If the U.S. government was caught up short by the dramatic denouement of its 20-year war in Afghanistan, viewers of the three major networks must have been taken entirely by surprise.

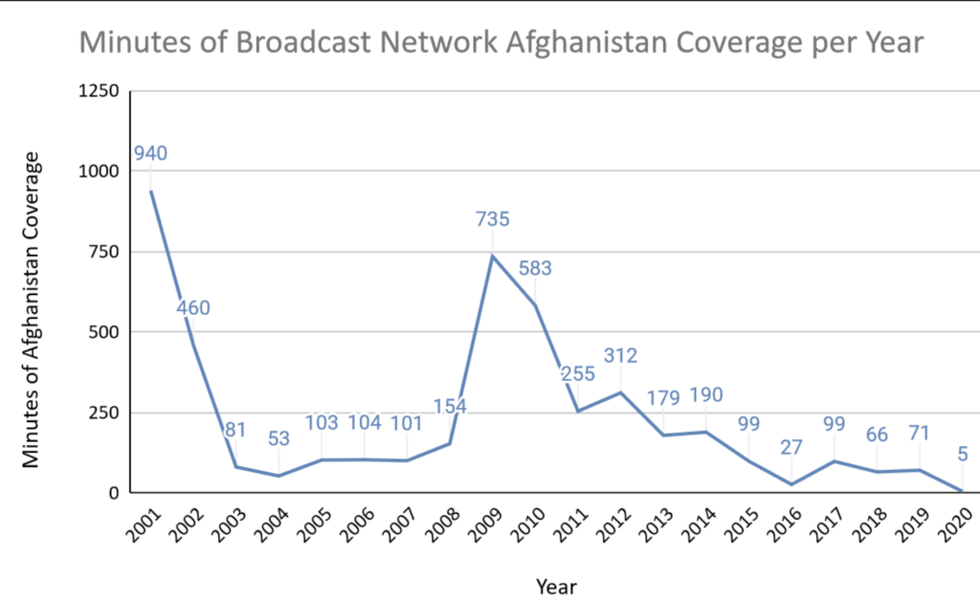

Out of a combined 14,000-plus minutes of the national evening news broadcast on CBS, ABC, and NBC last year, a grand total of five minutes were devoted to Afghanistan, according to Andrew Tyndall, editor of the authoritative Tyndall Report, which has monitored and coded the networks’ nightly news each weekday since 1988.

Those five minutes, which covered the February 2020 Doha agreement between the United States and the Taliban, marked a 19-year low for Afghanistan coverage on the three networks’ newscasts. They compared to a high of 940 minutes the networks devoted to Afghanistan in 2001, all of it following 9/11 and the subsequent U.S. intervention, as shown below.

While the pathetic amount of coverage of the conflict last year can be partially explained by the virtually total dominance of the news agenda by the COVID-19 pandemic, the three networks devoted a total of only 362 minutes to Afghanistan in the preceding five years, or just two hours of coverage per network, or an average of only 24 minutes per network per year.

“The network nightly newscasts have not been on a war footing in their coverage of Afghanistan since 2014,” Tyndall wrote on his blog Thursday, referring to the last year of the surge of troops initiated by Obama in his first term). “For the last seven years they have treated the role of the military there as an afterthought, essentially a routine exercise in training and support, generating little excitement, no noticeable jeopardy and few headlines.”

Indeed, as much as the networks and other mainstream media are currently focused on the fate of Afghans who worked with the U.S. and allied forces and may now be trying to flee the country, very little of the network coverage over the past 20 years addressed the plight of Afghan soldiers and civilians compared to that accorded to U.S. soldiers. In an interview with Responsible Statecraft, Tyndall estimated that 95 percent of network coverage of the fighting itself after 2002 was devoted to the U.S. role.

While the cable news networks often receive more attention, and more Americans use the internet to seek information about world events, the three evening network news shows collectively remain the single most important source of international news in the United States.

On weekday evenings, an average of about 20 million U.S. households tune in to national news on CBS, ABC, or NBC — roughly four times the number of households who rely on the major cable stations — Fox News, MSNBC, and CNN —for their news (as opposed to commentary) during prime time. Roughly two million more people are estimated to watch the network news via the internet, according to Tyndall.

Moreover, what appears on the national networks often contributes heavily to the overall news agenda for other U.S. media organizations. “Because network news shows are the most mainstream of the mainstream media,” Tyndall noted, “they can be used as a proxy for the news judgment of mainstream media more generally.”

Except for the 1991 Gulf War, the post-9/11 Afghan and Iraq invasions and occupations, followed by the George W. Bush's "Surge" of troops in Iraq in 2007, and Obama’s "Surge" in Afghanistan in his first term, foreign news has generally been in decline as the networks, as well as newspapers (many of which have folded due to sharp declines in advertising revenue), have closed bureaus to cut costs. In 2018, network coverage from overseas fell to the lowest point since at least 1988 (1,092 minutes out of a total of 14,354 minutes of newscasts). 2019 saw a slight uptick, but then, overwhelmed by COVID-related news, the networks hit rock bottom in news from abroad at 720 minutes -- or five percent of all evening network news coverage --in 2020 of which that five minutes of Afghanistan coverage constituted 0.7 percent.

In that respect, the decline in coverage of Afghanistan tracked a much broader trend of network and mainstream media coverage of — or disinterest in— the world outside the United States.

According to Tyndall, network news coverage of Afghanistan has gone through four phases. The first, when coverage was heaviest, was the immediate aftermath of 9/11 and the subsequent U.S. and allied invasion. “Phase Two, stretching from 2003 through 2008,” Tyndall wrote on his blog, “saw Afghanistan presented as a sideshow, overwhelmed by the larger and deadlier invasion of Iraq.” The third phase covered Obama’s surge (to a high of 100,000 U.S. troops in-country) from 2009 to 2014, followed by the fourth phase when the networks withdrew its coverage as the Pentagon drew down the U.S. military presence.

The ebb and flow of the coverage over the 20 years clearly corresponded to the ebb and flow of the U.S. troop presence, a fact that reflects how sharply focused were the networks on the role of the U.S. military in the fighting. That virtually exclusive focus inevitably affected the ability of the networks — and their viewers — to understand the domestic – that is, Afghan — dynamics of the conflict. Dynamics such as the massive corruption and consequent hollowness of the state apparatus established and supported by Washington, the human rights abuses committed by Afghan security forces and allied militias, and the sources of the Taliban’s political support, among other factors that ultimately proved decisive in the events of the past few weeks.

These issues weren’t completely ignored by the networks, according to Tyndall who noted that they ran occasional “sidebars” about internal Afghani politics, culture, education, women’s rights, and the drug trade, but the time devoted to these stories constituted a fraction of that dedicated to the violence and war, particularly as it involved U.S. ground forces.

When ground forces were withdrawn, the networks lost interest, permitting the Pentagon to conduct an air war that drew little notice (much as it has done elsewhere). “For the American networks, ‘war’ means troops on the ground in harm’s way, not use of lethal force remotely by the Pentagon,” Tyndall told Responsible Statecraft.

Tyndall noted ironically that the event on which the meager five minutes of network attention were focused on Afghanistan last year — the Doha agreement — actually did offer a viewers a hint of what was to come, although the paucity of even that coverage still made it difficult to see the full implications. “If the Doha talks had been responsibly covered,” he said, “people would’ve understood that the powers that be in the U.S. believed that the leading political actor in Afghanistan was the Taliban, not the government.”

Data on graph provided by Andrew Tyndall of The Tyndall Report