“A raider attack on the U.N. Security Council.” This was the explosive accusation leveled by Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov this week. His target was the U.N. Secretariat and Western powers, whom he blamed for what Russia sees as an illegitimate attempt to restore the nuclear-related international sanctions on Iran.

Beyond the fiery rhetoric, Ryabkov’s statement contained a message: Russia, he said, now considers all pre-2015 U.N. sanctions on Iran, snapped back by the European signatories of the 2015 nuclear deal (JCPOA) — the United Kingdom, France, Germany — “annulled.” Moscow will deepen its military-technical cooperation with Tehran accordingly, according to Ryabkov.

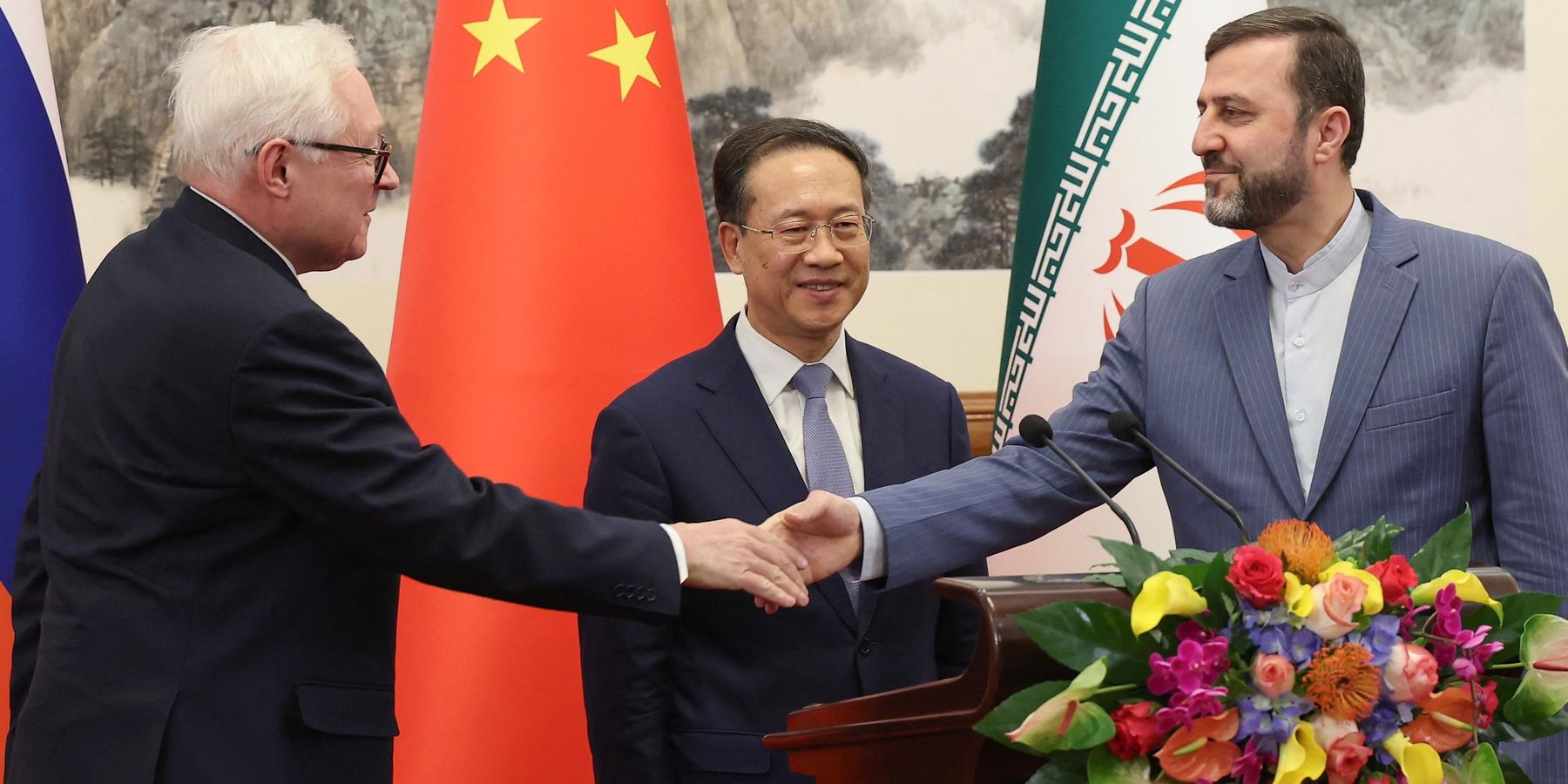

This is more than a diplomatic spat; it is the formal announcement of a split in international legal reality. The world’s major powers are now operating under two irreconcilable interpretations of international law. On one side, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany assert that the sanctions snapback mechanism of the JCPOA was legitimately triggered for Iran’s alleged violations. On the other, Iran, Russia, and China reject this as an illegitimate procedural act.

