How did this suddenly become the summer of “the draft”?

There are a number of proposals in the annual defense policy bill (National Defense Authorization Act) that deal with the subject. There is one to expand selective service registration to women. Another that would make Selective Service registration for American men “automatic.”

Still another proposed amendment to the NDAA, which has also been introduced as a freestanding bill, S. 4881, would repeal the Military Selective Service Act entirely. Meanwhile, the Center for a New American Security just published an exhaustive blueprint for modernizing mobilization, including readiness to activate conscription.

All this talk has compelled “fact checkers” to insist that no, the U.S. government isn’t suddenly “laying the groundwork” for a draft.

But saying the U.S. isn’t preparing for a draft is like saying it isn’t preparing for nuclear war. Just as the Department of Defense is tasked with maintaining readiness to initiate nuclear strikes whenever the Commander-In-Chief so orders, the Selective Service System has the sole mission of maintaining readiness to hold a draft lottery within five days and start selecting draftees and sending out notices to report for induction whenever Congress and the President so order.

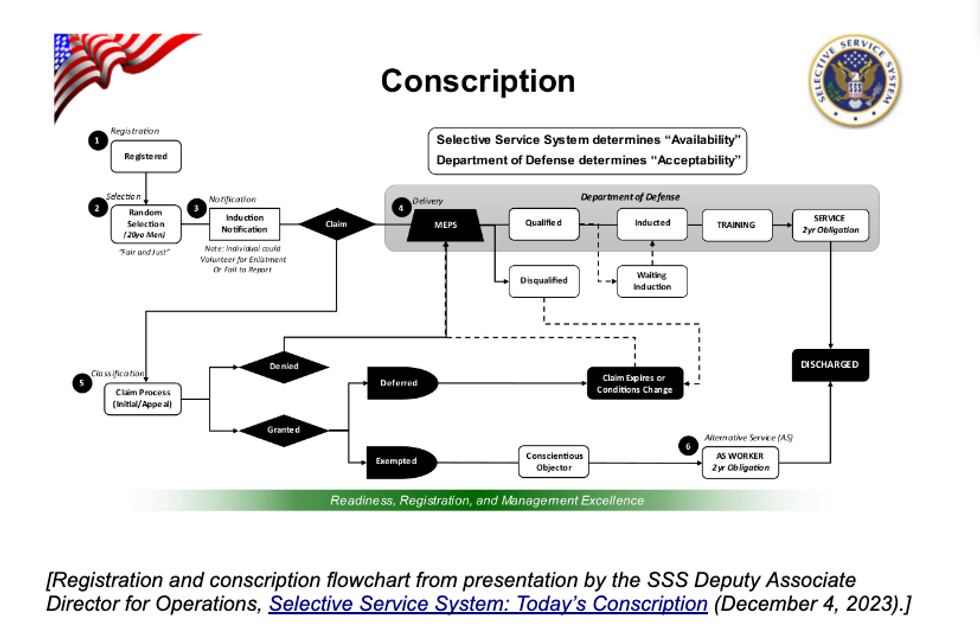

As such, there are currently ten thousand draft board members who have been appointed and trained to adjudicate claims for deferment or exemption. As recently as this month, states have been openly seeking volunteers to fill empty slots. And both the SSS and hawkish think-tanks have been war-gaming the government’s contingency plans to activate a draft.

There’s room for argument about how likely it is that the U.S. would launch nuclear missiles or activate a draft. But there’s no question that it’s planning and preparing for both, as it has been for decades. It would seem that after years of atrophy, the government is stepping up its attention to military mobilization and readiness for a draft.

Maybe it’s time to ask whether more easy and efficient ways of tapping into human capital for war make it easier to get into one and whether it is in our best interest to do so.

Mobilizing an army “on demand”

A staff memo prepared for a 2019 meeting of the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service (NCMNPS) noted that “The ability of SSS to execute a draft effectively based on its existing database and procedures has not been tested in recent decades.”

The NCMNPS commissioned no research on this or any other issue, instead reserving as much as possible of its budget for a planned publicity and lobbying blitz most of which it was unable to carry out due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Following the dissolution of the NCMNPS, Congress included a provision in the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2022 directing the DOD to conduct a comprehensive mobilization exercise which would “include the processes of the Selective Service System in preparation for induction of personnel into the armed forces under the Military Selective Service Act, and submit to Congress a report on the results of this exercise.”

The DOD was required to complete this exercise by September 30, 2023, but the SSS told me recently that the DOD has yet to schedule it.

