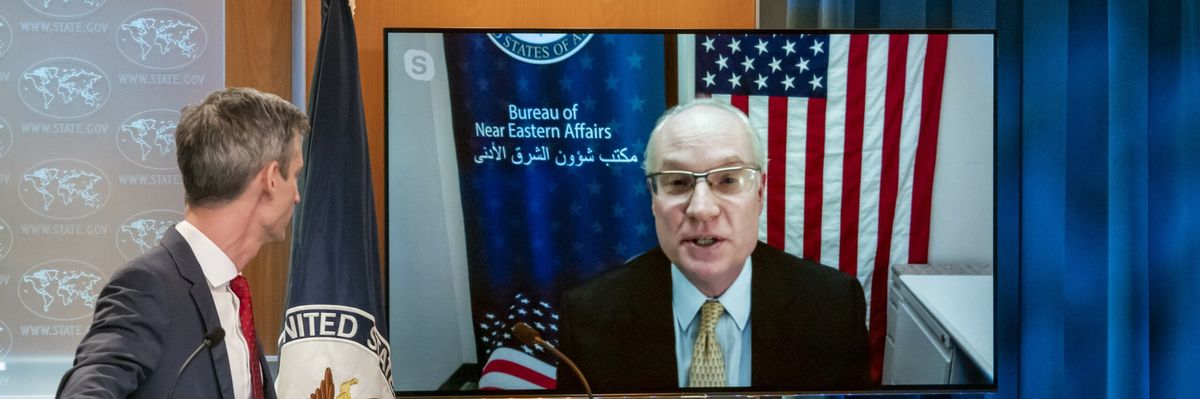

U.S. Special Envoy for Yemen Tim Lenderking will testify before both houses of Congress today, addressing the House Foreign Affairs Committee first, followed by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Members of both panels have expressed consternation at the lack of progress in U.S. efforts to address the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Yemen, and this frustration may come through in these hearings.

Pressure has grown from activists, celebrities, and members of Congress for the Biden administration to demand that Saudi Arabia lift the blockade on Yemen that is contributing to conditions of severe food insecurity faced by 16 million people and the specter of death for 400,000 children under age five. Yet the State Department recently contested the use of the word “blockade,” asserting that food is entering Yemen’s primary port at Houthi-controlled Hodeida. The State Department acknowledged that fuel import restrictions are alarming, but framed the Hadi government as responsible for imposing restrictions, rather than the Saudi navy, which has allowed only four fuel ships to dock since January 3.

Members of Congress should press Lenderking on these points, specifically why the State Department appears to be ignoring statements by the World Food Program, which cites the blockade as the single most important humanitarian concern for Yemen, as well as by the UN Human Rights Council’s Group of Eminent Experts, which concluded that the Saudi blockade amounts to a war crime.

They should also ask for clarification about why the U.S. government blames the Hadi government for the restrictions and ignores Saudi Arabia’s responsibility. The Hadi government lacks the on-the-ground capability to enforce its own edicts, while the Saudi government selects which of Hadi’s preferences align with its own agenda. In this case, working to prevent the Houthis from acquiring fuel revenues that the Saudis know will help fund their war effort lines up with the Hadi government’s desire to maintain the facade of its own control over Yemen. In addition, Lenderking needs to explain why Washington is tacitly supporting the starvation of Yemen by not pressuring Saudi Arabia to lift the blockade.

Lenderking will probably try to shift the hearing’s focus to the looming humanitarian catastrophe in the city of Marib. A hundred miles east of the capital of Sanaa, the city has offered refuge for over a million internally displaced people (IDPs) who have fled violence in general and the Houthis in particular. The Houthis have tried to take the city for over a year, given its strategic importance to the Hadi government and the Saudi military campaign, as well as the oil and gas infrastructure located there. Both Lenderking and the Saudis have stressed the need to protect Marib from the Houthi advance, and the prospect of a Houthi takeover of the city is grim, as civilians would either come under attack or be forced to flee into the surrounding desert of the Rubʿ al-Khali, or Empty Quarter, some of the world’s least hospitable terrain.

If Saudi Arabia and Lenderking are concerned about Marib, they should propose a means of providing assistance to the population there, such as a UN-led international effort to help move IDPs away from the front lines to other parts of Yemen.

Instead, Lenderking and the Saudis argue that the blockade should only be lifted if the Houthis agree to a ceasefire in Marib. This argument is problematic because it operates under a logic that considers the ongoing starvation of Yemenis to be an acceptable bargaining chip. Moreover, Lenderking and the Saudis know that their various ceasefire proposals are likely to be rejected by the Houthis, who believe they are winning the war and thus have no incentive to negotiate a ceasefire. Saudi Arabia and Lenderking portray the Houthis as uninterested in coming to the negotiating table, which is accurate. The Houthis are virtually certain to reject any negotiation defined by the terms of UN Security Resolution 2216, which requires that they give up their weapons and territory. Thus, for Riyadh and Washington to continue to propose ceasefires under this framework, while knowing full well that it will be unacceptable, amounts to the intentional prolonging of the war.

The Saudis and the Hadi government have lost the war. Their insistence that the Houthis accept their terms before they lift the blockade reflects their unwillingness to accept this fact. The U.S. government’s unwillingness to acknowledge that the position of the Hadi government — and therefore the Saudi position — is untenable, appears to be motivated by Washington’s animosity towards Iran. The government continues to frame Yemen through the lens of Iran, a position that reinforces Riyadh’s argument that it cannot accept a resolution to the conflict that permits the Houthis to remain in control of most of Yemen. Yet, despite six years of war and billions of dollars of resources to wage it, the Saudis must accept that they have lost. Unfortunately, decades of U.S.-Saudi partnership not only flooded the kingdom with tens of billions of dollars of sophisticated U.S. arms, training and other support, but also to have transferred to the Saudi military’s mindset something of the American military’s chronic inability to accept the reality of unwinnable wars.

If, as they claim, Riyadh and Washington are committed to ending the violence in Yemen, they will need to shift their approach. The Houthis are not interested in ending the violence, as it has offered them gains beyond what they thought possible.

The members of Congress who will hear Lenderking’s testimony must not accept at face value his insistence that the United States and Saudi Arabia are committed to peace in Yemen, when their actions so clearly demonstrate the opposite. Congress must use these hearings as an opportunity to demonstrate that Biden’s declaration on February 4 that “this war has to end” has not yet been borne out by his administration’s policies and actions.