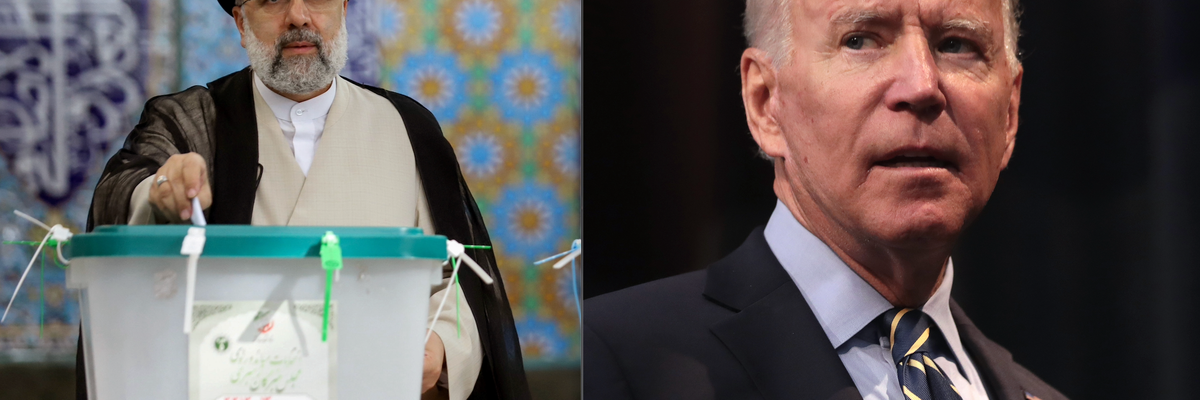

Deep into the Biden administration’s first year, the United States and Iran have failed to restore the Iran nuclear deal and negotiations have yet to resume after Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi was inaugurated in early August. Far from desperate for a deal, as many Washington commentators portrayed, Iran is content to bide its time and believes it is in a strong position to either restore the agreement on its terms, pursue a new bargain, or escalate tensions with the United States further. Whether the JCPOA can still be salvaged remains to be seen, but understanding some of the reasons why the United States and Iran have not sealed the deal could help policymakers bridge the gaps that remain.

A slow start and mixed signals

Joe Biden took office on January 20 amid unprecedented domestic upheaval, so it was perhaps not a surprise that the Biden administration did not make restoring the Iran nuclear deal — a prospect deeply, and irrationally, opposed by virtually all Republicans — a Day One priority. But given the narrow window to restore the deal ahead of Iran’s June elections, delay and ambiguity worked against the administration’s goals.

Then-Iranian President Hassan Rouhani met Biden’s inauguration with a clear statement that Iran would respond reciprocally to any U.S. move. By contrast, instead of a clear signal that the United States was intent on returning to the deal, early statements from the Biden administration eroded confidence and political capital in Tehran for a quick and simple return.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken and other officials, in nomination hearings that were closely watched in Tehran, implied that Iran must move first before the United States would return to the agreement. In so doing, they underscored that things had changed since 2015, that they were interested in a “longer and stronger” agreement while downplaying fast movement toward the JCPOA. Such rhetoric may have played well in confirmation hearings, but sent mixed signals to Tehran.

Had the Biden administration complemented this rhetoric with clear actions — such as revoking President Trump’s order withdrawing the United States from the deal, authorizing the secretary of state to waive JCPOA-related sanctions or concrete steps to ease sanctions in light of the COVID-19 pandemic — much confusion could have been avoided.

But the administration’s first moves on Iran in mid-February were rather limited, simply acknowledging that the prior administration’s bizarre U.N. snapback attempt had failed and enabling Iranian diplomats in New York greater mobility. Without a major step, Iran bristled at Washington’s rhetoric, indicating that there was “no chance” to renegotiate the agreement while insisting that Washington needed to move to lift sanctions in order for Iran to return to compliance.

To mark the Persian New Year in March, Supreme Leader Khamenei weighed in, underscoring that U.S. sanctions had failed and directly rebutting arguments from U.S. officials. If the Biden administration were to continue Trump’s maximum pressure campaign, he said, it too will “get lost and be defeated.” Regarding changes since 2015, Khamenei declared, “Yes! The situation has changed in comparison to 2015 but it hasn’t changed in America’s favor, but to our favor…Iran is much stronger today than in 2015. So, if the JCPOA is to be changed, it must be to Iran’s benefit. We neutralized the effect of sanctions.” He warned that Iran had made a mistake by rushing into the JCPOA in 2015, that the United States had failed to abide by its sanctions commitments, and that Iran would not make the same mistake twice.

The Biden administration’s Iran envoy Robert Malley — who was brought on in late January — took key steps to clarify the U.S. position beginning in March. He repudiated the maximum pressure policy and declared that Washington wanted to revive the JCPOA in a synchronized manner and that the United States knows what steps it has to take to relieve sanctions. As he told PBS, “we will have to go through that painstaking work of looking at those [Trump-era] sanctions and seeing what we have to do so that Iran enjoys the benefits that it was supposed to enjoy under the deal.” Unsurprisingly, negotiations toward a JCPOA revival resumed in early April, once the Biden team had taken a more clear position. However, precious months had been lost.