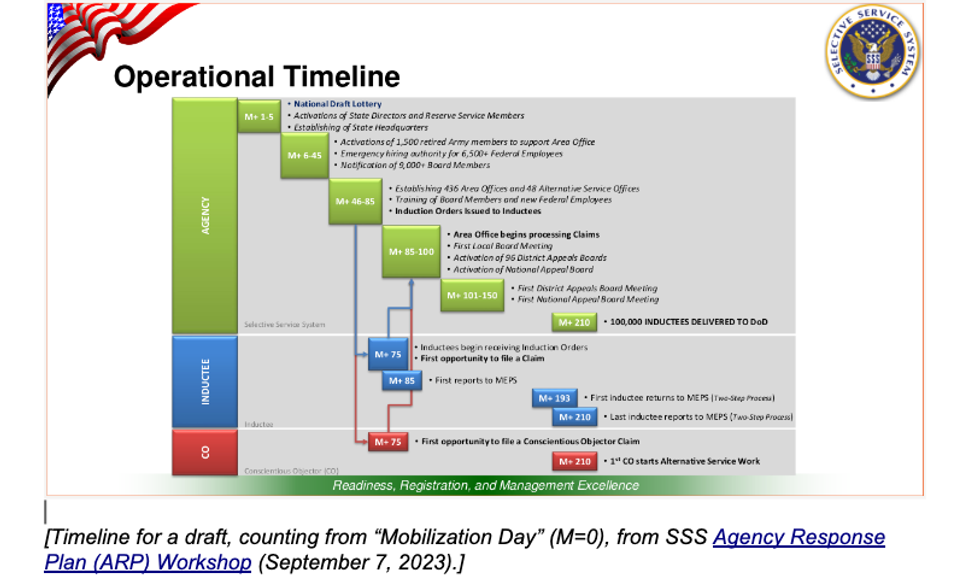

The SSS has, however, released records of some of its internal contingency plans and exercises as well as of an interagency planning and coordination workshop it convened in December 2023.

Enforcement is conspicuously absent from these plans. The possibility that an individual could fail to report for induction is relegated to a footnote, with no indication of what would happen in that event. Nonregistration and other modes of resistance aren’t mentioned at all.

The Department of Justice – to which suspected violators would be referred -- was not included in the interagency workshop. The keynote speaker from the DOD at that workshop pointed out that the SSS has “No clear understanding in the supply of manpower due to undetermined criteria” including “How many would attempt to dodge the draft?”

In 2021, the SSS referred 238,679 names of suspected non-registrants to the DOJ after they didn’t respond to threatening letters. None of them were investigated or prosecuted, or could be prosecuted without evidence of actual knowledge and criminal intent. Nor were any of the millions of other suspected non-registrants referred to the DOJ since 1988.

In 2022, the DOJ told the SSS to stop sending any more referrals of nonregistrants, presumably because the DOJ wasn’t going to do anything with them. The DOJ has no idea what it would do if it were called upon to try to enforce induction orders.

Meanwhile recently the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) conducted its own tabletop exercise in activating a draft, including SSS and DOD staff as well as civilian military strategists. The CNAS report on that exercise, released last month, helps show how keeping the draft in the U.S. arsenal enables more bellicose foreign policies, even if a draft is unlikely and the contingency plans for it wouldn’t be workable.

Better draft, more hawkish policies?