This schism was not inevitable, and its origin reveals a profound incongruence. The Western powers that most frequently appeal to the sanctity of the "rules-based international order" and international law have, in this instance, taken an action whose effects fundamentally undermine it. By pushing through a legal maneuver that a significant part of the Security Council considers illegitimate, they have ushered the world into a new and more dangerous state. The predictable, if imperfect, framework of universally recognized Security Council decisions is being replaced by a system where legal facts are determined by political interests espoused by competing power blocs.

This rupture followed a deliberate Western choice to reject compromises in a stand-off with Iran. While Iran was in a technical violation of the provisions of the JCPOA — by, notably, amassing a stockpile of highly enriched uranium (up to 60% as opposed to the 3.67% for a civilian use permissible under the JCPOA), there was a chance to avert the crisis. In the critical weeks leading to the snapback, Iran had signaled concessions in talks with the International Atomic Energy Agency in Cairo, in terms of renewing cooperation with the U.N. nuclear watchdog’s inspectors.

Simultaneously, Russia and China put forward a resolution to technically prolong the validity of Resolution 2231— which codifies the JCPOA — for six months. This was a direct attempt to buy time for a diplomatic solution that could have reunited all parties, much like the original 2015 deal.

This proposal was rejected by the Europeans, encouraged by the U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio (the U.S. itself is not part of the JCPOA following President Trump’s withdrawal from the agreement during his first term in 2018).

European motivations for punishing Iran extend beyond its stockpiles of highly enriched uranium. The central factor is Iran's backing of Russia in the war in Ukraine that Europe has defined as an existential threat to its security. Within this strategic framework, jeopardizing relations with Washington to accommodate Tehran was never a viable option.

But the European nations that insisted on triggering the snapback must now ask themselves: are they in a better situation today? Not only have they created conditions for the Iranian nuclear program to go completely dark, but they have also dismantled an international consensus on the Iranian nuclear program — which played a key role in convincing Iran to negotiate and sign the JCPOA in the first place.

By contrast, now, where there was unity and pressure, there is a fundamental rupture. Two of the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council now officially operate on the notion that the snapback never happened, creating a far less predictable and more fragmented world.

The old U.N. sanctions against Iran are biting not so much in terms of economic hardship (which mostly stems from the effects of the U.S. secondary sanctions anyway), but in terms of re-imposition of the arms embargo and restrictions on nuclear and missile technology.

This is precisely where Ryabkov’s declaration becomes operational. His statement is a clear signal that Russia no longer feels bound by these restrictions. To be sure, relations between Russia and Iran are characterized by mistrust, as many in Tehran are disappointed with what they perceived as a lack of Russian support during the 12-day war with Israel in June.

However, such assumptions are not what should guide European policy — by triggering the snapback, they have voluntarily given up any leverage over Russian-Iranian relations. The snapback will inevitably push Tehran closer to Moscow out of necessity, regardless of their underlying tensions. If Iran needs advanced fighter jets, missiles or an upgrade of its air defense systems, it can now theoretically procure them from Russia or China within the framework of this new, competing legal reality. What was once a universal prohibition is now a contested rule.

The most dangerous outcome is the precedent this sets for both non-proliferation and international law. The Security Council’s authority derives from its members’ collective acceptance of its decisions. When that consensus shatters, its resolutions become merely non-binding suggestions from one party or another.

We are now in uncharted territory. The U.S. and EU may attempt to use the pre-2015 resolutions as a legal basis for new unilateral measures. Meanwhile, Russia and China will use their own interpretation of the new legality to justify deeper strategic and military cooperation with Iran. The original goal of the JCPOA — a unified international front to ensure Iran's nuclear program was of exclusively civil nature — has been shattered, replaced by a high-stakes confrontation with unpredictable consequences for the global non-proliferation regime.

The Iran snapback was intended to pressure a single nation. Instead, it has successfully split the very framework of international law in two. Ryabkov’s “raider attack” accusation is not the cause of this crisis, but its most vivid symptom. The U.N. Security Council no longer looks like a single entity but rather a fractured body presiding over competing realities. And there doesn’t appear to be a clear mechanism to put it back together.