With the New Year, the U.S. presidential election season is in full swing. Historically, that has meant that, with rare exceptions, U.S. foreign policy takes a back seat. Indeed, given that few Americans actually vote for a candidate or party on the basis of foreign policy, sensible seekers of the presidency will do and say the minimum needed to satisfy a few interest groups and the hungry media. They then get on with the bread and butter business of politics: the economy and other domestic issues.

That rule of thumb seems unlikely to prevail this year, and the dramatic change can be unfortunate for U.S. interests in the world and the overall conduct of foreign policy.

During the Cold War and for a while afterward, in years divisible by four much of the world quieted down, waiting to see who would win the U.S. presidential election. Wisdom dictated not roiling the political waters in the United States, lest the administration in power do something foolish for electoral gain. The term of art is “October Surprise,” based on the idea that a sitting president might either manufacture or exploit a foreign crisis for electoral gain as commander-in-chief.

Following the end of the Cold War and more recently as U.S. influence in the world has been relatively declining — though not military power and emphasis on it — the world has stopped ”quieting down” to see how the U.S. presidential election will turn out.

At the same time, this year U.S. domestic politics will have a greater impact than usual on the way that U.S. foreign policy is conducted. This will cut both ways: first what President Donald Trump is doing against long-term U.S. foreign policy interests in order to maximize his electoral support; and second, what Democratic opponents are doing with foreign policy issues to try getting rid of Trump as fast as possible. Both efforts can cause lasting problems for U.S. foreign policy or at least missed opportunities.

Iran and the Middle East

Two parts of the world stand out. First is the Middle East and especially Iran. Even before he became president, Trump put Iran on his hit list. Some of that could be an effort to undercut one of President Obama’s signal achievements, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) with Iran, which effectively trammeled its capacity to get nuclear weapons. By abrogating the JCPOA, Trump found himself at odds with all the other signatories to the agreement, but so what? They don’t vote in U.S. elections and the Americans who applauded his action do. Trump was supported by the relatively minor Arab/oil lobby (notably funded by Saudi Arabia and the UAE), but much more so by the Israel lobby and especially, from Trump’s perspective, those evangelicals who see the Israel issue in terms of their belief in the End of Days.

The problem for both Trump and the United States is that his taking steps that focus almost exclusively on military instruments regarding Iran, which supposedly underscore American “resolve,” is a dangerous game. It depends on a total commitment of the Iranian leadership not to seek an open conflict with the United States, as well as tight Iranian command-and control, especially over the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps. It also depends on Trump being able to sound the tocsin of war without its actually coming to pass: a delicate balance. In any event, the result is a further militarization of U.S. Middle East policy and a freezing of diplomacy. This is likely to have long-term, negative consequences for U.S. interests.

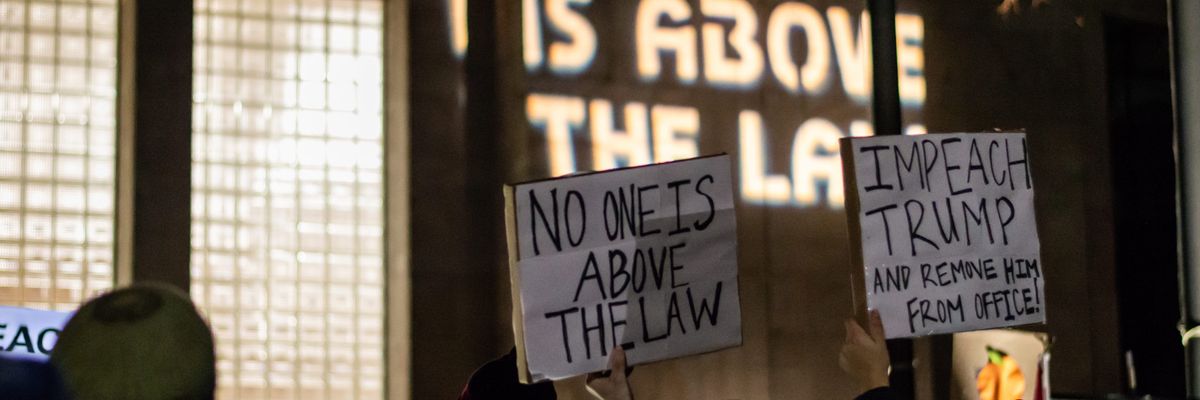

Impeachment – and Russia/Ukraine

On the other side of the coin – the Democrats – Russia stands out and, related to it, Ukraine. Since before Trump was inaugurated, Democrats were calling for his impeachment, and that hinged in major part on Russia, including Trump’s so-called “bromance” with Vladimir Putin. Two motives stood out. First was for Democrats to find a way to explain why Hillary Clinton lost the election. But even with Russian “interference” in the U.S. 2016 election, it stretched credulity to believe that that proved decisive; it also assumed that large numbers of Americans could be easily duped. Second, the Russia factor became important as a means for getting rid of Trump through impeachment. For months, the focus was on the Mueller investigation, which failed to provide the needed smoking gun, at least with enough popular appeal to produce a mass movement to remove Trump from office.

Ukraine then came along to fill that space. While what Trump has done regarding Ukraine very likely meets the test of “high crimes and misdemeanors,” the Democrats did not start with Ukraine and then talk about impeachment, but the reverse: Ukraine-gate became the instrument to fulfill a previously determined purpose. Its’s a big gamble. Will impeachment, which will not lead to Trump’s removal from office by the Senate, pay off in November’s polling because of all that has been revealed? After three years of “wolf, wolf,” that is not a sure thing.

What is a sure thing is that in this area, U.S. foreign policy has been paralyzed for three years in the search for means to try avoiding a new cold war with Russia and, indeed, to do what must be done: to recognize that Russia will not forever be the supine, defeated power in the Cold War. George H.W. Bush understood that with his grand strategy of pursuing a “Europe whole and free” and at peace. Bill Clinton followed suit for the first part of his presidency. Then the effort died, not just on the Russian side (Putin), but also miscues on the American side.

Discussion in the United States has thus deviated from any emphasis on diplomacy with Russia and now focuses almost entirely on military measures. This is not just at NATO (where some deterrent deployments were needed following Russian military actions in Crimea and elsewhere in Ukraine) but also in the Democrats’ current case against Trump: that he held up lethal military aid to Ukraine that was vital not just for its government but also for U.S. interests. Notably, the Obama administration, rightly or wrongly, had reached the opposite conclusion.

In sum, the chances are now miniscule that U.S. leaders — both Trump and the Democrats — will put the nation’s interests ahead of domestic politics, in at least the two areas of Iran and Russia, where diplomacy is dead at least for the time being. We can only hope that next year, when the presidential election is behind us, serious people will again assess what is best for the United States, including putting diplomacy at least on a par with military instruments. Even that is far from likely.