Today in our series 9/11 at 20: A week of reflection, we hear from Jim Lobe, Senior Advisor and contributing editor at Responsible Statecraft.

When excerpts of the document first appeared in the New York Times in March 1992, it created quite a stir. One influential Democrat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee was appalled by its ambition, denouncing it as “literally a ‘Pax Americana.’ A global security system where threats to stability are suppressed or destroyed by U.S. military power.”

Indeed, the draft Defense Planning Guidance, or DPG, which set forth the underlying elements of U.S. grand strategy through the end of the century, was stunning in its vision for permanent U.S. military dominance of virtually all of Eurasia — to be achieved by “deterring potential competitors from even aspiring to a larger regional or global role” and by preempting, using whatever means necessary, states believed to be developing weapons of mass destruction.

Written under the direction of then-Undersecretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz and his deputy, I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, it foretold a world in which U.S. military intervention would become a “constant fixture” of the geopolitical landscape, and Washington — not the United Nations, which went unmentioned despite the Security Council’s role in authorizing the first Gulf war the year before — would act as the ultimate guarantor of international peace and security.

The “dominant consideration,” it said, “…requires that we endeavor to prevent any hostile power from dominating a region whose resources would, under consolidated control, be sufficient to generate global power. …In the Middle East and Southwest Asia, our overall objective is to remain the predominant outside power in the region…”

“While the U.S. cannot become the world’s ‘policeman’ by assuming responsibility for righting every wrong,” the draft declared, “we will retain pre-eminent responsibility for addressing selectively those wrongs which threaten not only our interests, but those of our allies or friends, or which could seriously unsettle international relations.”

The leak, apparently by someone in the Pentagon who thought that such a clearly imperial vision should be subject to public debate, sparked an uproar. At the insistence of then-national security adviser Brent Scowcroft and Secretary of State James Baker, the DPG was substantially toned down when it was released a month later.

From the DPG to a ‘new American century’

But the draft’s imperial vision didn’t die. It clearly retained a central place in the hearts of minds of its two directors and their boss, then-Defense Secretary Dick Cheney, as well as a kind of Machtpolitik coalition of Israel-centered neoconservatives and aggressive nationalists that had first coalesced in the mid-1970s when Cheney, then-President Ford’s chief of staff, and his Pentagon chief, Donald Rumsfeld, worked successfully to derail Henry Kissinger’s efforts to promote détente with the Soviet Union. That coalition was later joined during the Carter administration by ultra-Zionist leaders of the Christian and Catholic Right, such as Jerry Falwell and William Bennett. Combined, this alliance constituted a formidable political force that helped propel Ronald Reagan to the presidency and laid the groundwork for George W. Bush’s election 20 years later.

The draft DPG’s basic ideas and the Machtpolitik coalition behind them took institutional form in 1997 with the creation of the Project for the New American Century. Founded by neoconservatives Robert Kagan and William Kristol, co-authors of an influential article the previous year that promoted U.S. “benevolent global hegemony,” PNAC’s “Statement of Principles” called for “a Reaganite policy of military strength and moral clarity” whose first requirement — despite the fact that the Pentagon budget at the time was greater than the military budgets of the eight biggest foreign powers combined — should be to “increase defense spending significantly.”

