In an interview with the French weekly Le Nouvel Observateur, a former White House national security advisor, renowned for his hatred of Soviet Communism, was asked whether he regretted his idea to aid the Afghan mujahideen with a secret money and weapons pipeline that started flowing months before the USSR invaded in late December 1979.

The interview took place in 1998, five years after Islamists who had been trained in Afghanistan detonated a bomb in the parking garage under the World Trade Center, killing six people and injuring more than a thousand.

“Regret what?” scoffed Zbigniew Brzezinski. “What is more important in world history? The Taliban or the collapse of the Soviet empire? Some agitated Muslims or the liberation of Central Europe and the end of the Cold War?”Three years later, terrorists struck the Twin Towers again, provoking the United States to wage a global “war on terror” that Brzezinski himself would soon condemn for its excesses.

From 1979, however, as the Pakistani journalist Ahmed Rashid has noted, “none of the intelligence agencies involved wanted to consider the consequences of bringing together thousands of Islamic radicals from all over the world” to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan. The specific quote about stirred-up Muslims does not appear in Edward Luce’s mostly convincing, crisply written “Zbig: The Life of Zbigniew Brzezinski, America’s Great Power Prophet.” This is a minor omission.

Luce, an accomplished journalist at the Financial Times, seriously engages with this critical turning point in the Carter administration’s prosecution of the Cold War, an episode whose unintended consequences ripple to this day. This does not mean American Cold Warriors could or should have foreseen the spawning of al-Qaeda and 9/11/2001. What mattered was the way Brzezinski’s Soviet obsession could obscure the difference between worthwhile fights and sideshows in what he regarded as an obligatory contest for global primacy.

For the Polish-born, Ivy League intellectual who became President Jimmy Carter’s grand strategist, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan was an I-told-you-so moment that proved détente was a ruse by Moscow to pursue Third World adventurism. This was unacceptable to a man who, since the outset of his scholarly career, believed Washington needed a usable strategy to accelerate the Soviet Union’s inevitable collapse.

Luce does cite an excerpt from the French interview where Brzezinski admitted the early clandestine support for the Muslim insurgency was meant to induce a Soviet invasion, although he “insisted he had been inaccurately quoted and asked the French paper to retract it.” Whatever he said two decades after leaving power, Brzezinski’s ideas and influence have plenty to teach us by offering “a window on how the world works and what happens in history,” says Luce.

Amid today’s global chaos, there are echoes of the cascading emergencies that consumed Carter’s last two years in the White House, none more politically damaging than the Iranian hostage crisis.

Today, we are warned that an alliance of autocracies threatens the rules-based order. In the late 1970s, Brzezinski identified an “arc of crisis” from Southeast Asia through the Middle East to the Horn of Africa, where he wanted to counter Soviet military support for Ethiopia in a war against Somalia over the Ogaden desert.

“If Carter had taken his advice to oppose the USSR in the Horn of Africa, the Soviets might not have invaded Afghanistan, Brzezinski kept telling people,” Luce writes. “He maintained that America’s passive reaction to Soviet moves in the Horn of Africa and elsewhere gave Moscow the confidence to invade Afghanistan.” Today, Washington must back Ukraine lest China become emboldened to absorb Taiwan, a sort of psychological domino theory that transcends time.

With détente dead and SALT II now buried “in the sands of Ogaden,” Carter’s spine was stiffened by Soviet perfidy. The president’s tutor in world affairs had defeated the State Department in the endless wrangling over the direction of U.S. foreign policy vis-à-vis Moscow. And it produced the most preposterous claim of Carter’s excruciating stint in the White House: The invasion of Afghanistan, the president said, “could pose the most serious threat to the peace since the Second World War.”

This hallucination led to the Carter Doctrine, formulated by Brzezinski and announced in the 1980 State of the Union address, to militarize U.S. management of the Middle East and its oil, a move whose consequences would make possible future catastrophes. Even at the time, the threat seemed inflated, unless one believed the Red Army could bound from the mountains of Afghanistan and control the oil-rich Persian Gulf thousands of miles away, like the little plastic armies in the board game Risk.

U.S. backing for the anti-Soviet jihad is but one drama in Edward Luce’s valuable study of a man whose arrogance, ego, and relentless nature made enemies across the political spectrum, none more influential than “frenemy” Henry Kissinger, who often appears as a two-faced schemer in these pages.

Most of the events covered here belong to the past century, but continuities abound. For instance, for the outrage of backing Palestinian autonomy, Brzezinski was accused of being anti-Israel, a charge Luce concludes was unfounded. Carter’s foreign policy guru was nonetheless fearless in calling out the pro-Israel lobby. How ironic, Luce notes, that his critics routinely accused Brzezinski of divided loyalties because he was proudly Polish. They did not appreciate it, however, when he pointed to their pro-Israel fanaticism.

The first and only Polish-born national security adviser, Zbig was driven by the supposed betrayal by FDR at Yalta and the “hollow militancy of rollback,” Luce says. Yet Brzezinski was no warmonger. He understood the U.S. could only help liberate Eastern Europe peacefully. The author credits his sharp diplomacy with preventing a Soviet invasion of Poland in 1980. He applied pressure on both the Kremlin and the Solidarity movement, advising the latter not to do anything to provoke the Politburo.

