In foreign policy discourse, the phrase “the national interest” gets used with an almost ubiquitous frequency, which could lead one to assume it is a strongly defined and absolute term.

Most debates, particularly around changing course in diplomatic strategy or advocating for or against some kind of economic or military intervention, invoke the phrase as justification for their recommended path forward.

But what is the national interest, really?

It should come as no surprise that the term is actually as contestable as any other social science label. Different people will approach the question with perspectives that vary based on factors as different as what region they originate from or what their concept of the national government is. A person of a more conservative disposition might see it as ensuring the protection of a culture from outside influence, while a leftist could see it as one defined by class interests, with the National Interest itself being both defined and controlled by the ruling class of a given society for their own internal as well as external self-interest.

The liberal center, meanwhile, clearly sees it as a method to spread global markets and values.

In realism, the political philosophy that sees foreign affairs as effectively the art of seeking the practical path to survival and thriving in an anarchic world with a minimum of ideological attachments, the concept of a national interest is left almost intentionally vague — a recognition of the fact that domestic and international politics are two different fields that often diverge from society to society. This, however, does not mean that the concept should not be explored, especially for those in the United States and its allied nations who value a more restrained approach to the world after decades of ruinous interventionism.

In “The National Interest: Politics After Globalization”, University College London associated professor and author Philip Cunliffe argues that the very ambiguity of the concept is itself a strength. Drawing from the historical evolution of the kind of raison d’etat first popularized by figures like Machiavelli and Cardinal Richelieu, Cunliffe argues that the French Revolution and other events in the enlightenment, such as the various wars of independence in the Americas, saw a turn toward making the very concept of national interest a site of popular contestation.

Rather than state that this meant a singular solid conception of the term, Cunliffe contends that this very ambiguity is the key to restoring citizen control over sovereignty from an out of touch global elite. The nation itself determines what is the national interest by openly and publicly grappling with how best to pursue communal self-interest.

Not only is this process democratic and inclusive, it also understands the limits of human knowledge and capabilities. Quoting the famous Cold War era policy planner George Kennan favorably that “Modesty to admit our own national interest is all we are really capable of knowing or understanding,” Cunliffe makes the case that, rather than a pure exercise in selfishness, upholding National Interest is a humble exercise of a community collectively attempting to navigate an anarchic world with no overarching authority to appeal to.

By appealing to a set of issues that can be understood by the average citizen and centered around their local contexts, discussions on foreign policy can be accessible to the people of a society and not merely the plaything of a ruling elite that has become more divorced from being rooted in a specific place over the course of the era of post-Cold War globalization.

The loss of regional distinctions in conceptions of interest was not just due to technological change, but a specific ideological fad among many of the policymaking classes who were too eager to embrace a borderless future. To quote Cunliffe directly:

“All distributional conflicts would be happily away by the global tide of economic growth, and politics could finally be replaced by the promulgation of ethics, law and technical expertise. Globalization solved the conundrum of the national interest because as it turned out, our national interest was in fact the same as everyone else’s: global growth and integration. Therefore liberals could claim that citizen’s interests were being met without ever having to articulate a distinct national interest, without ever having to account for how such interests were generated, where they originated, or how they were served.”

What this supposed march of progress actually did was to remove the communal aspects of foreign policy discussion from the society-at-large, and concentrate its definition even more in the hands of a small and cosmopolitan-yet-intellectually provincial elite.

