This summer we witnessed, with brutal clarity, the Beginning of the End: the end of Earth as we know it — a world of lush forests, bountiful croplands, livable cities, and survivable coastlines. In its place, we saw the early manifestations of a climate-damaged planet, with scorched forests, parched fields, scalding cities, and storm-wracked coastlines. In a desperate bid to prevent far worse, leaders from around the world will soon gather in Glasgow, Scotland, for a U.N. Climate Summit. You can count on one thing, though: all their plans will fall far short of what’s needed unless backed by the only strategy that can save the planet: a U.S.-China Climate Survival Alliance.

Of course, politicians, scientific groups, and environmental organizations will offer plans of every sort in Glasgow to reduce global carbon emissions and slow the process of planetary incineration. President Biden’s representatives will tout his promise to promote renewable energy and install electric-car-charging stations nationwide, while President Macron of France will offer his own ambitious proposals, as will many other leaders. However, no combination of these, even if carried out, would prove sufficient to prevent global disaster — not as long as China and the U.S. continue to prioritize trade competition and war preparations over planetary survival.

In the end, it’s not complicated. If the planet’s two “great” powers refuse to cooperate in a meaningful way in tackling the climate threat, we’re done for.

That harsh reality was made clear in September. The United Nations then issued a report on the likely impact of pledges already made by the nations that signed the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement (from which President Trump withdrew in 2017 and which the U.S. has only recently rejoined). According to the U.N.’s analysis, even if all 200 signatories were to abide by their pledges — and almost none have — global temperatures are likely to rise by 2.7 degrees Celsius (nearly 5 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels by century’s end. And that, in turn, most scientists agree, is a recipe for catastrophically irreversible changes to the planetary ecosphere, including the kind of sea level rise that will inundate most American coastal cities (and many others around the world) and the sort of heat, fire, and drought that will turn the American West into an uninhabitable wasteland.

Scientists generally agree that, to avert such catastrophic outcomes, global warming must not exceed, at worst, 2 degrees Celsius over pre-industrial levels — and preferably, no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius. Mind you, the planet has already warmed 1 degree Celsius and we’ve only recently seen just how much damage even that amount of added heat can produce. To limit warming to 2 degrees Celsius, by 2030, scientists believe, global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions would have to be reduced by 25% from 2018 levels; to limit it to 1.5 degrees, by 55%. Yet those emissions — driven by strong economic growth in China, India, and other rapidly industrializing nations — have actually been on an upward trajectory, rising on average by 1.8% per year between 2009 and 2019.

Several European countries, including Denmark, Norway, and the Netherlands, have launched heroic efforts to lower their emissions to reach that 1.5 degree target, setting an example for nations with far bigger economies. But however admirable, in the grand scheme of things, they just won’t matter enough to save the planet. Only the United States and China, by far the world’s top two carbon emitters, are in a position to do so.

It all boils down to this: to save human civilization, the U.S. and China must dramatically reduce their CO2 emissions, while working together to persuade other major carbon-emitting nations, beginning with fast-rising India, to follow suit. That would, of course, mean setting aside their current antagonisms, however important they may seem to U.S. and Chinese leaders today, and instead making climate survival their number one priority and policy objective. Otherwise, put simply, all is lost.

The U.S.-China carbon juggernaut

To fully grasp just how central China and the United States (the largest carbon polluter in history) are to the global climate-change equation, you have to grasp their present roles in both carbon consumption and CO2 emissions.

In 2020, according to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2021 (a widely respected source), China was the world’s top user of coal, the most carbon-intense of the three fossil fuels. That country was responsible for a staggering 54.3% of total world consumption; India came in second at 11.6%; and the U.S. third at 6.1%. When it came to petroleum consumption, the U.S. took first place with 19.9% of world usage and China came in second with 15.7%. The U.S. was also number one when it came to consumption of natural gas, followed by Russia and China.

Combine all three kinds and China and the U.S. were jointly responsible for 42% of total global fossil-fuel consumption in 2020. No other countries came even remotely close. Rising fast in the energy realm, India accounted for 6.2% of global fossil-fuel consumption and the European Union for 8.5%, which should give you some idea of the way the two countries dominate the global energy equation.