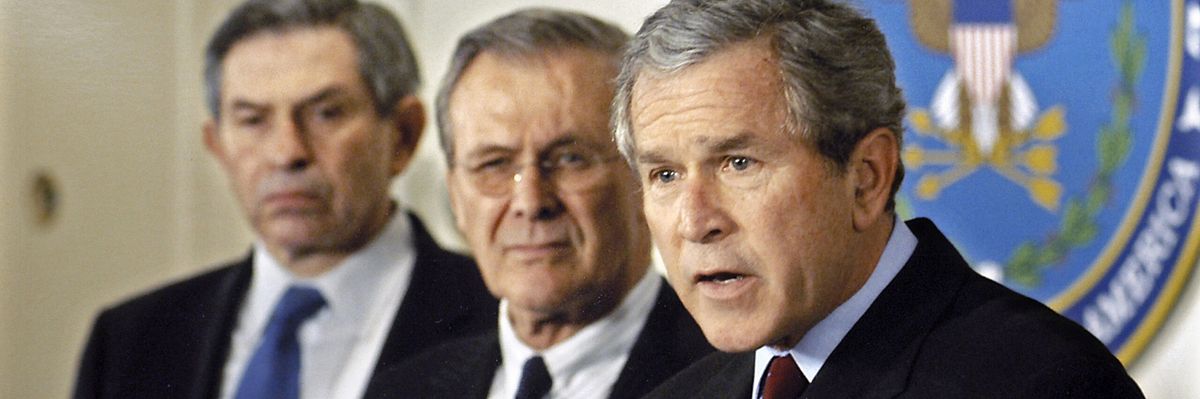

While PNAC’s creation garnered virtually no public attention, it should have, given the names of the Charter’s 25 signatories. Four years later, a half dozen of them would be installed in top national security posts in the Bush administration, including Cheney (vice president); Rumsfeld (secretary of defense); Libby (Cheney’s chief of staff and national security adviser), Wolfowitz (deputy defense secretary), Zalmay Khalilzad (senior director on the National Security Council) and Peter Rodman (assistant secretary of defense for International Security Affairs).

PNAC, whose publications generally represented the consensus positions of the Machtpolikers’ three factions, wasted little time in making its more specific regional views known, particularly on Middle East policy. In 1998, it published two letters urging the Clinton administration and Congress to, among other things, “be prepared to use (military) force …to help remove (Iraqi President) Saddam (Hussein) from power.” In addition to Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, and Rodman, the letters’ signers included Elliott Abrams, who would become the senior Mideast aide on Bush’s National Security Council; John Bolton, who would take a top State Department job; and, perhaps most important, Richard Perle, a master Beltway operator and hardline neoconservative, whom Rumsfeld chose as chairman of the Defense Policy Board.

In 1996, Perle had worked with proteges Douglas Feith and David Wurmser on a 1996 memo for incoming Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu that called for an aggressive effort to oust Saddam Hussein and destabilize Syria as part of strategy to free Israel from being forced to give up land to the Palestinians under the Oslo Accords. With Perle’s assistance five years later, Feith, a proponent of Greater Israel, would claim the number three role at the Pentagon, while Wurmser, who, in the meantime, published an entire book making the case for overthrowing Saddam, was hired by Cheney as his top Middle East adviser.

Updating the DPG

In September 2000, PNAC published a 90-page report entitled “Rebuilding America’s Defenses” based in major part on the 1992 draft DPG which it praised as a “blueprint for maintaining U.S. preeminence, precluding the rise of a great power rival, and shaping the international security order in line with American principles and interests.”

Among other recommendations to ensure the duration of that preeminence, the “Rebuilding” report called for “a larger U.S. security perimeter” beyond Western Europe and Northeast Asia by “shifting permanently-based forces to Southeast Europe and Southeast Asia…,” “establish[ing] a network of ‘deployment bases’ or ‘forward operating bases’ to increase the reach of current and future forces” — what Rumsfeld would later refer to as “lily pads” — and by “facing up to the realities of multiple constabulary missions that will require a permanent allocation of U.S. forces,” or what the DPG referred to as “a constant fixture” of the geopolitical landscape.

The report also urged creating a “U.S. Space Forces with the mission of space control” and enhancing its military presence in Southeast Asia” to “cope with the rise of China to great-power status.”

Predictably, the PNAC report also called for major annual increases in defense spending but noted ruefully that the money and political will needed to achieve “tomorrow’s military dominance” was likely to take a long time to muster “absent some catastrophic event — like a new Pearl Harbor.”