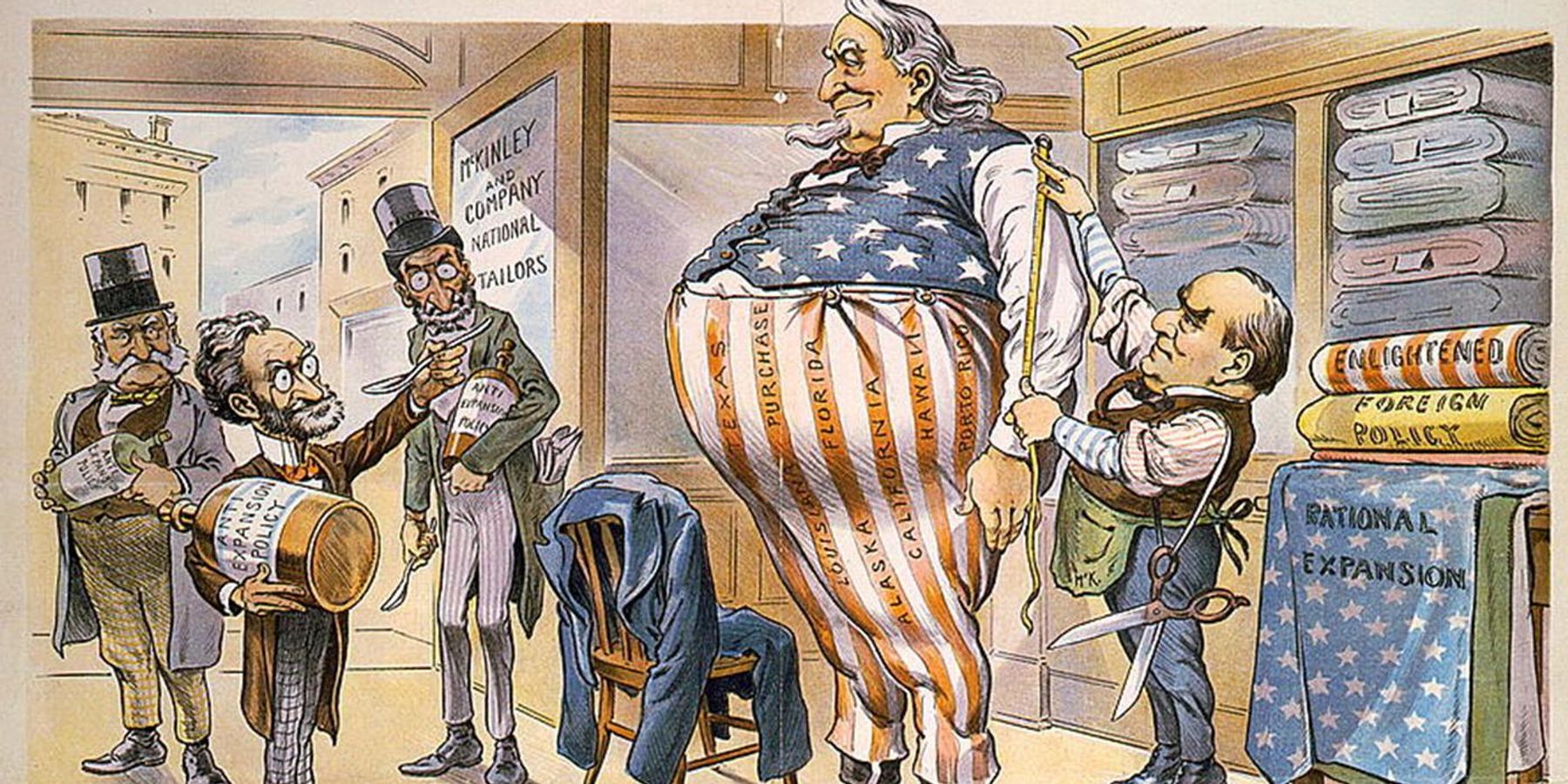

This led to a series of conflicts justified under the rubric of universal values or battling abstract concepts that had no set point of victory or defeat — which meant they could effectively drag out forever, at great lingering cost to the average person. In the United States, this trend would see the interests of the state conflated with that of the entirety of humanity itself, with the nation’s foreign policy classes seeing the fate of the species’ evolution as intrinsically tied to the ability of the Washington Consensus to export political, social, and economic norms abroad.

Meanwhile, the country selling itself as this fountainhead of progress was leaving more and more of its people behind as deindustrialization and withering investment in public infrastructure became part of the price of pursuing the project of financial and ideological globalization.

Other nations, particularly in Europe, have gone along with this in order to avoid having their own difficult discussions on their subordinate positions in the American-led order. To be junior partners in a grand project of humanitarian uplift is a more flattering self-conception than to simply be a satrapy of a global protection racket, after all.

But with Denmark being overtly threatened by a change in U.S. approach to the world, even after dutifully serving its NATO obligations in Afghanistan after 9/11, frank discussions on the national interest seem poised to make a comeback even in countries long accustomed to U.S. predominance.

By returning to locality and discussion within specific communities rather than bland universalism, the national interest becomes, in Cunliffe’s terms, something that breaks the monopoly of unelected bureaucracy and thus something that will “not lie” like the pleasing bromides of ideology when it comes to grappling with an uncertain future. Not because it contains certainty, but because it is ambiguous and must be contested out in the open by the general public in order to determine what it should be.

- Philosopher saints Augustine, Aquinas guide US grand strategy ›

- Britain's half-baked national security strategy ›