As COVID-19 rages in the United States, shattering records for new daily infections, an inflection point may have been reached in how the rest of the world views the United States.

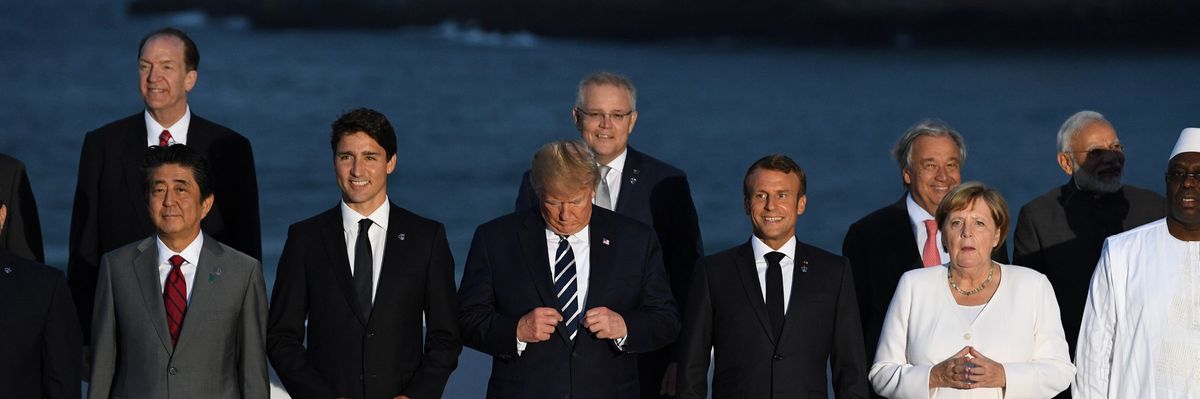

Granted, there already had been much in the first three years of Donald Trump’s presidency to cause dismay among foreigners, including his disdain for international institutions and longstanding international friendships and his disregard for U.S. obligations under international agreements. And much of his earlier response to the current pandemic caused foreign heads to shake and eyes to roll, such as being so obsessive about shifting blame to China that the G-7 could not issue a statement on the coronavirus because of the administration’s insistence on calling it the “Wuhan virus.”

What is distinctive about this moment is that, just as the pandemic is becoming worse than ever for the United States itself, it has become clear that Trump has abandoned efforts to control and defeat it. When leadership at the top is most needed, Trump has checked out — “moved on,” as some observers put it.

Those daily White House shows that were billed as coronavirus briefings even though Trump used most of the airtime for self-congratulations are a thing of the past. In other words, Trump isn’t even interested any more in pretending to fight the pandemic.

Trump is engaging in political activity that not only disregards efforts of others to fight COVID-19 but pointedly undermines those efforts. This pattern is exemplified by the latest detail to emerge from Trump’s recent rally in Tulsa. His campaign removed stickers that the arena’s management had placed on alternate seats to get attendees to keep their distance from each other. Thus, even though once the rally was under way the arena was only half full, most of the mostly maskless followers were seated elbow-to-elbow on the lower level.

Meanwhile, the vice president of the United States is given the job of going before cameras and speaking about a fantasy world in which the United States has COVID-19 well under control.

Americans have every reason to be thoroughly dismayed by Trump’s posture during this crisis. As the National Interest’s Jacob Heilbrunn puts it, that posture “is as immoral as it is feckless.”

But worry too about what all this is doing to America’s standing in the world. The European Council on Foreign Relations has just released results of a poll of 11,000 citizens in nine European countries that speaks to this issue.

About two-thirds of the respondents in most of the countries surveyed say their view of the United States has worsened during the pandemic. Only about two percent across the entire survey sample identify the United States as their country’s “greatest ally in the coronavirus crisis” — less than the number who named China.

The authors of the European Council’s report write that these results are not “simply one more indication of how strongly Europeans oppose Trump’s way of doing foreign policy.” Rather, they say, “If Trump’s America struggles so much to help itself, how can it be expected to help anyone else? If this domestic chaos continues, many Europeans could come to see the US as a broken hegemon that cannot be entrusted with the defense of the Western world.”

The COVID-19 pandemic is the first big global crisis within memory in which the United States is not even trying to lead efforts toward finding and implementing a solution. Unlike with, say, climate change or arms control, Trump’s impulse to do the opposite of whatever Barack Obama did cannot be the main explanation for the absence of effort and leadership, given that COVID-19 arose well after Obama’s term ended — although the same impulse would underlie the Trump White House’s apparent ignoring of the detailed pandemic response plan the Obama administration prepared.

An instructive comparison and contrast is with George W. Bush’s response to 9/11 and the resulting burst of public concern about terrorism. Bush’s posture disregarded how European governments had been ahead of the United States on many aspects of counterterrorism, and he launched under the rubric of so-called “war on terror” a disastrous offensive war in Iraq that became a major source of division between the United States and some of its European allies. But Bush did seize the moment and imparted a sense of purpose to his presidency and to the nation and beyond under the theme of fighting terrorism.

A president other than Donald Trump would have seized the current moment and tried to exercise leadership in a similar way in response to COVID-19. Such a president would be sort of an American Jacinda Ardern, scaled up to reflect the size and global clout of the United States rather than New Zealand.

Donald Trump has done nothing like that, mainly because of his solipsistic lack of a sense of public service or public interest. Once he failed to see a way for the pandemic to enhance his ego or his image, he lost any interest in fighting it. Even tens of thousands of American deaths are not sufficient to kindle such an interest.

Foreign governments and many foreign citizens realize that Trump is not to be equated with America, and for many reasons besides the pandemic they hopefully await regime change in Washington. But they reflect as well on what kind of political system could have put a Trump in the presidency and could put someone similar in it again. Global leadership cannot depend on the vicissitudes of broken domestic politics.