The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a close ally of Saudi Arabia and partner of the United States. With its own national interests, however, the UAE does not always share Riyadh’s and Washington’s perspectives on international issues, driving Abu Dhabi to take actions that sometimes veer away from key Saudi and US policies.

With diverse partnerships across an increasingly multipolar world, the UAE is adept at balancing other powers off each other in order to ensure that Abu Dhabi can maintain an independent foreign policy aimed at advancing Emirati interests. At times Abu Dhabi’s agendas are in greater alignment with non-western and non-Gulf states like Russia and China.

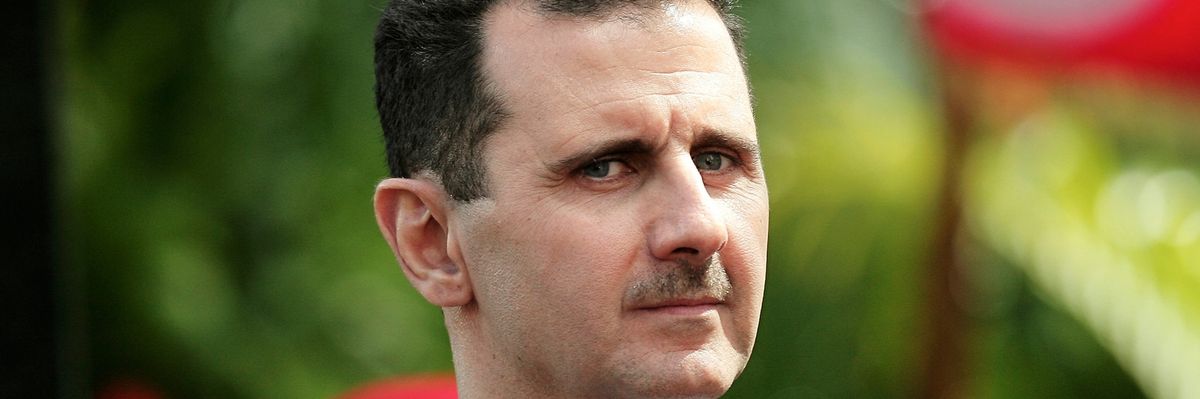

Abu Dhabi’s approach to Syria is a salient example. Rather than taking the same position on President Bashar al-Assad and his Ba’athist government as Saudi Arabia and the U.S., the UAE is much more in sync with Moscow, Beijing, and Tehran’s stance that Assad is a legitimate leader. When it comes to views about Islamist movements, as well as the protection of certain religious/ethnic minorities in Syria, Moscow and Abu Dhabi share much in common.

This is not a brand-new development. In contrast to other Gulf states and Turkey, the UAE refused to sponsor armed Islamist factions fighting Syria’s regime, although Abu Dhabi nominally supported the anti-Assad rebellion in the early stage of the Syrian crisis.

In 2015, however, when Russia intensified its direct military intervention in Syria’s conflict to tip the balance in Damascus’ favor, the UAE—unlike Saudi Arabia—did not object. In fact, two months after Russia’s intervention began, Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Anwar Gargash affirmed that Moscow was targeting a “common enemy” in Syria. As early as 2016, officials in Abu Dhabi began expressing its support, in principle, for the parties in Syria to negotiate a political solution to the conflict that would leave Assad in power.

Confirmation of the UAE’s view of Assad as legitimate came in December 2018 when Abu Dhabi reopened its diplomatic mission in Damascus. Since then, numerous meetings and speeches have further illustrated the extent to which the UAE has been backing efforts aimed at bringing Assad back into the Arab League and international community at large.

After the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the UAE’s de facto ruler, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed (MbZ), held a conversation with Assad in which he committed the Emirates to help Damascus deal with the virus.

On March 27, MbZ addressed this conversation in a tweet. “I discussed with Syrian President Bashar Assad updates on COVID-19. I assured him of the support of the UAE and its willingness to help the Syrian people. Humanitarian solidarity during trying times supersedes all matters, and Syria and her people will not stand alone.”

The MbZ-Assad exchange marked the first time since 2011 that an Arab leader spoke personally with Assad and later publicized that conversation. Without question, the UAE sees a continuation of Assad’s presidency as Syria’s best option, at least for the time being. From Abu Dhabi’s perspective, the COVID-19 crisis is yet another reason to try and push more governments worldwide toward this position.

(The UAE has responded to the pandemic by also giving support to Iran, which is the Middle East’s hardest-hit country. Such humanitarian assistance to the Islamic Republic is yet another example of Abu Dhabi demonstrating its willingness to take action that is not in lock-step with Riyadh's and/or Washington’s agendas).

The Syria-Libya Nexus

Earlier this month, Middle East Eye published an article by David Hearst that raised many eyebrows. The gist of the article was that MbZ sought to push Assad toward re-launching his offensive to take back Idlib despite the Turkish/Russian-brokered ceasefire (“Sochi 2.0”) negotiated in March following direct military clashes between Turkish and Syrian forces. According to Hearst, the UAE offered Assad three billion dollars to break the ceasefire.

A number of Middle East experts who have spoken with this author cast doubt on the story’s credibility, finding it difficult to believe that such a deal was in the works. Nonetheless, the UAE has been taking numerous steps in Syria to counter Turkey, and challenging Ankara’s interests and agendas in Idlib could be the latest one. According to the Middle East Eye article, MbZ was motivated by, first, a desire to “tie the Turkish army up in a costly war in northwestern Syria”, and, second, Abu Dhabi’s quest to “stretch the resources of the Turkish army and distract Erdogan from successfully defending Tripoli” from the UAE-sponsored Libyan National Army (LNA) of Gen. Khalifa Haftar.

With a growing number of Syrian mercenaries fighting in Libya—both for the Turkey-backed Government of National Accord (GNA) and the UAE-sponsored LNA—the two Arab countries’ crises are becoming increasingly linked. Both Syria and Libya are conflicts where Abu Dhabi and Ankara’s strategic clashes have become increasingly pronounced over the past several years.

The reopening of the Libyan embassy in Syria in March (eight years after its closure in the aftermath of Qaddafi’s fall) was significant in the sense that the Haftar-allied administration in eastern Libya -- not the North African country’s UN-recognized government in Tripoli -- is represented in there. This development suggested the establishment of an anti-Turkey/anti-Muslim Brotherhood partnership between Damascus and the House of Representatives in Tobruk.

As long as Ankara and Damascus remain in conflict, and the unsustainable situation in Idlib persists, the crises in Syria’s northwestern province will continue putting pressures on Ankara that other states, such as the UAE and Egypt, can exploit in order to weaken Turkey’s position. For Assad, the growing number of Arab states that accept his continued rule is a welcome development, especially as he looks for ways to deter what may likely soon be Turkey’s fifth military incursion into northern Syria since August 2016.

What remains to be seen is how the U.S. reacts to the UAE’s rapprochement with Damascus. Given the Trump administration's support for Turkey’s Operation Spring Shield earlier this year, it is clear that Washington and Abu Dhabi are not on the same page when it comes to Assad and the crisis plaguing Idlib. Yet there is hardly any doubt that the situation in Syria has created more common ground between the Emirates and Russia, with both countries favoring strategies that rely on working with Assad’s government to eradicate groups such as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham.

Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org