What’s worse than the Pentagon spending taxpayer dollars on golf courses? Spending taxpayer dollars on golf courses that nobody uses.

Even as the Department of Defense renovates some of its 145 golf courses, the Army acknowledged in a new Pentagon study on excess capacity that it owns at least six facilities labeled “Golf Club House and Sales” that almost no one uses. The Navy owns at least two more golf facilities that it listed as underutilized.

But the problem goes far beyond golf courses. The Pentagon oversees some $4.1 trillion in assets and 26.7 million acres of land — a sprawling network of military installations across the United States and the globe. Wasted space and resources in that network could be squeezing taxpayers out of billions of dollars.

A Defense Department official familiar with the data included in the new report, which is only available for viewing in person at the House and Senate Armed Services Committees in Congress, explained to RS that the Pentagon’s problem of empty buildings has gotten out of hand.

“Most installations are incentivized to hang onto empty or partially empty spaces until they know for sure that the building is totally failing,” they said. Otherwise, installations will lose their funding.

In other words, the Pentagon has a phantom infrastructure problem made up of empty storage warehouses and training facilities that collect dust. The only thing real about them is the cost, brought to you by the U.S. taxpayer.

But just how bad has this problem gotten? Well, the Pentagon itself doesn’t have a consistent answer, meaning the real number of underused facilities could be much higher.

The last time the Pentagon tried to answer this question publicly was in a 2017 infrastructure capacity report, which found that roughly 20 percent of the Pentagon’s infrastructure was excess to need.

However, this new report — responding to a requirement in the Fiscal Year 2024 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which the House and Senate Armed Services Committees just received this month — tells a different story. Taken together, these two reports reveal flawed and incongruous systems for assessing the Pentagon’s costly excess infrastructure capacity, which in turn serve to undermine the case for reducing this excess infrastructure through a new round of Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC).

In the new report, dated September 2024, each of the military service branches responded separately to a list of ten prompts included in the NDAA. One of these prompts seeks information on the total number of excess assets (i.e. buildings) and their total square footage. Another requests information on “the number of underused facilities with the associated use rate…”

One of the more obvious shortcomings of this report is that the Army is the only military service that listed total assets and their square footage alongside excess assets and their square footage; the Navy and the Air Force simply listed excess assets and square footage, obscuring the percentage of their assets that are excess to need. By searching a General Services Administration (GSA) database of government property, we were able to correct for this shortcoming (though numbers represent our best estimate because GSA’s methodology for assessing total assets may differ from the Pentagon’s).

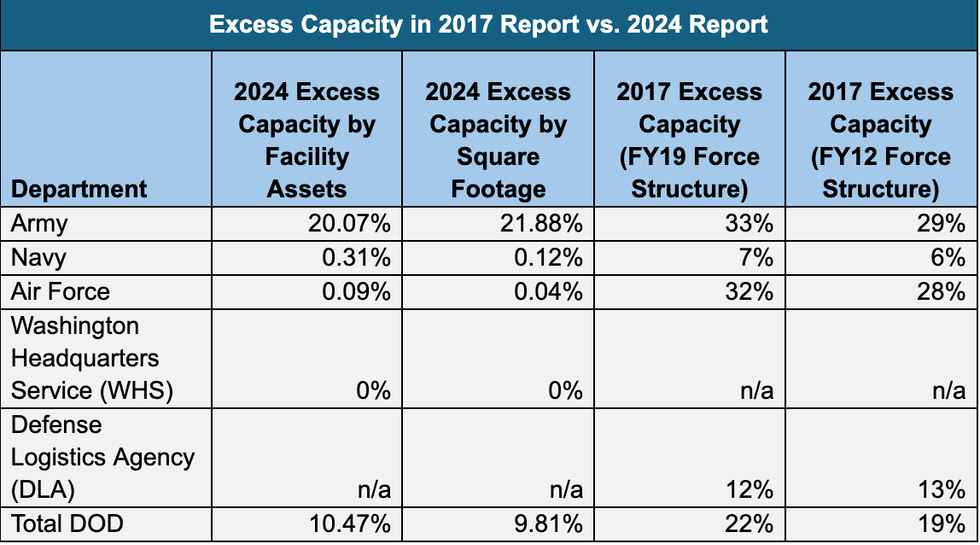

The following table compares the 2024 report’s findings (and conclusions drawn from them based on GSA data) to findings in the 2017 report.

Taken at face value, this data appears to show that the Pentagon’s excess infrastructure has shrunk significantly in the seven-and-a-half years since its last public report on infrastructure capacity.

In particular, the Air Force may appear as if it has unlocked the secret to shedding excess capacity without the politically challenging work of a new BRAC process, having cut excess capacity from around 30 percent to less than 0.1 percent in under eight years. That news might come as a surprise to Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David Allen, who has been pointing to the Air Force’s roughly 30 percent excess infrastructure in a dispute with lawmakers over the Pentagon’s backlog of deferred maintenance at its facilities.

Still, the new data would be welcome news, if it were sound. Unfortunately, methodological differences between the reports make it difficult to assess progress, and insight from an official familiar with the data suggests the new numbers are severely underestimated.

For one, Pentagon officials responsible for listing excess capacity in the report are incentivized to underreport, according to the Department of Defense official who was granted anonymity to discuss the report.

“Facility utilization data included in the report varies widely in its accuracy and timeliness,” they said. “The information is self-reported, labor-intensive to compile, and installations have an incentive to avoid declaring facilities as ‘excess’ because once they change the facility status from ‘active’ to ‘excess,’ the projected sustainment funding associated with the square footage of the facility (or other unit of measure) will drop by 85%.”

This not only makes access to accurate information exceedingly difficult, but it also creates a perverse incentive structure in which installations hang onto empty and partially empty spaces.

“For instance,” the official explained, “if an installation is receiving $250,000 annually in sustainment funding for a warehouse — but the base no longer needs or uses the warehouse — the installation commander and their public works director will likely keep the warehouse listed as ‘active’ rather than changing its real property status as ‘excess’ to avoid slashing their sustainment funds down to a meager $37,500 per year. While it’s empty and locked or boarded up, they can spend almost nothing on it, but still use the $250,000 a year for the installation and use that money on other needed repair and sustainment projects across the base.”

The new study acknowledges some issues with the data. For instance, the Army reported that it lacks “the manpower to do required utilization studies.” In other instances, military departments just blatantly ignored the data request, providing incomplete answers. But the study does not address the fundamentally perverse incentive for installations to underreport excess capacity.

The 2017 report by contrast, paints a much starker picture regarding Pentagon waste. Rather than detailing individual installations, that study assessed excess capacity by service using a baseline year of 1989 to maintain consistency with earlier infrastructure capacity reports.

However, the report itself still underscores that its findings are highly conservative, pointing to its assumption that there was not excess capacity in 1989. As the methodology section explains, “using 1989 as a baseline indicates the excess found in this report is likely conservative because significant excess existed in 1989, as evidenced by the subsequent BRAC closures.”

The Pentagon has said that past BRAC rounds are collectively saving taxpayers some $12 billion per year. Congress should work to authorize a new round of BRAC, which could save taxpayers additional billions of dollars per year, without further delay.

As a start, lawmakers should include a new reporting requirement in this year’s NDAA that requires the Pentagon to report on its excess infrastructure capacity on an annual or biennial basis and lays out clear parameters around methodology to ensure accuracy and consistency across reports. Failing that, lawmakers and taxpayers will continue to be kept in the dark as to the true scale of the Pentagon’s waste and the squandering of taxpayer dollars it entails.