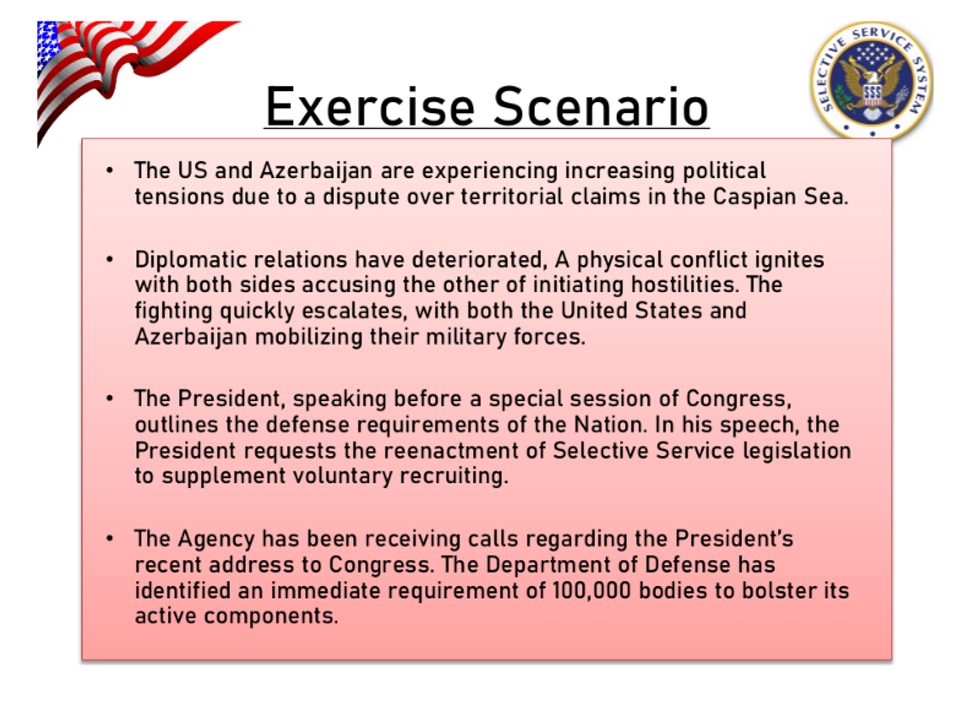

In its own 2023 table top exercises, SSS used the scenario of a war between the U.S. and Azerbaijan in the Caspian Sea, after which “the Department of Defense identified an immediate requirement of 100,000 bodies.”

Meanwhile, CNAS imagined a “large-scale invasion of Taiwan” by China, followed by a Chinese attack on “a location between San Diego and Los Angeles.” At its public hearings on the draft in 2019, NCMNPS considered “a Red Dawn scenario where we are being attacked from both Canada and Mexico.”

Is the People's Liberation Army really going to land on the beaches of Southern California? Would activating a draft to fight a war in Taiwan or the Caspian Sea be an appropriate or effective military tactic — or a recipe for another Vietnam, Iraq, or Afghanistan?

It’s tempting to think that these scenarios are so improbable that contingency planning for a draft that won’t be activated is unimportant. But CNAS, SSS, and DOD strategists emphasize that readiness to activate a draft is, in and of itself, critical to U.S. deterrence.

But as with nuclear weapons, to speak of readiness for a draft as a “deterrent” is also to speak of it as a threat. Like nuclear warheads, the draft is used as a weapon when it is used as a military threat – whether or not the threat of nuclear war or of a draft is ever carried out.

Proponents of draft registration and readiness for a draft such as CNAS, the NCMNPS, and some in the Pentagon and Congress argue that if the great-power enemies of the U.S. believe that we are able and willing to activate a draft, we can use that threat of draft-enabled rapid and total military escalation as a tool of diplomatic and military policy.

In other words, the availability of the draft helps enable the U.S. to threaten to crush any opposition to U.S. hegemony with rapid and overwhelming military escalation. And the perceived (although misguided) ability to rely on those threats makes it easier not to consider diplomatic or other alternatives to force as a response to conflicts.

But that also means that, conversely, ending planning and preparation for a draft is a tool we can use to rein in the rush to total war by removing the draft from the arsenal of US military threats, forcing military planners to consider the degree of popular support for possible wars, and slowing the capacity of the U.S. to escalate to total war.

Have the U.S. military errors of the last fifty years consisted more of being too slow to commit fully to war? Or of too rapid resort to military engagements that have led to quagmires rather than quick fixes?

Many of the above-mentioned scenarios being used to support the need for readiness for a draft are about military engagements abroad, not attacks on the U.S. homeland. As Sen. Rand Paul said this past week in reintroducing the Selective Service Repeal Act, “If a war is worth fighting, Congress will vote to declare it and people will volunteer.” In the case of an actual threat to the U.S., the limiting factor in mobilization would be the capacity of the military to rapidly train or integrate a massive number of volunteers. That’s not a problem a draft would solve.

Should we be putting in place mechanisms that make it easier to rush into another large overseas military adventure more quickly, on a larger scale, and with less need to wait and see if the public supports the war or will vote with its feet by enlisting to fight it?

We’ve seen this dynamic play out in Russia, where the presumed ability to rely on conscription as a fallback helped embolden Putin’s hasty military over-reach into Ukraine. Do we want the U.S. to make the same strategic mistake?

- Congress moves to make Selective Service automatic ›

- A war draft today can't work. Let us count the ways. ›

- US military draft sign-ups plunge in 2 years | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Congress quietly moves US closer to military draft | Responsible Statecraft ›