Sabotage

Shortly after Malley’s PBS interview, Israel — then under the leadership of Benjamin Netanyahu — expressed displeasure. Senior Israeli officials reportedly indicated that Malley’s remarks “‘raised eyebrows’ at the highest echelons in Israel.”

Iran was still seething from a withering covert campaign at the end of 2020. The U.S. assassination of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani in early January was followed by purported Israeli operations including an explosion that destroyed Iran’s advanced centrifuge production facility at Natanz in July and the assassination of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh — the grandfather of Iran’s nuclear program — on the eve of President Biden assuming office. After that attack, Iran’s parliament passed a bill mandating rapid nuclear expansion and limiting enhanced inspections established by the nuclear deal. As a senior Iranian official told the International Crisis Group in December, “The West seems unaware of how much we have suffered, how humiliated we feel after the assassinations of Soleimani and Fakhrizadeh, how angry we feel about so many covert operations, how painful our strategic patience has been.”

The JCPOA Joint Commission hailed progress amid a constructive environment after the first week of multilateral negotiations on April 9. Two days later, the Israelis, presumably, triggered an explosion at the Natanz enrichment site, causing a blackout and knocking many of Iran’s first generation centrifuges offline. Breaking with precedent, Israel had reportedly given the United States less than two hours’ notice before proceeding with the covert operation, which left no time for the Biden administration to caution against or convince Israel to call off the attack. If that wasn’t enough, a separate, lesser-known attack targeting one of Iran’s centrifuge manufacturing facilities in June appears to have destroyed an IAEA monitoring camera and damaged another installed at the facility, causing complications for the agency’s monitoring efforts.

Under a time-crunch to conclude negotiations, Israel had demonstrated yet again its capabilities of striking deep inside Iran at its most secure facilities. The Natanz explosion immediately triggered an announcement by Iran of uranium enrichment to a level closer to "weapons grade" that Iran had not previously attempted. Khamenei would later admonish the Rouhani government in July, accusing it of trusting the West and inviting aggression. “They [the West] will try to hit us everywhere they can and if they don’t hit us in some place, it’s because they can’t,” Khamenei said.

The path forward

In July, after Raisi’s election, the Foreign Ministry presented a report to parliament detailing just how far negotiations had come. The report shows that many Trump-era sanctions intended to sabotage the JCPOA were allegedly on the table. It urged the Raisi administration to finish the job, while warning that a “maximalist approach will only lead to endless negotiations” and that there is no perfect deal to be had.

Raisi will soon test that logic. At minimum, he is taking the Supreme Leader’s admonitions not to rush into an agreement to heart, as Raisi has yet to give indication that a resumption of talks is close at hand.

It is important for the Biden administration not to fall into the trap that Iran hawks have set by adopting a more rigid posture to negotiations. Since its slow start, the Biden administration has been clear that its preferred approach to negotiations is through diplomacy and that it is willing to lift sanctions to restore compliance with the agreement. This flexibility needs to continue if the path to the JCPOA, or any diplomatic agreement, is to be sustained.

Further escalatory steps — such as a censure of Iran at the IAEA Board of Governors, covert sabotage of Iranian nuclear facilities, or efforts to snap back sanctions — will only force Iran to double down. As Khamenei’s statements have demonstrated, he believes Iran holds many cards while Washington has expended many of its own in a feckless pressure campaign. Moreover, the United States should avoid rigid demands that go above and beyond what is required of a compliance-for-compliance return to the nuclear deal. Insisting on Iran agreeing to further negotiations, when it is the United States that violated the JCPOA first, may project a tough negotiating posture but reinforces those in Iran who oppose the JCPOA or are pushing for steps that Washington cannot take, like full proof guarantees that the United States never violates the JCPOA under a future administration.

Moreover, while the Biden administration has tried to restore an agreement, it could ease sanctions up front as a goodwill gesture. Iran has made clear that it viewed a cave to maximum pressure as a greater threat than the sanctions themselves, as it would only invite further U.S. pressure. However, the Biden administration has sought to negotiate the agreement, and secure additional commitments on negotiations, while keeping Trump’s sanctions pressure largely intact.

This has reinforced Iranian skepticism toward U.S. intentions on the JCPOA, helping to scuttle progress earlier in the year. However, there are steps the Biden team could take to deliver concrete humanitarian assistance or relief, independent of the JCPOA, that would dispel the Supreme Leader’s false claims of equivalence between Trump and Biden and make clear that offers of sanctions relief and diplomacy are sincere. This would require political courage, but there is little to lose and goodwill to gain.

The path ahead will not be easy. But we know that max pressure has failed and that the United States and Iran might not be able to avoid a disastrous war if Iran chooses its own form of maximum pressure. The JCPOA might still be salvaged, but maintaining diplomatic flexibility is a must.