossil fuels.

The U.S. Department of Defense is indeed the world’s single largest consumer of oil. In 2019, a report found that if the military was a country, it would be the 47th largest emitter of greenhouse gases.

According to Jeff Colgan, director of Brown University’s Climate Solutions Lab, militaries have been operating on a “no fuel, no victory” mindset. Fossil fuels, he says, have high energy density, often making it the only available fuel for most military operations, especially overseas where there is little to no infrastructure for green energy.

However, the military’s pollution isn’t limited to just burning fossil fuels. War has a localized impact like water pollution and other environmental damage. The U.S. military has a prolonged history of destroying ecosystems that stand in the way of war, with perhaps the most infamous example being the use of Agent Orange during the Vietnam War. More recently, the U.S. military has abandoned bases holding toxic waste in Afghanistan without properly cleaning them up, leaving behind so-called “burn pits,” where massive amounts of waste are burned releasing polluting and toxic elements into air.

So far there has been no plan to stop using them. A popular way of disposing of trash on overseas bases, around 3.5 million Americans were exposed to burn pits while serving, and they have caused serious health problems, such as cancer, for many American veterans, not to mention the negative impact on the local population.

Abandoned American bases can stoke political tensions even outside the traditional hotspots in the Middle East. For instance, Greenladers are worried about the thawing of hazardous waste from a Cold War-era base buried in the country’s vast ice sheet. The waste at that base covers 136 acres and includes an unknown volume of radioactive coolant. If left uncontained, the waste has potential to pollute the ocean, thereby threatening sea life and poisoning food supplies.

Many activists and experts also point out that the United States focuses on international rivalry rather than on the looming threat of climate change. Others are angry that the struggle against climate change is not funded as well as the military. “The amount of money spent on the military versus the amount of money spent on solving the climate crisis is hugely unjust,” Talia Woodin, a British environmental activist, told Responsible Statecraft.

Indeed, Biden’s budget for tackling climate change is just $36 billion while the House recently approved a budget for the Pentagon that is literally 20 times that. The president recently said that he wants $555 billion over ten years for climate and green energy measures — which is still far less than what the Pentagon will receive over that time and less than what the experts expect to be needed to combat the climate emergency. Estimates vary, but according to one study by Morgan Stanley, combating climate change by transitioning to net zero will require around $50 trillion.

Meaningfully “greening” our armed forces is proving challenging. The military has been attempting to wean itself off fossil fuels for some time — for instance, the Air Force is a major leader in green fuels. The Pentagon also often utilizes solar power and hybrid engines even in combat operations. But last year alone, the military was responsible for around 52 million tonnes in CO2 emissions. This is a relative improvement since the mid-2000s, when the output hovered above 60 million. But the U.S. military still emits more than the entire output of Sweden.

In 2020, the Pentagon reported that it replaced 44 percent of its vehicles with hybrid and electric cars. However, this does not apply to combat vehicles, ships, or jets. Michael Klare — a Five Colleges professor of Peace and World Security Studies at Hampshire College specializing on oil politics and national security — told Responsible Statecraft that “the U.S. military, in its stateside, peacetime operations, is going green, at a faster rate than most domestic institutions. The remaining problem is to convert combat vehicles — planes, ships, tanks, etc. — away from their current reliance on petroleum, as that is where the military remains a major source of CO2.”

What can Biden do to reduce the environmental harm caused by the military? Some, like Klare, would argue that more focus on greening combat operations is needed. Military projects in this sphere include the extensive solar panel use in Afghanistan. Klare is optimistic about the military's greening, saying that it’s “not a technical or financial problem, but one of leaders taking the necessary steps.”

Others are less optimistic about greening war. As Colgan said, “Modern military fighting depends […] on fossil fuels. It is possible in the distant future to move away from that, at the present that’s what military fighting involves.”

The Institute for Policy Studies recently warned against greenwashing the military. They point out that there is so far no viable “green” alternative to jet fuel, which constitutes the majority of the military’s energy use. IPS proposes cutting weapons manufacturing, closing down unnecessary bases, and ending American wars in order to place more limits on military pollution.

Meanwhile, Win Without War, a D.C.-based progressive foreign policy advocacy coalition, argues that “by massively scaling back the global military machine, the U.S. can cut emissions and devote resources to efforts that actually make people around the world more secure.” The group says that endless wars and the global U.S. military footprint are inherently carbon-intensive, adding that “just one percent of this year’s $740 billion military budget is enough to fund 128,879 green infrastructure jobs.”

To address the issue of the climate crisis beyond just cutting military emissions, experts argue, cooperation with great powers, especially China, is required. The Quincy Institute’s Anatol Lieven says that the United States needs to re-think its priorities: “spending on efforts to limit climate change and mitigate its effects should take precedence over military spending, especially on new, vast, and nonessential programs such as the upgrading of America’s nuclear forces, which are already much larger than nuclear deterrence requires.”