The DPG realized

Almost exactly one year later, al-Qaida’s attack on New York’s World Trade Center and the Pentagon constituted precisely such an event, and PNAC and its associates — now embedded in top national-security posts throughout the new Bush administration — were prepared to take full advantage, harnessing what came to be called “the Global War on Terrorism” to their own imperial dreams of global U.S. military domination, including “regime change” in Middle Eastern states deemed hostile to the United States and Israel. Significantly, neither the draft DPG nor the “Rebuilding” report mentioned the threat of terrorism by non-state actors.

Indeed, nine days after 9/11, PNAC published a new letter that, in addition to urging al-Qaida’s destruction, “necessary military action in Afghanistan,” and “a large increase in defense spending,” also insisted on a “determined effort to remove Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq …even if evidence does not link Iraq directly to the [9/11] attack.” The letter also cited Lebanon’s Hezbollah, Iran, and Syria as future candidates for U.S. military action if they failed to bow to U.S. demands.

As U.S. forces allied with Afghanistan’s Northern Alliance ousted the Taliban and chased al-Qaida remnants into Pakistan, and the foreign policy elite and historians debated whether the U.S. “empire” had exceeded those of Britain or Rome in power and greatness, Bush administration officials began preparing to invade Iraq. Rumsfeld himself was telling aides to come up with plans to strike Iraq while Perle was on television claiming that Saddam was behind the 9/11 attacks within hours of the disintegration of the Twin Towers. In the weeks that followed, Pentagon and State Department officials were dispatched around the globe to effectively realize the DPG’s and PNAC’s imperial ambitions under the guise of counter-terrorism and fighting Islamist extremism.

Promises or the provision of new or upgraded aid in the forms of military training, weapons, joint exercises, intelligence support, forgiveness for gross human rights abuse were offered to dozens of countries in exchange for establishing, expanding, or gaining access to military bases not only in the Gulf Arab states and Afghanistan’s and Iraq’s closest neighbors (with the exception of Iran), but also in strategically located former Soviet states in the Caucasus and the heart of Central Asia on the very doorsteps of possible future “competitors” Russia and China. They offered virtually anything to get boots and spooks in the door.

In Southeast Asia, Washington quickly dispatched hundreds of special operations forces to Mindanao in the Philippines — marking the first major presence of uniformed U.S. military since Manila closed its giant Subic Naval Base and Clark Air Base in 1993 — to help fight a regional insurgency associated with al-Qaeda. The chief of the U.S. Pacific Command visited Hanoi to discuss counter-terrorism cooperation but mostly to press for “more participation by Vietnam in …regional military activities,” including visitation rights at the deep-water port of Cam Ranh Bay for U.S. Navy vessels.

A new base agreement was reached with Djibouti in the Horn of Africa, while, on the opposite of the Red Sea, Cheney himself concluded an accord in March 2002 on a trip to Sana’a to send some 100 military advisers to Yemen. Special forces were also sent to Georgia to help it deal with a regional insurgency.

All this activity amounted to what some critics correctly described as "the most significant expansion of U.S. global military presence since the end of the cold war,” precisely what the vision set forth by the draft DPG 10 years before. With “multiple constabulary missions,” and “new or upgraded deployment bases” or “forward operating bases” recommended by the 2000 “Rebuilding” report, the U.S. military was indeed fast becoming the “constant feature” of the global geopolitical landscape that the draft DPG, which was more or less codified in Bush’s 2002 “National Security Strategy,” called for 10 years before. And Congress appropriated a whopping 24 percent boost in the defense budget between fiscal 2002 and 2004.

Indeed, this is what the post-9/11 “Pax Americana” to which that Democratic senator — Joseph R. Biden — so strongly objected at the time looked like.

“It won’t work,” Biden warned then. “You can be the world superpower and still be unable to maintain peace throughout the world.” In fact, he may have added, you may only make things worse.