Brzezinski believed the Communist empire would unravel because of its “nationalities problem.” Rather than Soviet citizens, there were Ukrainians, Poles, Lithuanians, Uzbeks, etc., who had never wanted to be trapped in Moscow’s grip. This is where he earned his reputation as a “prophet.” Yet it was not Afghanistan — adjacent to the “weak underbelly” of the Muslim-majority Central Asian republics — that led to the USSR’s demise. The scholar Artemy Kalinovsky has argued that the quagmire was costly but sustainable, and there was little public pressure in an authoritarian police state to withdraw.

Luce is correct to emphasize that Gorbachev’s failed economic reforms were the true catalyst of internal collapse.

When it came to the Soviet empire, however, Carter and Brzezinski’s commitment to the 1975 Helsinki agreements contributed to the Eastern Bloc’s disintegration a decade later. Their support for the dissidents in captive nations behind the Iron Curtain, such as Czechoslovakia’s Charter 77, was entirely consistent with Carter’s human rights stance. It is therefore surprising that Luce scarcely mentions the administration’s policy in bloody El Salvador. Then again, “Brzezinski shared with Kissinger a remarkable lack of curiosity about the rest of the Western Hemisphere.”

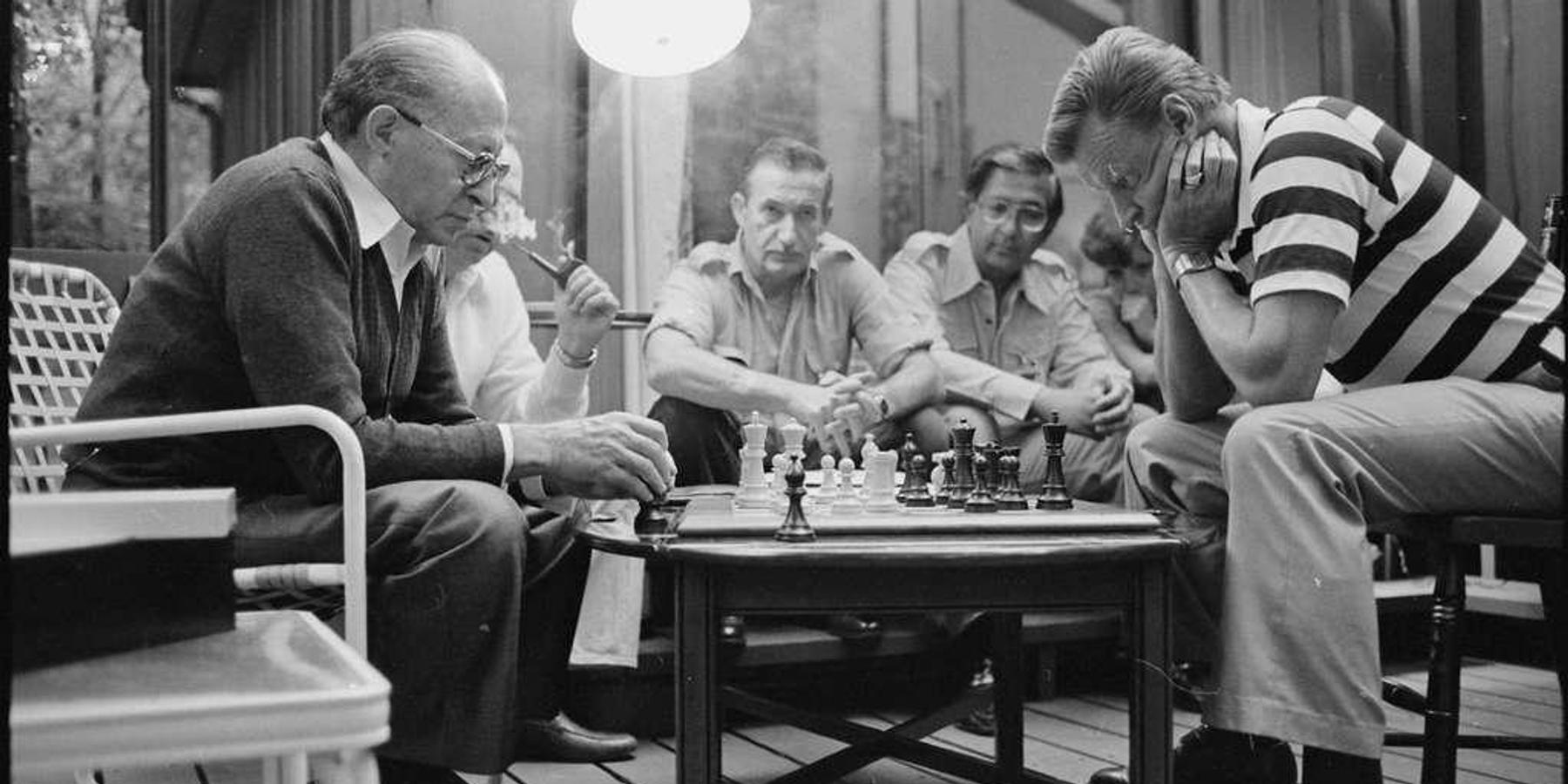

As the world appears headed into a new era of anarchy, Edward Luce’s cradle-to-grave biography of Zbigniew Brzezinski, an ardent anti-Communist capable of tactical flexibility, reminds us how the unforeseen — as when Carter’s people were blind to the popular anger toward the Shah of Iran — shapes history as much, if not more so, than the strategists who try to master the global chessboard. Therein lies the danger of comparing great power competition to chess. In a boardgame, players must always move or resign. In a dangerous world, sometimes it’s wise not to make a move.