Not surprisingly, since they’re responsible for such a large share of fossil-fuel consumption every year and the combustion of those fuels is responsible for the overwhelming majority of global carbon emissions, China and the U.S. also account for a comparably large share of those discharges. According to BP, China was the world’s leading source of CO2 emissions in 2020, responsible for 30.7% of the global total, while the United States came in second with 13.8%. No other country even reached double digits and the European Union as a whole accounted for only 7.9%.

Put simply, the heating of this planet can’t be slowed down and eventually stopped if the U.S. and China don’t slash their carbon emissions drastically in the coming decades and invest massively — on a scale comparable to preparing for a world war — in alternative energy systems. We’re talking about trillions of dollars of future expenses. But there’s really no choice, not if we want to save our civilization.

The mastodon in the room

Any strategy to substantially reduce global CO2 emissions and keep global warming from exceeding 2 degrees (let alone 1.5 degrees) Celsius above pre-industrial levels must confront the largest obstacle to success around: China’s continuing reliance on coal to provide the lion’s share of its energy supply. According to BP, in 2020, China obtained 57% of its primary energy needs from coal. No other country comes close to that. If China was responsible for 26% of total world energy consumption that year, then its coal combustion alone constituted 15% of global energy usage — a greater share than Europe’s from all energy sources combined.

If China phases out its coal plants in this decade and other countries followed through on their Paris commitments, meeting that target of 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius and avoiding a climate Armageddon would at least be possible. But that’s not the way China’s headed. Not faintly. According to some reports, that country is actually expected to boost (yes, boost!) its coal consumption in this decade by adding 88 gigawatts of coal-fired power capacity. (A large, modern coal-fired plant can generate about 1 gigawatt of electricity at a time.) Worse yet, its officials are mulling over plans to sooner or later build another 159 gigawatts worth. Because coal is the most carbon-intensive of the fossil fuels, to construct and operate so many new coal-powered plants will add monstrously to China’s CO2 emissions, making a sharp reduction in global emissions impossible.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has indeed spoken of building an “ecological civilization” and has also promised to halt the rise in China’s carbon emissions by 2030. For a time, it appeared that he was even prepared to take stern measures to halt the growth of China’s coal consumption. He did, in fact, pledge that his country would reach peak oil consumption by 2025 and halt the financing of the construction of coal plants abroad as part of its globalizing “Belt and Road Initiative,” a major shift in policy. But it seems that his government has otherwise turned a blind eye to efforts by provincial governments and powerful state-owned energy firms to rush the construction of new coal plants at home.

Western analysts believe that Chinese leaders are desperate to propel economic expansion in the wake of the Covid pandemic. Offering cheap energy from coal is one obvious way of facilitating investment in new infrastructure projects, a standard tactic for boosting growth. Some analysts also suspect that Beijing has allowed coal production to increase in response to U.S. trade sanctions and other expressions of Washington’s hostility. “The recent U.S.-China trade war has further heightened Chinese concerns about energy security, given that the country imports roughly 70% of its oil needs and 40% of its gas requirements,” Daniel Gardner of Princeton’s High Meadow Environmental Group pointed out in the Los Angeles Times, adding, “Coal — abundant and relatively inexpensive — seems to many a reliable, tried-and-true energy source.”

Why a U.S.-China climate survival alliance is essential

Recently, during a meeting with top officials in Tianjin, President Biden’s global climate envoy, former Secretary of State John Kerry, chided the Chinese for their addiction to coal. “Adding some 200-plus gigawatts of coal over the last five years, and now another 200 or so coming online in the planning stage, if it went to fruition would actually undo the ability of the rest of the world to achieve a limit of 1.5 degrees [Celsius],” he reportedly said to them during their interchange.

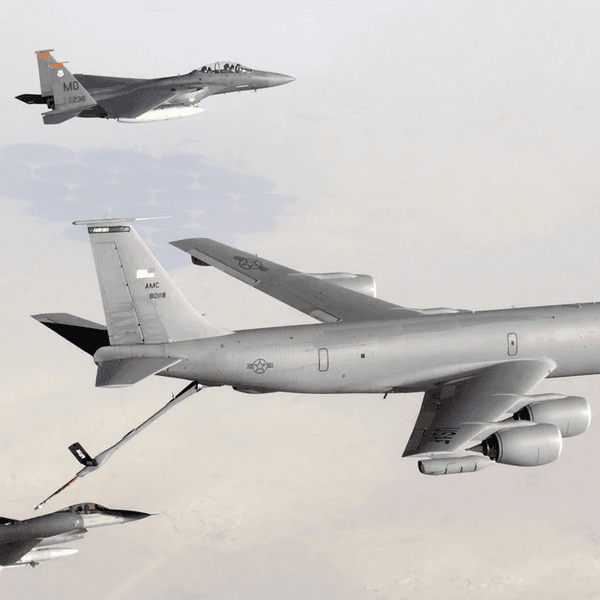

There was, however, no way Chinese leaders were going to respond positively to his entreaties, given the growing hostility between the U.S. and China. Even more than during the final Trump years, Washington under President Biden has voiced support for Taiwan — considered a renegade province by Beijing — while seeking to encircle China with an ever-more-militarized network of anti-Chinese alliances. These include the newly formed “AUKUS” (Australia, the United Kingdom, and the U.S.) pact that also involved the ominous promise to sell American nuclear-powered submarines to the Australians. Chinese leaders have responded angrily that any progress on climate change must await improvement in what they consider more critical aspects of their relationship with America.

“China-U.S. cooperation on climate change cannot be divorced from the overall situation of China-U.S. relations,” Foreign Minister Wang Yi told Kerry during his September visit to China. “The U.S. side wants the climate change cooperation to be an ‘oasis’ of China-U.S. relations. However, if the oasis is all surrounded by deserts, then sooner or later, the ‘oasis’ will be desertified.”

In theory, the two countries could pursue the goal of radical decarbonization on their own — each independently spending the necessary trillions of dollars on domestic energy transformation. It is, however, essentially impossible to imagine such an outcome in today’s world of intensifying military and economic competition. In March, for instance, China announced a 6.8% increase in military spending for 2021, raising the official budget of the People’s Liberation Army to $209 billion. (Many analysts believe the actual figure is much higher.) Similarly, on Sept. 23rd, the U.S. House of Representatives authorized defense spending of $740 billion for Fiscal Year 2022, $24 billion more than the staggering sum requested by the Biden administration. Both countries are also moving to “decouple” their critical supply lines, while investing vast amounts in the race to dominate technologies like artificial intelligence, robotics, and microelectronics assumed to be essential to future success, whether in trade wars or actual ones. Neither is planning to invest anything faintly comparable in efforts to slow the pace of global warming and so save the planet.

Only when China and the United States elevate the threat of climate change above their geopolitical rivalry will it be possible to envision action on a sufficient scale to avert the future incineration of this planet and the collapse of human civilization. This should hardly be an impossible political or intellectual stretch. On January 27th, in an Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis, President Biden did, in fact, decree that “climate considerations shall be an essential element of United States foreign policy and national security.” That same day, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin issued a companion statement, saying that his “Department will immediately take appropriate policy actions to prioritize climate change considerations in our activities and risk assessments, to mitigate this driver of insecurity.” (At the moment, however, the thought that Republicans in Congress would support such positions, no less fund them, is beyond imagining.)

In any case, such comments have already been overshadowed by the Biden administration’s fixation on dominating China globally, as have any comparable impulses on the part of the Chinese leadership. Still, the understanding is there: climate change poses an overwhelming existential threat to both American and Chinese “security,” a reality that will only grow fiercer as greenhouse gases continue to pour into our atmosphere. To defend their respective homelands not against each other but against nature, both sides will increasingly be compelled to devote ever more funds and resources to flood protection, disaster relief, fire-fighting, seawall construction, infrastructure replacement, population resettlement, and other staggeringly expensive, climate-related undertakings. At some point, such costs will far exceed the amounts needed to fight a war between us.

Once this reckoning sinks in, perhaps U.S. and Chinese officials will begin forging an alliance aimed at defending their own countries and the world against the coming ravages of climate change. If John Kerry were to return to China and tell its leadership, “We are phasing out all our coal plants, working to eliminate our reliance on petroleum, and are prepared to negotiate a mutual reduction in Pacific naval and missile forces,” then he could also say to his Chinese counterparts, “You need to start phasing out your coal use now — and here’s how we think you can do it.”

Once such an agreement was achieved, Presidents Biden and Xi could turn to Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India, and say, “You must follow in our footsteps and eliminate your dependence on fossil fuels.” And then, the three together could tell the leaders of every other nation: “Do as we’re doing, and we’ll support you. Oppose us, and you’ll be cut off from the world economy and perish.”

That’s how to save this planet from a climate Armageddon. There really is no other way.

This article has been republished with permission from TomDispatch.

(Shana Marshall)

(Shana Marshall)